Signer #7, Margaret Schooley: "The Fingerprint"

Signer #7, Margaret Prall Shotwell Schooley

Born: December 27, 1806, Woodbridge, New Jersey

Died: 1900, Linadale, Florida, age 93

Occupations: Boarding House Keeper, “Keeping House”

Local Residences: Whisky Hill Road, Waterloo, 59 Elizabeth Street, Waterloo

Your name, most likely, does not make you unique. There are, very probably, other individuals, both living and dead, whose given name and surname are identical to yours. Such namesakes might even be roughly the same age as you. They might even live nearby.

Your family unit, on the other hand—with the distinctive names, ages, and places of birth belonging to each individual—is astronomically unique. I would be hard pressed to find a household (other than yours) that contains a group of people who happen to share all of your family members’ exact names, who are the same age, and who were born in the same place, respectively. You might have many name doppelgängers somewhere out there in the world, but you very likely don’t have any family doppelgängers.

After leaving Waterloo in the 1860s, Margaret Schooley, Signer #7, traveled with a distinct family unit that makes tracing her lifelines possible. Like many Declaration signers, she would light out West for the territories in the decades after the Convention. And once in these borderlands, the Schooleys would move erratically and often.

An unusual feature of Margaret Schooley’s story, however, is that she would live out her final years in Florida. This improbable relocation back east, to the Deep South, is unlike any other signer profiled so far. Without the clear fingerprint of her family unit to map out her life, Signer #7’s archival blips in such disparate geographical locations would likely evade detection. These movements late in her life are daunting even by modern standards. The search for Signer #7 was greatly assisted by family trees, constructed by descendants and posted in Ancestry.com, which provided a large number of biographical leads. In addition to a sketch of Margaret Schooley's life, I will also detail the records (I could uncover) of the children in her rather large, blended family.

Signer #7 was born Margaret Freeman Prall in Woodbridge, New Jersey, on December 27, 1806, the daughter of one Isaac Prall (Shotwell 177). In November 1824, she married David Shotwell. Margaret and David would have five children: Mary, William, Josephine, and two daughters who died in infancy (Myers 220).

David Shotwell would come to an untimely end in 1836. According to Ambrose Shotwell’s 1897 Quaker genealogy, Annals of Our Colonial Ancestors, David “dw.,” which I interpret to mean drowned, “on the shore of Staten Island Sound, at the steamboat landing, called Red Bank…about one mile from the town of Woodbridge” (177).

After her first husband's death, Margaret married Azaliah Schooley (Signer #100), on August 28, 1838, in Middlesex, New Jersey (New Jersey Marriage Records). The widowed newlyweds would take up residence at Azaliah’s homestead in Waterloo, joining two sons from his previous marriage, Samuel and Levi. An 1850 map of Waterloo situates the Schooley farm on a tract north of the village (Weber 178). The New York State Suffrage  Waterloo Map, 1850Trail online places this residence on modern-day Whiskey Hill Road.

Waterloo Map, 1850Trail online places this residence on modern-day Whiskey Hill Road.

By all appearances, Margaret shared her husband’s Quaker faith and the diverse radicalisms that came with it. Like many signers, the first piece of evidence regarding Margaret’s presence in the Finger Lakes Region is the 1848 Declaration of Sentiments. Margaret’s and Azaliah’s signatures are ninety-two spaces apart in the Declaration, likely making them the furthest-separated signatures among immediate family members in the document.

The year after the Seneca Falls Convention, the couple would attend the Yearly Meeting of Congregational Friends, which took place in Waterloo on June 4 through 6, 1849. The Congregational Friends had branched off from the Hicksite Quakers in 1848 because of their more trenchant position on matters related to abolition (Thomas 28). Presumably held at the meeting house on Ninefoot Road, the gathering was a virtual reunion of the Seneca Falls Convention: Margaret Pryor (#3), Mary Ann M’Clintock (#6), Rhoda Palmer DeGarmo (#48), Susan Doty (#53), Richard P. Hunt (#69), William G. Barker (#77), Elias Doty (#78), William S. Dell (#80), and Thomas M’Clintock (#86) were present and were recorded participating in the meeting deliberations (Proceedings 3-5, 13). Margaret and Azaliah were appointed to positions in the group’s correspondence and publication committees; Azaliah was elected treasurer (3, 9). In its published platform, the Congregational Friends stand firmly opposed to the ills of priestcraft, war, intemperance, slavery, racial prejudice, and capital punishment. “The Rights and Wrongs of Woman” were also key topics considered and discussed (4).

The Schooleys then appear in an 1850 census record taken by Isaac Fuller. Margaret, 42, and Azaliah, 43, live with Margaret's daughter Josephine, 17. Samuel, 21, and Levi Schooley, 14, are the sons of Azaliah and his first wife, Mercy Lundy Schooley, who died the same year that Levi was born. Isaac Preble, 10, and Margaret/Maggie, 7, are the children of Azaliah and Margaret (Myers 220).

Azaliah died of consumption on October 24, 1855, and he is interred at the Ninefoot Road cemetery. In spite of her second husband’s death, Margaret would remain active in the Congregational Friends. Renamed the Friends of Human Progress in the 1850s, the group held its annual meeting in Waterloo on June 3 through 5, 1859. Margaret and Stephen Shear (possibly Signer #98) are designated as members of the committee to plan a subsequent annual meeting (Proceedings 15). Other Declaration signers present included Amy Post (#10), who was appointed secretary, and Frederick Douglass (#73), who gave two extended orations on slavery and religion. At this meeting, the Friends of Human Progress actively debated whether the evil of women’s slavery was greater than or equal to that of chattel slavery in the South (7). The group adopted a platform decrying sectarianism, chastising American Christianity for its failure to combat slavery, and demanding the equal rights of women.

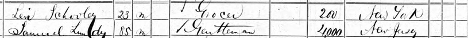

The 1860 census identifies Margaret as a “boarding house keeper,” who operates an establishment in Waterloo. In Brigham’s 1862 directory, “Mrs. Margaret Schooley” keeps home at “59 Elizabeth” Street in Waterloo's town center (42). It might be speculated that Azaliah’s death and financial necessity had forced the family to move here from their farm on the outskirts of town. The census values Margaret’s worth in real estate at $5,000 and her personal assets at $200.

Maggie, 17, and Levi, 23, a grocer, live in the household. Samuel Lundy, 85 and a “Gentleman,” is most likely Mercy Lundy Schooley’s father and Azaliah's father-in-law.

By this time, Margaret’s daughter Josephine had married Henry Welles, a druggist. In 1860, Josephine and Henry live in Waterloo with two children, Hadley and Helen, who would both die in the 1860s. I would be remiss if I did not mention that, in a truly strange twist of American history, Henry Welles would be inaccurately credited with inventing the Memorial Day holiday, over a century after his death. In the 1960s, the Johnson Administration and Congress sanctioned a narrative that Welles had suggested the creation of the holiday to honor the Civil War's dead, thereby spuriously designating Waterloo as the official birthplace of Memorial Day. The reality is that Henry Welles is said to have died months after celebrating Memorial Day in 1868. How his demise was associated with observing the holiday is unclear, but he was nevertheless posthumously swept up into Memorial Day’s origin mythology long after his passing (Croyle “Origin”). He is interred next to Hadley and Helen in Maple Grove Cemetery in Waterloo (“David Welles”).

Margaret’s and Azaliah’s son Isaac, now 20, appears in the 1860 census in Davenport, Iowa, residing in the household of Levi Lundy, likely an extended-family relation. Despite his Quaker upbringing, Isaac would enlist in the 66th Illinois Infantry, later the 14th Missouri Infantry, at the outset of the Civil War. Based upon his draft registration record and pension application, Isaac served as a “Berdans Sharp Shooter,” though this could possibly indicate a Birge’s or Western Sharpshooter, the military outfit that essentially pioneered the combat role of the long-range sniper. Isaac was discharged for some unspecified disability near Corinth, Mississippi, in 1862 or 1864 (Illinois Civil War Muster).

Illinois Draft Registration Entry for Isaac P. Schooley Levi Schooley would serve in the 53rd Illinois Infantry, entering service in December 1861 and mustered out for a disability in June 1862 (Pension Index, Illinois Civil War Muster). Levi and Isaac both married shortly after the close of the war. Levi wed Mary F. Cromwell in May 1865 in Ontario, Canada (the province of his father’s birth). Isaac married Elma Stevenson in Utica, Illinois, in January 1867 (Stevenson 130).

Illinois Draft Registration Entry for Isaac P. Schooley Levi Schooley would serve in the 53rd Illinois Infantry, entering service in December 1861 and mustered out for a disability in June 1862 (Pension Index, Illinois Civil War Muster). Levi and Isaac both married shortly after the close of the war. Levi wed Mary F. Cromwell in May 1865 in Ontario, Canada (the province of his father’s birth). Isaac married Elma Stevenson in Utica, Illinois, in January 1867 (Stevenson 130).

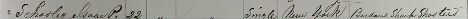

By the 1870 census, Margaret Schooley surfaces in the 5th Ward of Chicago, more than 620 miles away from Waterloo.

Margaret resides with Elma and Isaac, a grocer. Mary and Levi, also a grocer, reside in Chicago by 1870 as well. They have two children, George and Arthur.

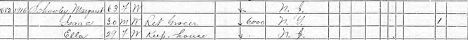

By the 1880 census, Margaret Schooley and her family have relocated, again, to Darlington, Wisconsin, 150 miles distant from Chicago. Josephine Welles has joined Margaret, Isaac, and Ella.

The 1885 state census conducted in Arkansas City, Kansas, records druggist “I P Schooley,” “Ella,” Josephine Welles, and Margaret Schooley, now 78. Arkansas City is over 650 miles away from Darlington, Wisconsin.

The same set of individuals appears in the June 1900 census, living in Linadale, Florida, a location over 1200 miles removed from Arkansas City.

Margaret’s age in this record is prematurely listed as 95, and her place of nativity is given incorrectly as New York State. Whatever motivated the Schooleys to move about so much in the West and finally settle in Florida remains unknown. The horseshoe-shaped sojourn from Waterloo to Chicago to Darlington to Arkansas City to Linadale comprises a formidable distance of more than 2,600 miles, a journey completed before the mass production of the automobile or the advent of commercial aviation.

A family headstone in Linadale marks the death of Signer #7, Margaret Schooley, some time after June in 1900, aged 93. Her son Isaac would pass away in 1902. Elma and Josephine would live together in Linadale by the time of the 1910 census. Josephine Shotwell Welles would pass away in 1921. Elma Schooley would live to 1935.

Azaliah’s son Levi and his wife, Mary, moved to Kansas before relocating back to Chicago. Levi died in late December 1891 (Illinois Death Index).

Azaliah and Margaret’s daughter, Maggie, married Joseph Bonton Crosby in Waterloo in February 1863 (Presbyterian Church). In the 1870 census for New York City, Joseph works as a collector, and Maggie "keeps house." Samuel Schooley, Azaliah’s eldest son, resides with them, working as a butcher.

Samuel married one Josephine Williams in 1873 (Episcopal Diocese). Samuel works for the Meat Commission in the 1905 New York State census. He would pass away in Manhattan in April 1910 (New York Death Index).

Maggie and Joseph appear living in London in 1891, in the Parish of St. George’s Bloomsbury, with a son, Guy. Joseph and Guy have found work in the United Kingdom as financial brokers. Maggie would pass away in Manhattan in 1907 and is interred in Maple Grove Cemetery in Waterloo.

Notwithstanding marriages, deaths, and long-distance migrations, again and again, the members of Margaret’s and Azaliah’s blended family appear to rely on each other. They would move and live in tandem. Still, the reason why Margaret Schooley moved so much across the American landscape with her son and daughter is something of a mystery.

Works Cited

Armstrong, William C. The Lundy Family and Their Descendants of Whatsoever Surname. M.A. Berry, 1902.

“Azaliah Schooley-Margaret Shotwell Marriage.” New Jersey Marriage Records, 1670-1965. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020

“Azaliah Schooley Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Waterloo, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Azaliah Schooley House.” New York State Women’s Suffrage Trail. https://wranys.org/trailsite.php?tid=307. Accessed 11 Aug. 2020.

Brigham, DeLancey. Brigham’s Geneva, Seneca Falls, and Waterloo Directory and Business Advertiser, For 1862 and 1863. 1862.

Croyle, Jonathan. “The Origin of Memorial Day: Is Waterloo’s Claim to Fame the Result of a Simple Newspaper Typo?” Syracuse.com 24 May 2019, https://www.syracuse.com/living/2019/05/the-origin-of-memorial-day-is-waterloos-claim-to-fame-the-result-of-a-simple-newspaper-typo.html. Accessed 11 Aug. 2020.

“Ella Schooley Household.” Federal Census, 1910. Linadale, Marion County, Florida. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Henry Welles Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Waterloo, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Henry Welles.” Findagrave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/162225541/henry-carter-welles. Accessed 11 Aug. 2020.

“I. P. Schooley Household.” Kansas State Census, 1885. Arkansas City, Kansas. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Isaac Schooley.” U.S. Civil War Draft Registrations Records, 1863-1865. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Isaac Schooley.” US Civil War Pension Index: General Index, 1861-1934. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Isaac Schooley.” Illinois Civil War Muster and Descriptive Rolls Database. https://www.ilsos.gov/isaveterans/civilMusterSearch.do?key=2102. Accessed 12 Aug. 2020.

“Isaac Schooley Household.” Federal Census, 1900. Linadale, Florida. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“J.B. Crosby Household.” Federal Census, 1870. New York, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Joseph Crosby Household.” United Kingdom Census, 1891. London, England. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Josephine Welles Household.” Federal Census, 1880. Darlington, Wisconsin. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Levi Schooley.” US Civil War Pension Index: General Index, 1861-1934. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Levi Schooley.” llinois Civil War Muster and Descriptive Rolls Database. https://www.ilsos.gov/isaveterans/civilMusterSearch.do?key=2102. Accessed 12 Aug. 2020.

“Levi Schooley-Mary Cromwell Marriage.” Ontario, Canada, County Marriage Registers, 1858-1869. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Levi Schooley.” US Civil War Pension Index: General Index, 1861-1934. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Levi Schooley Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Chicago, Illinois. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Levi Schooley Death.” Cook County, Illinois Death Index, 1878-1922. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Margaret Crosby.” Findagrave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/194170461/margaret-p_-crosby. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020

“Margaret Schooley Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Waterloo, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Margaret Schooley Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Chicago, Illinois. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Margaret Schooley.” Findagrave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/82344345. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Margaret Schooley-Joseph Bonton Crosby Marriage.” U.S., Presbyterian Church Records, 1701-1907, Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

Myers, Patty Barthell. Ancestors and Descendants of Lewis Ross Freeman with Related Families. Penobscot Press, 1995.

Proceedings of the Yearly Meeting of Congregational Friends, Held at Waterloo, N.Y. Oliphant’s Press, 1849.

Proceedings of the Yearly Meeting of Friends of Human Progress, Held at Waterloo, Seneca Co. N.Y. Hebard & Co., 1859.

“Samuel Lundy Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Davenport, Iowa. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Samuel Schooley-Josephine Williams Marriage.” The Episcopal Diocese of New York, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Samuel Schooley Household.” New York State Census, 1905. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

“Samuel Schooley Death.” New York, New York, Extracted Death Index, 1862-1948. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

Shotwell, Ambrose Milton. Annals of Our Colonial Ancestors and Their Descendants; or, Our Quaker Forefathers and Their Posterity. R. Smith & co, 1897.

Stevenson, John R. Thomas Stevenson of London, England and His Descendants. H. E. Deats, 1902.

Thomas, Allen. “Congregational or Progressive Friends: A Forgotten Episode in Quaker History.” Bulletin of Friends' Historical Society of Philadelphia, vol. 10, no. 1, 1920, pp. 21-32.

Weber, Sandra. Special History Study, Women’s Rights National Historical Park, Seneca Falls, New York. National Park Service, 1985.