Signer #71, Justin Williams: "The Local Nomad"

Born: May 1, 1813, Cairo, Greene County, New York

Died: October 17, 1878, Seneca Falls, age 65

Occupations: Spinner, Clerk, Merchant, Census Enumerator, IRS Gauger

Local Residences: 5 Ovid Street, 47 Bridge Street, Piedmont Hotel, Spring Street

“I knew it. I knew it. Born in a hotel room, and God damn it, died in a hotel room.”

—Eugene O’Neill’s last words

The son of an itinerant pastor turned traveling Bible salesman, Justin Williams spent most of his adult life in Seneca Falls, but he never did settle into a single occupation or household. Taking after his father, Signer #71 was something like a local nomad, who drifted around to multiple residences within the village. In doing so, his life intersected with one other speculative signer of the Declaration of Sentiments.

At first blush, “Justin Williams” appears to be an intimidating prospect for database searches because both his given name and surname are exceedingly common in the United States. Omnipresent as the name may be nowadays, this was not always the case. Luckily, the first name “Justin” seems to have been a relative novelty in the Finger Lakes Region during the second half of the 19th century. For instance, Brigham's 1862 directory includes only one individual, among thousands, with the given name "Justin," Justin Williams (72). There is only one “Justin Williams” living anywhere close by at the time of the Convention. What's more, I could find no other Justin Williams present in regional activist networks. As strange as it may sound to us now, there aren't a multitude of competing Justin Williamses who could be Signer #71.

The most extensive lead into the background of #71 occurs in David Dudley Field's Brief Memoirs of the Members of the Class Graduated at Yale College in September, 1802. The book is, in part, a genealogical account of this particular graduating class at Yale. Identified in the volume, the son of 1802 alumnus Richard Williams, one Justin Williams “resides at Seneca Falls” by the time of the book's publication in 1863 (56).

Justin's father, Richard Williams was born in Lebanon, Connecticut, in 1780. After finishing at Yale, he was ordained in Brookfield, Connecticut, in 1807 and married Justin’s mother, Electa White, in May 1808. In 1812, the Williams family relocated to Cairo, New York, where Justin was born in 1813, the third of Electa and Richard’s nine children. Dismissed from his ministerial appointment in 1816, Richard is said to have spent three months on a mission trip in the Catskill Mountains before returning the family back to Connecticut for three years. In September 1820, the Williamses re-migrated to New York, this time to Penn Yan, Yates County, “installed there by the Presbytery of Geneva” (54). This position was terminated in 1825 and effected subsequent moves to Fairport, Southport, Tioga County, Chenango, and Reading (55). During the 1830s, Richard distributed bibles from door to door throughout the Finger Lakes Region, including “Cayuga, Onondaga, Seneca, Ontario, Wayne, Yates, Madison, Oneida, Cortland, Chenango, Broome, and Tompkins” (55).

Field remembers that Richard Williams “was a warm friend of the New-School Presbyterian Church, and an earnest advocate of the cause of Temperance and Anti-Slavery” (55). Sadly, Richard’s final years were turbulent ones. Field remarks that “by a mysterious Providence, he had one or two fits which affected his reason so that he became insane, and was incapable of performing any kind of labor as long as he lived” (55). He passed away in Union Springs, just south of Seneca Falls on Lake Cayuga, November 15, 1844.

Justin’s mother, Electa White Williams was born in Andover, Connecticut, in February 1783. She appears in the 1850 census residing in nearby Springport with her children Elizabeth, Harriett, and Charles, a merchant. Allyn S. Kellogg’s 1860 genealogy, Memorial of Elder John White, marks Electa’s passing on March 25, 1851 (209).

Like many signers, the Declaration of Sentiments is the first record of Justin Williams’ presence in Seneca Falls. The third signatory of the men’s section, his name is located between those of Samuel D. Tillman (#70) and Elisha Foote (#72). Tillman and Foote would both be elected as village president, Foote in 1845 and Tillman in 1852 (History 110). Justin’s positional situation between two local politicians suggests that he might have had political ambitions himself—a connection that is borne out in the coming decades.

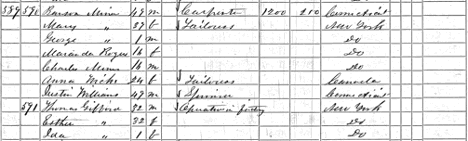

Justin appears in an 1850 census record taken by Isaac Fuller. He is one of 15 boarders in a hotel run by the Milk family. This residence is recorded in the census three household visitations away from the home of Amelia Bloomer, which still stands on East Bayard Street in the Fourth Ward. In the 1862 village directory, the eating house run by the Milks is situated on 5 Ovid Street, a stone’s throw from East Bayard (57).

In 1850, Justin is 32 years old and works as a "spinner," essentially meaning that he meshed together fibers to produce the thread used in textile production. Judith Wellman has observed that he is the only known signer to be associated with the textile industry in the 1850 census, especially because women’s occupations are not taken down by Fuller (16, 33). The question of how jobs in the textile industry might have lured women and their families to the Seneca Falls area is an important one, and it is safe to assume that the actual number of textile workers at the Convention was much greater.

By the 1860 census, Justin still works as a spinner. His age and birthplace in that year’s census are erroneously recorded as being "49" and "Connecticut," respectively. Here, Justin appears as a boarder in the home of Ransom and Mary L. Minor. I profiled Mary Minor as a possible candidate for Signer #34, “Mary S. Mirror,” where I suggest that her cursive signature was transcribed incorrectly at some point in the publication process. Since the lives of Justin Williams and Mary L. Minor overlap as tenant and landlady, I would argue that their connection strengthens the case that both individuals are the actual signatories from the Declaration. That these two former local signers are living under the same roof 12 years after the Convention also echoes a notion that the social ties represented in the Declaration lived on, well after the close of the Convention.

Minor Household, 1860 CensusThe 1862 village directory places both Ransom Minor and Justin Williams (as a boarder) at “47 Bridge” Street (57, 72).

Minor Household, 1860 CensusThe 1862 village directory places both Ransom Minor and Justin Williams (as a boarder) at “47 Bridge” Street (57, 72).

In the Memorial of Elder John White, Justin's occupation is listed as “merchant” in 1860 (106). It also reports that Justin’s siblings Charles and Harriet happen to live in Seneca Falls. Three other siblings, Caroline, Elizabeth, and Richard, have moved, together, as far afield as Santa Cruz, California (106). The 1862 directory situates little sister Harriet and her husband, Isaac Allen, right around the corner from Justin, on 80 West Bayard (33). Harriet and Isaac would shortly move to Chicago; Charles would also relocate to Santa Cruz (Field 56).

Evidently seeking some sort of career transition, Justin eventually sought political appointment. A sample ballot re-created in the 1905 publication of Seneca Falls Historical Society identifies him as a candidate on the “Freeman’s Ticket,” seeking one of the positions for “Inspectors of Election, District No. 2” (Teller 49). Charles L. Hoskins (#85) is running for the office of Overseer of the Poor on the same ticket. This 1905 reproduction fails to distinguish the election year from which the ticket is taken.

In 1866, the Seneca County Board of Supervisors lists Justin as a census enumerator, presumably for the recent 1865 state census. He has claimed expenditures of $88.00 dollars in his data-collection duties (54). In spite of this stint as a census taker, I could not locate Justin Williams himself in the 1865 state census.

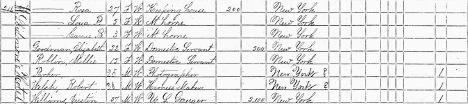

With these short-term professional experiences under his belt, Justin’s bureaucratic ambitions were more fully realized in the late 1860s. According to a U.S. Treasury Department personnel roster from 1877, Justin was appointed a IRS gauger on August 6, 1868 (210). In the 1870 census, Justin is age 57, his occupation is identified as “U.S. Gauger,” and his wealth assessed at $2,100. Denoted vertically in the column reserved for household visitations, he is counted among the boarders renting at the Piedmont Hotel.

Piedmont Hotel, 1870 Census

Piedmont Hotel, 1870 Census

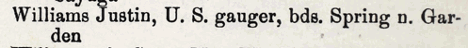

By the time of the 1874 village directory, Justin has relocated yet again. His profession remains as U.S. Gauger, but he now boards at “Spring n. Garden,” in roughly the same location as the home of signer Mary Conklin (#32) and her father, William, at roughly the same period (108).

1874 Directory

1874 Directory

So what did an IRS gauger do, exactly? In 1926, I.H. Fullmer claims that gaugers determined “the capacity of casks, in gallons, as derived from caliper measurements and use of measuring rods,” upon which “the profits of certain merchants as well as Government revenues depended” (125). I also took a gander at the Internal Revenue Service’s official manual for gaugers from 1906 to get a better sense of the profession. They were charged with monitoring the production of alcohol at breweries and distilleries in order to ensure the correct amounts of spirits had been deposited into containers, such as barrels, bottles, and kegs. They also assessed the amount to be taxed based on the manufacturer's batch production and ensured that containers were properly sealed (4-6). Gaugers were essentially the forerunners of the Alcohol Beverage Control commissions of today. Like other signers, this also means that Justin’s job as a liquor inspector depended on the continued failure of the Temperance Movement.

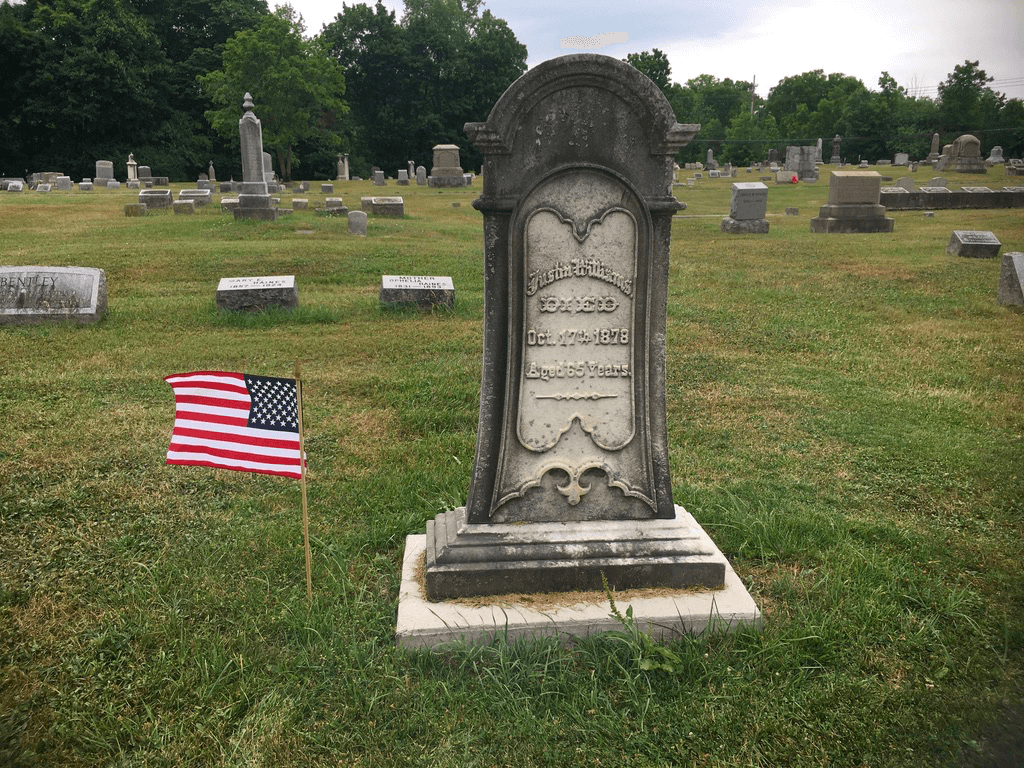

Publications from the Treasury Department and Civil Service Commission indicate that Justin remained a civil servant from 1868 to 1878 (94, 90). He passed away on October 17, 1878, at age 65. He has an ornate tombstone at Restvale Cemetery, standing on an otherwise-empty plot. The epitaph includes only his name, the date of his death, and age—as if little else was known about his life at the time of his death.

"Justin Williams DIED Oct. 17th 1878, Aged 65 Years"

"Justin Williams DIED Oct. 17th 1878, Aged 65 Years"

There are minor variations in this individual’s metrics over the decades of his life. His occupation, his recorded age, birthplace, and (especially) his place of residence change here and there. Those fluctuations nevertheless remain within margins of error that, I would argue, consistently represent the lifetime of a single individual. The avocation of spinner was gradually going extinct as the Industrial Revolution groaned on in Upstate New York. Given the march of progress, it makes sense that Justin Williams was compelled to seek low-level public office and pursue a second career as a bureaucrat, which probably also happened to pay better.

Justin Williams never settled down. He bounced from boarding house to boarding house. He dabbled, shifting careers often. What must have been a nomadic childhood gave way to a semi-itinerant adulthood. He still made Seneca Falls his home.

Works Cited

Brigham, DeLancey. Brigham’s Geneva, Seneca Falls, and Waterloo Directory and Business Advertiser, For 1862 and 1863. 1862.

Evans, William & Wesley Crofoot. Seneca Falls & Waterloo Village Directory, 1874-5. Truair, Smith & Co.

“David Milk Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 July 2020.

“Electa Williams Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Springport, Cayuga County, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 July 2020.

Field, David Dudley. Brief Memoirs of the Members of the Class Graduated at Yale College in September, 1802. Self-published, 1863.

Fullmer, I.H. “Gages and Gauging.” Weights and Measures National Conference of Representatives from Various States Held at the Bureau of Standards. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1926, pp. 125-30.

“Justin Williams.” Findagrave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/134790338. Accessed 7 July 2020.

Kellogg, Allyn Stanley. Memorials of Elder John White. Higginson Book Company, 1860.

History of Seneca Co., New York. Everts, Ensign & Everts, 1876.

“Piedmont Hotel.” Federal Census, 1870. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 July 2020.

“Ransom Minor Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 July 2020.

Seneca County Board of Supervisors. The Proceedings of the Board of Supervisors of Seneca County. Seneca County Board of Supervisors, 1866.

Teller, Fred. “Union Hall, Daniels Hall, Daniels Opera House and Other Amusement Halls of Seneca Falls.” Papers Read Before the Seneca Falls Historical Society For the Year 1905. Seneca Falls Historical Society, 1905, pp. 35-64.

U.S. Civil Service Commission. Official Register of the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1878.

U.S. Internal Revenue Service. Extracts from the Gauger’s Manual, Gaugers’ Weighing Manual, and Regulations No. 7, Revised: Regarding Duties of United States Internal-Revenue Gaugers, Storekeepers, and Storekeeper Gaugers. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1906.

U.S. Register of the Treasury. The United States Treasury Register, Containing a List of Person Employed in the Treasury Department. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1877.

Wellman, Judith. “The Seneca Falls Women's Rights Convention: A Study of Social Networks.” Journal of Women's History, vol. 3, no. 1, 1991, pp. 9-37.