Signer #39: Dorothy Mathews, "The Physician"

Best Candidate: Signer #39, Dorothy B. Dewey Mathews

Born: Circa 1804, Connecticut

Died: July 22, 1875, Tyre, Seneca County, Age 71

Occupation: Physician

Local Residences: Magee’s Corners, Tyre, Seneca County

Thanks to Annie Anderson for research assistance provided for this profile.

One detail stands out about the best candidate for Signer #39. After the death of her spouse in 1857, Dorothy Dewey Mathews of Tyre lists her profession as "Physician" in the 1860 and 1870 censuses. She appears to have made a comfortable living at this trade, working as a doctor when women’s professional opportunities were overwhelmingly restricted to non- or low-paying menial labor. The women listed in 19th-century records as “tailoress,” “seamstress,” or “keeping house” are too numerous to count.

But what did Dorothy Mathews mean when she identified herself as a physician to the census-taker? Could she have served in the capacity of a community midwife or nurse? To answer this question, I reached out to Annie Anderson, the curator of The Country Doctor Museum in Bailey, North Carolina. Ms. Anderson replied: “From my understanding of medical history, if this woman listed her profession as ‘physician,’ I believe she was most likely a doctor in the typical sense of the word. Had she been a midwife, she probably would have listed that term or ‘nurse.’ Physicians in the 19th century believed themselves to be part of a scientific profession and I think the term would have been used with purpose.”

I had no luck searching for records of Dorothy Mathews’ enrollment in then-existing medical schools for women. And she would have worked as a physician when the field of medicine was not the strictly regulated profession we know today, with its exacting standards for licensure and accreditation. To be a doctor in the 19th century, you did not need formal schooling. The profession more closely resembled a trade, where one could begin practicing medicine after an apprenticeship or some other in-kind work experience. This would have been especially true in a rural area like the hamlet of Tyre.

It is becoming evident that creating pathways for women’s formal engagement in medical science was a veritable obsession among the signers of the Declaration of Sentiments and their families. Signer #1, Lucretia Mott, was a founder of Philadelphia's Female Medical College of Pennsylvania (FMCP), only the second institution in the world to offer women an MD. Her spouse, James Mott, Signer #81, would later serve on its board of trustees. Rebecca M.C. Capron, the spouse of Signer #96, E.W. Capron, attended FMCP between 1853 and 1855. In adulthood, Charlotte Woodward, Signer #37, and her spouse, Cyrus Newlin Peirce, served as officers on the board of WMCP and its service apparatus, the Woman's Hospital of Pennsylvania.

Moreover, at the same time as the Convention, Elizabeth Blackwell was in the process of becoming the first woman to earn a medical degree in the United States. She did so at the Geneva College Medical School (GCMS), just a short distance west of Seneca Falls. Weathering a slew of rejections from institutions in New York City and Philadelphia, Blackwell was admitted to GCMS after the school’s male student body unanimously voted to allow her in. Blackwell reports in an 1895 autobiography that they might have done so ironically, acting upon a suspicion that news of her matriculation was “a hoax, perpetrated at their expense by a rival college” (73). Blackwell began at GCMS in November 1847 and spent the next 14 months working toward her medical degree, even as taboos forbidding women’s exposure to the bloody inner-workings of the human body barred her from courses on surgery and human anatomy. Beyond her own activism, Blackwell’s familial links to the Suffrage Movement are extensive. Her brother Henry Brown Blackwell married AWSA leader Lucy Stone. Her other brother Samuel Charles Blackwell married Antoinette Brown Blackwell, the first ordained woman minister in the U.S., a feminist evolutionary theorist, and AWSA leader. Early suffragists appear to have been keenly aware of the obvious public health benefits behind training women as doctors—and its political stakes.

But is Dorothy Dewey Mathews of Tyre, in fact, Signer #39? In the 1850 census for Seneca County, there are two individuals named “Dorothy Mathews.” They both reside in Tyre, which is a short distance due north of Seneca Falls. One Dorothy Mathews, the daughter of farmer N.P. Mathews, is 14 years old by the time of the 1850 census. This means she would have been 12 in 1848. This Dorothy Mathews is two years younger than the youngest known signer, Susan Quinn, Signer #33 (Wellman 205, Clinton). Quinn was approximately 14 years and 6 months old at the time of the Convention ("Susan Q. Clark"). Moreover, she lived within the town limits of Seneca Falls and was well inside walking distance of the Wesleyan Chapel. Convenience made the adolescent Quinn's involvement in the Convention more logistically feasible. If 12-year-old Dorothy Mathews is Signer #39, none of her immediate family members signed the Declaration along with her.

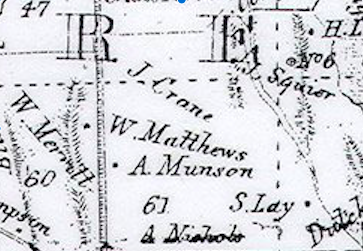

Alternatively, Dorothy's aunt and namesake, Dorothy Dewey Mathews, would have been approximately 44 years old in 1848. An 1850 map of Tyre situates the property of her husband, William, on the south end of the hamlet, located on modern-day Route 101, just north of modern-day Route 318.

If this is the Mathewses’ homestead, it sits less than 4 miles away from the Wesleyan Chapel. I am inclined to favor the elder Dorothy Mathews as the most likely candidate to be Signer #39. She would have held more authority in her home to embark on a day trip to Seneca Falls, relative to that of her 12-year-old niece. Other than these two individuals, I could find no one else named Dorothy Mathews living in the Finger Lakes Region during the 1840s, and I could find no one with that name attached to regional activist networks.

Dorothy was William Mathews' second wife, and there is some mention of his first marriage in The History and Biographical Record of Lenawee County, Michigan (1880). William and Susan Warner Mathews (William's first wife) were both “natives of New Jersey, and were pioneers of Seneca county, N.Y., having settled there with their parents when they were children. [William] was a farmer and owned a farm in Tyre, Seneca county, where he died. [Susan] died in Fayette, Seneca county, in 1832, leaving seven children” (349). According to Findagrave.com, Susan Warner Mathews is interred in Burgh Cemetery in Fayette, the same location where James Easton, the spouse of Elizabeth Conklin, Signer #30, lies in rest.

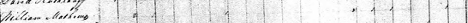

The household of William Mathews appears in Seneca County in the 1820 census:

He also is recorded in the 1830 census:

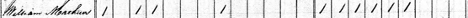

A short time after Susan's death in 1832, Dorothy married William, who was 18 years her senior. Their household appears under William's name in the 1840 census for Tyre:

A short time after Susan's death in 1832, Dorothy married William, who was 18 years her senior. Their household appears under William's name in the 1840 census for Tyre:

William, as head-of-household, resides with 3 males under the age of 20; one female in her 30s, presumably Dorothy; one female in her 20s; and 4 females under the age of 20. This history is supported by family trees constructed for William and Dorothy on Ancestry.com

The 1912 death certificate for Dorothy and William's son, Edward, confirms "Dewey" as being Dorothy's birth surname and her birthplace as Connecticut. Edward's birth in 1835 places Dorothy and William's marriage some time prior to that.

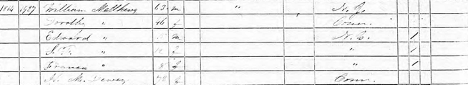

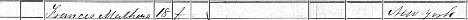

Like many signers, the first explicit record of Dorothy's presence in the Finger Lakes Region is the Declaration of Sentiments itself. Dorothy next appears in the 1850 Tyre census, in a record taken by Isaac Fuller:

Now 46, Dorothy lives with William, 63, and they have three children: Edward, 15; Susan or "S.F.," 14; and Frances, 8. In the same residence, a 78-year-old female, "H.M. Dewey," hails from Connecticut. I take H.M. Dewey to be Dorothy's mother or another elder relative.

According to a probate letter filed in Waterloo, William Mathews passed away on September 5, 1857. Recently widowed, Dorothy, 53, appears in the 1860 census for Tyre as a "Physician."

She lives with daughter Frances, now 18. She appraises her assets in real estate and personal property at a combined total of $2,100 dollars. It is difficult to assess whether William's passing enabled Dorothy to take up this profession. Perhaps economic necessity drove her to practice medicine in order to support herself and her unmarried daughter. Perhaps a growing demand for doctors, especially in the lead-up to the Civil War, enabled her to become one.

In the following census for Tyre in 1870, Dorothy is again identified as Physician:

Her wealth is again valued at $2,100. She now lives alone in her household, a rarity in a culture where elders frequently cohabitated with younger relatives. I could not locate Dorothy's home in the map of Tyre produced in 1874. Using the families listed on the same page of the 1870 census--namely the households of James Van Arsdale and Charles G. Corwin--she likely lived in the neighborhood of Magee's Corners, in Tyre's southwest quadrant.

According to family trees constructed on Ancestry.com, Dorothy’s eldest daughter, Susan, married Edmond Livingston. Susan Mathews Livingston appears in the 1870 census for Tyre, “keeping house.” The couple has four young children: William, Edmond, Grace, and Phebe. According to the same family tree, she died in Ash, Michigan, shortly thereafter, in 1872. She would have been 36.

Dorothy’s daughter Frances married James Payne. They had a child, Jessie. Frances passed away in 1876, at about 34 years old, and is interred in Spring Brook Cemetery in Seneca County.

Like many of his siblings, Edward relocated to Michigan, marrying Mary Goodell in October 1884. He appears in the 1900 census as a farmer in Allegan, Michigan. In the 1910 census, Edward appears as an inmate in the Michigan Asylum for the Insane, located in Kalamazoo. He would pass away in 1912, at age 77.

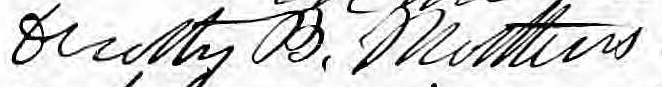

According to her probate letter, Dorothy passed away in July 1875. A handwritten transcription of her last will, presented in surrogate’s court on July 28, includes the bequest of six “silver tea spoons” to her granddaughter. Dorothy outlived her daughter Susan and would be survived by her daughter Frances by only one year. Her son Edward lived to old age but spent his final years in an insane asylum.

The transcription of Dorothy B. Matthews signature from her will.

Two separate census records mark Dorothy B. Mathews working as a physician. This suggests that she had garnered enough standing and respect in her community to be acknowledged as such by the census. Both of her daughters died in early adulthood. Her son spent his final days in an insane asylum. It is clear that the medical profession, in that day, stood to benefit from the inclusion of competent healthcare professionals, regardless of sex. The type of medicine Dorothy Mathews practiced is unknown. The records of her life are scant. But it must have taken a great deal of determination for her to be physician and serve her community when she did.

Works Cited

Blackwell, Elizabeth. Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women. Longmans, Green, and Company, 1895.

Clinton, Hillary. “150th Anniversary of the Women’s Right Convention Seneca Falls.” Accessed 1 Mar. 2021. https://clintonwhitehouse4.archives.gov/WH/EOP/First_Lady/html/generalspeeches/1998/19980804-3206.html.

“Dorothy Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Tyre, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

“Dorothy Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Tyre, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

“Dorothy Mathews Last Will and Testament.” Seneca Falls, New York, Surrogate Court, July 28, 1875. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

“Edmond Livingston Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Tyre, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

“Edward Mathews-Mary Goodell Marriage.” Marriage Records, Secretary of the State of Michigan, Allegan, Allegan County, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

“Edward Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1900. Allegan, Allegan County, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

“Edward Mathews Death Certificate.” State of Michigan, Vital Statistics, Kalamazoo County, 10 Oct. 1912. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

“Frances Mathews Payne,” Findagrave.com. Accessed 27 Feb. 2021. Findagrave.com,https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/ 149529181/frances-l.-payne.

“N.P. Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Tyre, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

"Susan Quinn Clark. Findagrave.com. Accessed 27 Feb. 2021. "https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/170878015/susan-m.-clark.

“Susan Warner Mathews.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/104495297/susan-matthews.

“Tyre in 1850.” Maps of Seneca County & Various Town – Seneca County, New York. https://www.co.seneca.ny.us/maps-of-seneca-county-various-town/. Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

“Tyre in 1874.” Maps of Seneca County & Various Town – Seneca County, New York. https://www.co.seneca.ny.us/maps-of-seneca-county-various-town/. Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman’s Rights Convention. University of Illinois Press, 2010.

“William Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1820. Junius, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

“William Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1830. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

“William Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1840. Tyre, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

“William Mathews Probate Letter.” Waterloo, New York, 1857. New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999. Ancestry.com. Accessed 27 Feb. 2021.

Whitney, W.A. & R.I. Bonner. History and Biographical Record of Lenawee County, Michigan. W. Sterns, 1880.