Signer #5, Eunice Newton Foote: “The Climate Scientist”

Born: July 17, 1819, Goshen, Connecticut

Died: September 30, 1888, Lenox, Massachusetts, Age 69

Occupations: Painter, Scientist, Inventor

Local Residence: North Park Street, Seneca Falls  Uniquely among the signers of the Declaration of Sentiments, Eunice Newton Foote, Signer #5, has enjoyed a popular renaissance in only the past decade. This is because, in the 1850s, Foote conducted an experiment in Seneca Falls that captured the connection between the concentration of carbon dioxide in the air and climatic temperature change. This is to say that she was the first person to uncover the root phenomenon behind global warming. Profiles celebrating Foote for this achievement have since been published in Time, American History, Smithsonian Magazine, and The New York Times, with many marking the 200th anniversary of her birth in 2019. Capitalizing on renewed interest in Foote's life, Sotheby's recently sold at auction an original 1856 copy of Foote’s essay "Circumstances Affecting the Heat of the Sun's Rays," which fetched a price of $4,750.

Uniquely among the signers of the Declaration of Sentiments, Eunice Newton Foote, Signer #5, has enjoyed a popular renaissance in only the past decade. This is because, in the 1850s, Foote conducted an experiment in Seneca Falls that captured the connection between the concentration of carbon dioxide in the air and climatic temperature change. This is to say that she was the first person to uncover the root phenomenon behind global warming. Profiles celebrating Foote for this achievement have since been published in Time, American History, Smithsonian Magazine, and The New York Times, with many marking the 200th anniversary of her birth in 2019. Capitalizing on renewed interest in Foote's life, Sotheby's recently sold at auction an original 1856 copy of Foote’s essay "Circumstances Affecting the Heat of the Sun's Rays," which fetched a price of $4,750.

The importance of Foote's findings was first recognized in modernity in American Women in Science Before the Civil War (1992) by Dr. Elizabeth Wagner Reed, a geneticist and drosophila specialist. Two decades later, on a much hotter planet, researcher Ray Sorenson independently re-rediscovered descriptions of Foote's experiments, crediting her with the seminal determination that “even modest increases in the concentration of CO2 could result in significant atmospheric warming” (1). In her lifetime, it was speculated that Eunice Newton Foote’s insights into the nature of atmospheric CO2 emissions could reveal much about Earth’s geologic past. No one was then prepared to entertain questions of how her work might also speak to the planet’s future. Beyond this pivotal discovery, Foote’s life was one of robust intellectual ambition and exploration, and she leaves behind a considerable archival footprint.

Section, 1862 Passport Application

Section, 1862 Passport Application

In a handwritten passport application for her daughter and herself from July 1862, Eunice Foote attests that she was born in Goshen, Connecticut, “on or about 17th day of July 1819.” Ermina Newton Leonard’s 1915 genealogy of the Newton family identifies Eunice as the daughter of one Isaac Newton, Jr., a farmer (719). And the 1888 Massachusetts Death Index names Eunice's mother as “Theresa,” which is elsewhere rendered in present-day sources as “Thirza” (Richardson, Schwartz). The eleventh of twelve children, Eunice “was a fine portrait and landscape painter," Leonard claims, and "she was an inventive genius, and a person of unusual beauty” (720).

Sometime after 1820, the Newtons migrated from Connecticut to East Bloomfield, New York, 35 miles west of Seneca Falls in Ontario County. As a teenager, Eunice Newton attended the Troy Female Seminary (now the Emma Willard School) from 1836 to 1838 (Coakley). Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Signer #4, whose signature immediately precedes Foote's in the Declaration, attended the same institution, graduating in 1832. While the town of Troy is about 50 miles away from Stanton’s birthplace in Johnstown, it is over 215 miles removed from East Bloomfield, a formidable distance by 19th-century standards. That an eleventh-born farmer's daughter was afforded an education so far away from home speaks to the intellectual promise that Eunice Newton must have shown from an early age. Present-day sources claim that she received additional instruction at Rensselaer School (now Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute), also located in Troy—although I have not yet independently verified this in any primary source (Hecht, Richardson).

According to the 1897 National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Eunice Newton married Elisha Foote (#72) on August 12, 1841, in East Bloomfield (488). The couple eventually settled in Seneca Falls and had two children there: Mary, “born at Seneca Falls in the state of New York on the 21st day of July 1842” and Augusta, born on October 24, 1844 (Passport Application, Marquis and Leonard 39). An elder sister of Eunice’s named Althea, born in 1803, also resided in Seneca Falls, dying there in 1848 (Leonard 720).

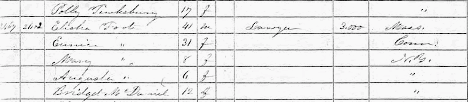

Determining the exact address of the Footes’ residence in Seneca Falls is difficult because they moved away prior to the publication of DeLancey Brigham's 1862 village directory. Moreover, they do not appear on either of the village maps produced in the 1850s. The New York State Women’s History website situates their home at North Park Street, a rough location confirmed in the 1850 census. In records taken by Isaac Fuller, the Foote home appears three household visitations prior to that of Henry Seymour (#75). Polly Tewksbury, the inferred relative of Betsey Tewksbury (#47), appears just before the Footes, living in the household of hat maker Crandall Kenyon. The 1862 directory later places the “Kinyon” household at “81 Fall” and the Henry Seymour household at “19 Cayuga,” both addresses in the northeast corner of town, in the vicinity of Park Street (52, 65). The household of Henry Powis, a neighbor of the Footes in the 1850 census, is also shown in the same general area in the 1852 map.  Curiously, Elisha Foote had, around this time, come to own the residence known today as the Elizabeth Cady Stanton House, the home that the Stanton family would eventually come to occupy in 1847. Elisha purchased it in March 1844, with the involvement of Stanton’s father, Daniel Cady, but the Footes apparently opted not to live at the Fourth Ward address (Yocum 15).

Curiously, Elisha Foote had, around this time, come to own the residence known today as the Elizabeth Cady Stanton House, the home that the Stanton family would eventually come to occupy in 1847. Elisha purchased it in March 1844, with the involvement of Stanton’s father, Daniel Cady, but the Footes apparently opted not to live at the Fourth Ward address (Yocum 15).

In 1850, Elisha, 41, and Eunice, 31, live with Mary, 8, and Augusta, 6. One Bridget McDaniel, 12 and a New York native, resides with the Footes. It is likely that McDaniel was absorbed into the Foote household from a distressed family within the community, as Polly Tewksbury had been. Elisha’s occupation is listed here as a lawyer, and the household wealth is assessed at $3,000 dollars.

With a number of biographical ties to Stanton, Eunice Foote had apparently entered into a trusted circle by the time of the Seneca Falls Convention, which happened to coincide with her 29th birthday. John Dick’s Report of the Women's Rights Convention identifies her as one of a committee of five individuals charged with preparing records of the convention proceedings, for the sake of future publication (12). The committee otherwise consisted of Mary Ann M’Clintock (#6), Amy Post (#10), Elizabeth W. M’Clintock (#16), and Stanton herself.

Another ephemeral piece of evidence illustrating Eunice's engagement in village civic life in the 1840s is her inclusion in an 1847 membership roster for the American Art Union, an organization dedicated to procuring art objects for museums. A list of subscribers in Seneca Falls includes “Mrs. Elisha Foote,” who is named immediately after “John P. Cowing,” the entrepreneur who had partnered with both Henry Seymour and Henry William Seymour (#74) in pump-making ventures during the 1840s.

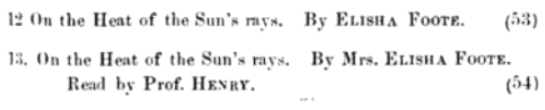

Eunice Foote’s connections, however tangential, to Seneca Falls’ embryonic pumpmaking industry would factor into her personal forays into the arena of science. On Wednesday, August 20, 1856, her work would be showcased at the Tenth Meeting of the American Association of the Advancement of Science (AAAS) convened in Albany. Individual panels were held in the State Capitol building, with notables like Henry Rowe Schoolcraft and Lieutenant Matthew Fontaine Maury slated to present (2, 4). The session for Friday, August 22, held in the Capitol Senate Chamber, schedules a talk by Elisha, “On the Heat of the Sun’s rays” (8-9). A paper composed by “Mrs. Elisha Foote,” bearing the same title, would be read by a proxy, Professor Joseph Henry, a native of Albany.

1856 AAAS Conference Program

1856 AAAS Conference Program

Professor Henry was, by then, an elder statesman of the American sciences, who had made key contributions to the study of electricity and had helped to found the Smithsonian Institution. He is said to have prefaced his recitation of Eunice's work with “a few words,” arguing that "science was of no country and of no sex" (Wells 159). In essence, Henry felt the need to argue on behalf of the inclusion of a woman's scientific contributions in the context of the conference. Foote’s paper was presented at a moment in history when the barriers blocking women’s participation in the sciences were virtually ironclad. As Sarah Richardson observes in 2020, “In the entire 19th century, American women published only 16 physics papers, and only two of those appeared before 1889. Foote wrote both” (25).

The mere fact of Eunice's involvement, even through a substitute reader, garnered national attention and caused a stir in public discourse almost immediately. In September 1856, an editorial appeared in Scientific American, bearing the tongue-in-cheek title “Scientific Ladies—Experiments with Condensed Gases.” It suggests that debate surrounding Eunice's presence in the conference had less to do with atmospheric dynamics as much as it did with women’s rightful ability to participate in public discourse, both scientific and civil. “The experiments of Mrs. Foot [sic] afford abundant evidence of the ability of woman to investigate any subject with originality and precision,” it says (5). Women’s separate cultural dispensation in American science was not the result of constitutional or cognitive deficiencies, but due to a lack of “the leisure or the opportunities to pursue science experimentally” (5). The few who were afforded such an opportunity “have shown as much power and ability to investigate and observe correctly as men” (5). Turning to the content of the presentation, the editorialist observes, “those who believe earth was once a fiery ball, attribute this ancient great atmospheric heat to the elevated temperature of the earth; but Mrs. Foot’s experiments attribute it to a more rational cause, and leave the Plutonists but a small foundation to stand for their theory” (5). An eyewitness review of the conference by one "Anthropos" appearing in the Unites States Magazine recalls that “a paper of considerable interest” was presented, penned by "Mrs. Eunice Foote" (363). Her participation leads Anthropos to complain, at length, “that so few of our countrywomen can be found who give any attention to science as amateurs (pardon the solecism!) or investigators—it is this fact that needs either explanation or apology” (363). Contrary to what might be expected, Eunice's paper was able to provoke a number of appeals on behalf of some broader measure of equity in the sciences.

First published in the November 1856 issue of The American Journal of Science and Arts, Eunice's paper was retitled as "Circumstances Affecting the Heat of the Sun's Rays," further distinguishing it from Elisha's work. Eunice describes her experimental process in this piece as beginning “with an air-pump and two cylindrical receivers of the same size” (382). She used the air pump to depressurize one of the cylinders, leaving the other at normal ground-level pressure, and then placed both cylinders in direct sunlight. In time, the temperature of the cylinder at regular pressure rose to 100 degrees Fahrenheit; the vacuumed cylinder at a lower pressure remained at 88 degrees. She reiterated the experiment, this time adding varying degrees of moisture to the two tubes. Observing the moisturized tube rise to a higher temperature, Foote defers to an everyday experience to support this result: “Who has not experienced the burning heat of the sun that precedes a summer shower?” (383). Even as pressure and moisture compounded the temperature rise of objects exposed to radiant sunlight, these variables paled in comparison to the effects of adding carbon gas to the tubes, in a third iteration of the experiment. “The highest effect of the sun’s rays I have found to be in carbonic acid gas,” she attests (383). This most-crucial procedural variation involved comparing the temperatures of a tube filled with unadulterated air versus one infused with carbon dioxide. The latter produced a heat spike of 30 degrees, between control and variable, in direct sunlight (383). The receivers infused with carbon dioxide had exponentially larger temperature increases, especially in relation to other naturally occurring atmospheric gases, like oxygen or hydrogen. She cautions—and it is hard not to read these words as a caution—“An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature; and if as some suppose, at one period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature from its own action as well as from increased weight must have necessarily resulted” (383). The importance of her finding here is difficult to overstate. As Jeff Hecht sums it up in March 2020, this “was the first time anyone had suggested changes in the atmosphere could change climate.”

Eunice Foote used pumps to conduct her experiments at a time when she happened to live in an epicenter of the American pumpmaking industry. In Seneca Falls, know-how regarding the dynamic interactions of heat, flow, pressure, and the elements could make or break fortunes. Such knowledge, for example, made Eunice’s neighbor, pumpmaker Henry Seymour, a very wealthy man. The same elemental forces could also quite literally mean life or death, as evident in the staggering, catastrophic fires that plagued the pumpmaking enterprises of Henry William Seymour. A string of explosions at the factory he opened likely hobbled him financially and contributed to his departure from the village in the 1860s. While local innovations in pump engineering in this period were being applied to mass produce garden sprinklers and fire engines, Eunice Foote put the same local knowledge to use in order to study the natural world and its history.

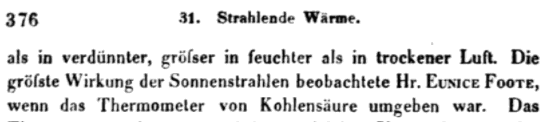

"Circumstances Affecting the Heat of the Sun's Rays" merited inclusion in international bibliographies during the 1850s. It is cited in publications by German scientific societies, in the Bibliotheca historico-naturalis physico-chemica (1856), Zeitschrift (1857), and Die Fortschr itte der Physik (1859). Failing to pick up on the name “Eunice” being traditionally female in English, Die Fortschritte credits the paper to “Hr. Eunice Foote,” as it provides a synopsis of her experiments in German (376).

itte der Physik (1859). Failing to pick up on the name “Eunice” being traditionally female in English, Die Fortschritte credits the paper to “Hr. Eunice Foote,” as it provides a synopsis of her experiments in German (376).

Prior to the recent rediscovery of "Circumstances Affecting the Heat of the Sun's Rays," Irish scientist John Tyndall had been credited with making the same finding regarding atmospheric carbon dioxide in 1859. Unaware of or indifferent to Foote's work, Tyndall used spectroscopy to understand the added impact that infrared light had on carbon dioxide's property of heat absorption. Foote had alternatively focused on the impacts of the visible spectrum of sunlight alone (Jackson). But don’t pity Tyndall for getting scooped by Eunice Foote. He is still recognized for his successful answer to what is, perhaps, the most common question about the natural world. He figured out why the sky is blue (Royal Institution).

In August 1857, Eunice participated in the twelfth AAAS conference, held at Montreal. This time around, the program lists a paper “By Mrs. Eunice Foote, of Seneca Falls, N.Y.” without identifying a proxy reader (123). This suggests not only that she was in attendance as the paper was read on August 13, but that she also might have been the individual reading it. Doing so would have represented a considerable violation of the still-extant taboo against women speaking aloud in public. Titled “On a New Source of Electrical Excitation,” this paper finds that “the compression or expansion of atmospheric air produces an electrical excitation” which has “an important bearing in the explanation of several atmospheric and electrical phenomena” (386). For this experiment, she again utilized an “ordinary air-pump of rather feeble power,” glass tubes, and an electrometer (386). Observing pressurized cylinders over the course of eight months, she observed how pressure variations in cooler, drier atmospheres creates an electrical charge. She concludes in the paper that “fluctuations of our atmosphere produce impressions and expansions sufficient to cause great electrical disturbances” to the effect that “the tidal movements of our atmosphere produce regular systematic compressions twice in twenty-four hours,” comparing this electrical excitation to the tidal forces of the sea (386, 387). Foote supports speculation on the physics of the upper atmosphere to this effect, already put forth by Becquerel, Gay Lussac, and Humboldt. “On a New Source of Electrical Excitation” was published in the journal of the AAAS in November 1857, the byline belonging to “Mrs. Elisha Foote.” It would be subsequently reprinted in its entirety in The London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science in 1858.

Foote’s efforts in the scientific community were still well-remembered by 1872. An issue of Popular Science recalls that, as one of the earliest female contributors to AAAS conferences, “Mrs. Elisha Foote prepared a paper, the result of her experimental investigations on heat, which was read at the meeting in Albany in 1856” (“Notes” 768). Illustration, 1860 Patent Application

Illustration, 1860 Patent Application

After the scientific endeavors of the 1850s, the Footes would move away from Seneca Falls for reasons that are not clear. They would settle in Saratoga Springs, 180 miles to the east, by 1860. I could not find the Footes in Saratoga County census records from this period. Saratoga Springs is, however, identified as the place of residence in two patent applications filed by Eunice during that decade. If the 1850s were a time of inquiry, the 1860s would be a time of invention.

Filed on May 15, 1860, Eunice’s first stand-alone patent application is intended as a type of filling for footwear, designed to “prevent the squeaking of boots and shoes.” It incorporates strips of leather and india rubber into an insert that would be fastened to the shoe's inner sole by pegs. These insoles could be trimmed to match shoe size before being added to the shoe. Daughter Mary Foote serves as one of the two required witnesses in the document.

Eunice filed a second patent application on November 22, 1864, in which she is identified as a resident of Saratoga Springs. This application was for a paper-making machine designed to produce stronger fiber paper. This would be effected by randomly reorienting the direction of the paper’s pulp before it was pressed. Paper made with pulp strands that all ran parallel, according to the application, yielded paper that was spongy and weak. By manipulating the direction of the pulp fibers into a crosshatch, the paper could be rendered tougher, smoother, and less spongy. “I have remedied this defect,” Eunice writes, “by causing the fluid pulp when it approaches the cylinder to acquire its motion and move along with it, so that as between the two there is no movement, and the pulp is deposited upon the cylinder the same as upon the sieve in handmade paper.” A group of slats attached to the cylinder and pulled by rubber belts could distribute the pulp so that it would set more multi-directionally. An “A. Newton” is one of the application’s witnesses; Eunice had two living sisters at that time, Amanda and Adeline, who might have performed this function. Holding patents 45,148 and 45,149, respectively, Elisha and Eunice are listed together in the U.S. Patent Office’s report on applications filed in 1864 (922). Elisha's invention for  Illustration, 1864 Patent Applicationimproving the runners of skates is followed immediately by Eunice's paper-making device.

Illustration, 1864 Patent Applicationimproving the runners of skates is followed immediately by Eunice's paper-making device.

This second invention of Eunice's subsequently received accolades in paper-making circles. A blurb in the American Artisan, reprinted from The Boston Sunday Times, praises “the invention of Mrs. Eunice N. Foote” (298). It represented a considerably less expensive alternative to the Fourdrinier papermaker, while rendering output of equal quality. “We do not doubt,” it adds, “that paper thus made will be the favorite in the market” (298). John L. Ringwalt’s 1871 American Encyclopaedia of Printing contains an entry for the invention as well, listing “Eunice N. Foote, Saratoga Springs, N.Y.” as its creator (233).

Eunice and Elisha’s preoccupation with new inventions would bring about a career move on his part in the 1860s. In 1864, Elisha received an appointment to the federal Patent Commission's Board of Appeals (Cyclopaedia 488). Later, in July 1868, The Yates County Chronicle announces that Elisha, here “of Geneva,” has been appointed U.S. Commissioner of Patents. In a column directly across from this news of Isaac's promotion, a brief two-line report discloses that two fires had occurred in Seneca Falls the previous week (“Jottings"). This new position required Elisha to reside in Washington, D.C. The 1868 and 1870 editions of Boyd’s Directory for the Washington area list him boarding at the National Hotel, located at Pennsylvania Avenue and 6th Street (146, 242).

Eunice, it seems, did not accompany her spouse to the nation’s capital. I was unable to find any record of her whereabouts at any point in the 1870s. She resurfaces briefly in the 1880 census for St. Louis, Missouri. Elisha and Eunice, now 71 and 61, both "at home," reside with daughter Mary Foote Henderson and her spouse, John Henderson, a former U.S. senator. An 1880 city directory for St. Louis gives the Hendersons’ residence as 3010 Pine Street (Gould 478).

After this, Eunice becomes even more itinerant and difficult to trace. Elisha would pass away in St. Louis on October 24, 1883. He is buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York (“Elisha Foote”). His probate letter lists Eunice's place of residence as New York City.

In May 1888, the last year of her life, Eunice, named as “administratrix” of her husband's estate, sued Edward A. Stone and Louis Stein in New York Circuit Court. Her suit argued that Stone and Stein had infringed upon a patent held by Elisha, which had involved some improvement for bag ties (Federal Reporter 205). A judge, however, rejected Eunice’s filing.

Eunice Newton Foote passed away on September 30, 1888, at age 69, in Lenox, Massachusetts. She is interred in the family mausoleum in Brooklyn, and her will was executed in New York City (“Eunice Foote”). Now remembered as the “Mother of Climate Change,” Eunice received a brief, unceremonious obituary in The New York Tribune on October 3 (Brazil). It was the only remembrance of her life at the time of her death that I was able to locate (“Died”).

"Foote- September 30 at Lenox, Mass. Eunice N. Foote, wife of late Elisha Foote, in the 70th year of her age. Funeral private. Internment at Greenwood."

Eunice Newton Foote's "Circumstances Affecting the Heat of the Sun's Rays" gestured to a new area of scientific inquiry in regard to human-made changes to global climate. The climatic processes she discovered will undoubtedly have an impact on civilization and the environment in the 21st century. At the time of its publication, the essay's insistence upon the inclusion of women in the sciences also constituted its own radical, progressive political statement.

Works Cited

American Art-Union. Transactions of the American Art-Union, for the Year 1847. American Art Union, 1848.

American Association for the Advancement of Science. Tenth Meeting of the Association: Commencing Wednesday Aug. 20,1856 at 10 O’clock A.m. at Capitol in the City of Albany, Etc. Van Benthuysen, 1856.

---. Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Eleventh Meeting, Held at Montreal. Lovering, 1858.

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Patents for 1864. Government Printing Office, 1866.

Bibliotheca historico-naturalis physico-chemica et mathematica. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1857.

Boyd, William. Boyd’s Directory of Washington and Georgetown. 1868.

Boyd, William. Boyd’s Directory of Washington and Georgetown. 1870.

Brazil, Rachel. “Eunice Foote: The Mother of Climate Change.” Chemistry World, 20 Apr. 2020, https://www.chemistryworld.com/culture/eunice-foote-the-mother-of-climate-change/4011315.article. Accessed 27 Jun 2020.

Brigham, DeLancey. Brigham’s Geneva, Seneca Falls, and Waterloo Directory and Business Advertiser, For 1862 and 1863. 1862.

Coakley, Katie. “Eunice Foote: Scientist and *Gasp* a Woman.” Emma Willard School, 23 Apr. 2018, https://www.emmawillard.org/news-detail?pk=1004269. Accessed 27 Jun 2020.

Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft. Fortschritte der Physik. Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft, 1859

“Died.” New York Tribune, 3 Oct. 1888, p. 7.

“Elisha Foote Family.” Federal Census, 1850. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Jun. 2020.

“Elisha Foote.” Findagrave.com, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/90957196/elisha-foote. Accessed 29 June 2020.

“Elisha Foote Probate Letter.” St. Louis, Missouri, Probate Court. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Jun. 2020.

“Eunice Newton Foote.” U.S. Passport Applications, Saratoga Springs, New York, 1862. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Jun. 2020.

“Eunice Foote.” Massachusetts Death Index, 1888. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Jun. 2020.

“Eunice Foote.” Findagrave.com, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/102362994/eunice-foote. Accessed 29 June 2020.

“Eunice Foote Probate Letter.” New York City, Probate Court. Ancestry.com, Accessed 27 Jun. 2020.

The Federal Reporter. West Publishing Company, 1888.

“Foote House Site.” Women’s History, New York State. https://web.archive.org/web/20170327154541/http://nywomenshistory.com/trailsite.php?tid=277. Accessed 30 June 2020.

Foote, Elisha. “On the Heat in the Sun’s Rays.” The American Journal of Science and Arts, vol. 22, no. 66, 1856, pp. 377–381.

Foote, Eunice. "Circumstances Affecting the Heat of the Sun's Rays." The American Journal of Science and Arts, vol. 22, no. 66, 1856, pp. 382–3.

---. “On a New Source of Electrical Excitation. The American Journal of Science and Arts, vol. 25, no. 70, 1857, pp. 386-7.

---. “On a New Source of Electrical Excitation.” The London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, vol, 15, no. 99, 1858 pp. 239-240.

---. “Patent Application: Filling for the Soles of Boots and Shoes”. US28265A, 15 May 1860. https://patents.google.com/patent/US28265A/en.

---. “Patent Application: Improvement in Paper-Making Machines.” US45149A, 22 Nov. 1864. https://patents.google.com/patent/US45149/en?oq=US45149.

“Foote’s Improved Paper-Making Machine.” American Artisan, 13 Nov. 1867, p. 268.

Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin. Zeitschrift. D. Reimer, 1857.

Gould, David B. Gould’s St. Louis Directory, for 1880. David B. Gould, 1880.

Hecht, Jeff. “Something’s a-Foote with Climate Science History: John Tyndall, Eunice Foote, and the Greenhouse Effect.” SPIE, 20 Mar. 2020, https://spie.org/news/photonics-focus/marapr-2020/tyndall-foote-and-the-greenhouse-effect?SSO=1. Accessed 27 Jun. 2020.

Huddleston, Amara. “Happy 200th Birthday to Eunice Foote, Hidden Climate Science Pioneer.” 17 July 2019. Climate.gov, Accessed 27 Jun. 2020.

Jackson, Roland. “Eunice Foote, John Tyndall and a Question of Priority.” The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science, 13 Feb. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsnr.2018.0066 . Accessed Jun 29 2020.

“John Henderson Family.” Federal Census, 1880. St. Louis, Missouri. Ancestry.com. Accessed 27 Jun. 2020.

“Jottings.” Yates County Chronicle, 23 July 1868, p. 5.

Leonard, Ermina Newton. Newton Genealogy, Genealogical, Biographical, Historical: Being a Record of the Descendants of Richard Newton of Sudbury and Marlborough, Massachusetts 1638. Higginson Book Company, 1915.

Marquis, Albert and John Leonard. Who’s Who in America, 1903-1905. Marquis, 1906.

McNeill, Leila. “This Lady Scientist Defined the Greenhouse Effect But Didn’t Get the Credit, Because Sexism.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/lady-scientist-helped-revolutionize-climate-science-didnt-get-credit-180961291/. Accessed 29 June 2020.

The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. J. T. White Company, 1897.

“Notes.” The Popular Science Monthly, October 1872, pp. 767-8.

Reed, Elizabeth Wagner. American Women in Science Before the Civil War. U of Minnesota, 1992.

Report of the Women's Right Convention. Rochester: John Dick, 1848.

Richardson, Sarah. “Suffragist Scientist.” American History, vol. 54, no. 6, 2020, pp. 24-5.

Ringwalt, John Luther. American Encyclopaedia of Printing. Menamin & Ringwalt, 1871.

The Royal Institution. “John Tyndall’s Blue Sky Apparatus.” https://www.rigb.org/our-history/iconic-objects/iconic-objects-list/tyndall-blue-sky. Accessed 30 June 2020.

“Science and Savans in America.” United States Magazine, vol. 3, no. 4, 1856, pp. 361-367.

“Seneca Falls Village in 1852.” Maps of Seneca County & Various Towns. https://www.co.seneca.ny.us/maps-of-seneca-county-various-town/. Accessed 9 June 2020.

Schwartz, John. “Overlooked No More: Eunice Foote, Climate Scientist Lost to History.” The New York Times, 27 Apr. 2020, https://nyti.ms/34SIWD8.

“Scientific Ladies—Experiments with Condensed Gases.” Scientific American, vol. 12, no. 1, 1856, p. 5.

“Seneca Falls in 1850.” Maps of Seneca County & Various Town – Seneca County, New York. https://www.co.seneca.ny.us/maps-of-seneca-county-various-town/. Accessed 9 June 2020.

“Seneca Falls Village in 1852.” Maps of Seneca County & Various Town – Seneca County, New York. https://www.co.seneca.ny.us/maps-of-seneca-county-various-town/. Accessed 9 June 2020.

Sorenson, Ray. “Eunice Foote's Pioneering Research On CO2 And Climate Warming.” Search and Discovery, 31 Jan. 2011 http://www.searchanddiscovery.com/documents/2011/70092sorenson/ndx_sorenson.pdf. Accessed 29 Jun. 2020.

Sotheby’s. “Auction of ‘Circumstances Affecting the Heat of the Sun’s Rays.’” Sotheby’s, https://www.sothebys.com/buy/5c983999-f7a4-400b-a60d-08679a3ca25d/lots/1b56949a-d11c-4977-bffc-1cf024c10aa1. Accessed 29 June 2020.

United States Patent Office. Annual Report of the Commissioner of Patents. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1866.

Wells, David. Annual of Scientific Discovery; Or, Year-Book of Facts in Science and Art, for 1857. Gould and Lincoln, 1857.

Wilkinson, Katharine. “The Woman Who Discovered the Cause of Global Warming Was Long Overlooked. Her Story Is a Reminder to Champion All Women Leading on Climate.” Time, 17 July 2020, https://time.com/5626806/eunice-foote-women-climate-science. Accessed 29 Jun. 2020.

Yocum, Barbara A. The Stanton House: Women’s Rights National Historic Park, Seneca Falls, New York. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1998.