Signer #76, David Spalding: "One More Mystery..."

Signer #76, David Spalding

Born: November 20, 1792, Columbia County, New York

Died: May 12, 1867, Vineland, New Jersey, Age 74

Occupation: Farmer

Local Residence: Eibert Road, Spafford, Onondaga County

The life of Signer #76, David Spalding (often given interchangeably as “Spaulding”), ended under unusual circumstances. At the time of his passing, David and his spouse, Lucy or Lucelia (Signer #57), had been married for 52 years. They had spent the better part of their married lives running a farm in Spafford, Onondaga County. Both individuals died, however, over 285 miles away from their home, in Vineland, New Jersey. Stranger still, David and Lucy died within three days of one another: he shuffled off this mortal coil on Sunday, May 12, 1867, and she died the following Wednesday. I was able to generate a plausible explanation as to why the Spaldings had journeyed so far from Spafford. What exactly befell them in New Jersey, on the other hand, must remain an enigma.

My research into David Spalding’s life was greatly aided by family trees constructed by subscribers on Ancestry.com. I also received crucial leads from The Spalding Memorial, an intergenerational genealogy, published by Samuel Jones Spalding in 1872 and again by Charles Warren Spalding in 1896.

Signer #76 was born on November 20, 1792, and spent his early life in Schaghticoke, now in the northwestern corner of Rensselaer County (although in the 1865 census, he situates his birthplace in neighboring Columbia County). David was one of Jeremiah and Elizabeth/Betsey Day Spalding’s fourteen children (S. Spalding 72, 136). From these parts, he eventually migrated “to Lake Pleasant, Hamilton Co., N.Y.; thence, in 1829, to Otisco, N.Y., thence, in 1840, to Spafford, N.Y.” (S. Spalding 252). The Spalding Memorial specifies that Spafford was, in fact, David’s “residence at the time of his death,” even though it was not the location where he died—a point I examine below (252).

David married Lucelia Carey on March 26, 1815 (S. Spalding 252). They would have seven children: Perlina, Frances-Clark, Isaac, Elizabeth, Eunice, David-Leland, and Lewis. Of these, all were born “in Northampton, N.Y., except Lewis, who b. in Otisco, N.Y.,” indicating that the couple transitioned to the Finger Lakes Region from eastern New York after marrying and having six of their seven children (C. Spalding 375).

David and Lucy established a farm in Spafford by 1840. Judith Wellman and colleagues have located the Spalding home, which still stands, on Eibert Road, a thruway connecting the southeastern shoreline of Skaneateles Lake to Otisco Lake (152). David Spalding appears as a head of household in the 1840 census for Spafford. Residing with him are a female in her forties, presumably Lucy; one male, other than David, in his fifties; a male child; a male teenager, and two teenage females—the younger individuals corresponding to David and Lucy’s children Eunice, Elizabeth, David-Leland, and Lewis.

Lucy and David were both in their fifties by the time of the Seneca Falls Convention. John Dick’s 1848 reproduction of the Declaration of Sentiments renders his name erroneously as “David Salding,” an obvious typo. “Lucy Spalding” is given correctly in the same document (11). Their home on Eibert Road sits just over 29 miles, by land, away from the Wesleyan Chapel. This would have been no small distance to cover for the Spaldings in 1848, without the benefit of modern transportation. The American Practical Mechanic Pocket Book and Almanac (1850) states that a horse carrying a “soldier and his equipments,” the equivalent of about 250 pounds, could safely travel no more than 25 miles in an eight-hour day (31). The Penny Mechanic, an 1837 almanac, puts the progress of a horse with a cart at only 20 miles in a day (18). Going any farther than this could seriously endanger the health of the animal. If the Spaldings traveled by horse, they undertook a multi-day trip to reach Seneca Falls. This represents a considerable investment of time and resources on their part, especially given the inconvenient, seven-days advance notice put out by convention organizers.

The commitment and mobility evidenced by the ground the Spaldings must have covered suggest that they were fully enmeshed in the regional network of non-local activists drawn to the Convention. This intimation rings true in a North Star article penned by Frederick Douglass and uncovered on The Syracuse and Onondaga Freedom Trail website. Douglass, writing as “F.D.,” updates readers on his “Meetings thus far” in that calendar year. The first of these “was held at Seneca Falls, in the Wesleyan Chapel,” which I understand as a reference not to the 1848 Convention, but rather as a subsequent speaking engagement held there that spring. Following this, Douglass “went to Auburn. Through the kind agency of my friend, E. Capron, a meeting had been appointed for me, in the old Universalist church.” Here Douglass acknowledges Eliab Wilkinson Capron, Signer #96, who had become, by then, the de facto agent and publicist for the Fox Sisters and their brand of seance-based spiritualism. This meeting with Douglass occurred shortly before Capron relocated to Rhode Island by the time of the 1850 census.

Douglass continued on to Onondaga where he “was met at Skaneateles by David Spalding, from Borodino, who kindly came to convey me from the former to the latter of my appointments, and after meeting, he took me in his wagon, and brought me to his house, eight miles toward Barodino [sic]. The meeting was held in the Methodist church, and was well attended.” Douglass' mention of Borodino here designates a hamlet within the town of Spafford. Douglass continues lavishing praise upon his hosts: “My visit to Borodino was a very pleasant one. Mr. Spalding and family know well how to make the weary stranger at home, and I left feeling grateful for their kind attentions, and the aid they mutually rendered me. The anti-slavery lecturer need never fear to go to the home of David Spalding ; for though unpretending, and in humble circumstances, he takes sincere pleasure in lending a helping hand to all devoted laborers in this cause.” Clearly, David Spalding had gone great lengths to support Douglass’ itinerant activism and fundraising on behalf of the cause of Abolition. The town of Skaneateles is, in fact, between 7.7 and 8.3 miles from Eibert Road. This would have been a sizeable roundtrip of at least 15.4 miles for Spalding and could conceivably have taken the better part of a day.

A "David Spalding" subsequently appears on a subscribers list published in The North Star during January 1850, which otherwise includes Henry Stanton (“Receipts”).

Their signatures only three spaces removed in the Declaration, the ordinal proximity of Signer #73 and #76 translated into an ongoing social bond after the Convention. Douglass and Spalding are separated only by Henry W. Seymour (#74) and Henry Seymour (#75), two namesakes with their own exceptional, potentially fraught relationship.

In the 1850 Spafford census, David and Lucy, 56 and 54, are recorded cohabitating with Eunice, 26; David-Leland, 24; Lewis, 15; and an 80-year-old named Elizabeth Fowler, who is possibly David's remarried mother. Their wealth is assessed at $4,000.

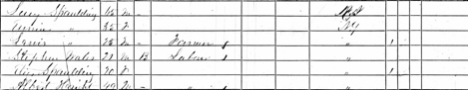

By the 1860 census, David, 67, and Lucy, 65, live with Eunice, 35, and Lewis, 25. Also living in the home are are Eli Spalding, a likely relative, as well as two laborers—including one Stephen Wales, a 21-year-old African-American.

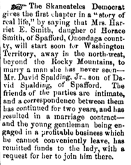

Son David-Leland Spalding is absent from the 1860 census because he had moved to the West Coast. And the extraordinary terms of his long-distance relationship and marriage to Harriet Smith, also from Spafford, would grab the attention of the national media (C. Spalding 646). After settling in the Oregon Territory, David-Leland and Harriet were i ntroduced by a mutual acquaintance and began corresponding by mail. Based on their being pen pals, they agreed to wed one another, having never met in person. In January 1860, newspapers announce that Harriet was planning to travel to Washington State “beyond the Rocky Mountains, to marry a man whom she had never seen” (“Skaneateles Democrat”). News of the romance, sight unseen between David and Harriet, was reprinted by newspaper outlets in Boston; Cincinnati; Camden, New Jersey; New York City; Indiana; Kansas; Connecticut; Michigan; and elsewhere. David eventually became a reverend, and he and Harriet would reside in in Yam Hill, Oregon, and Endicott, Washington (C. Spalding 646).

ntroduced by a mutual acquaintance and began corresponding by mail. Based on their being pen pals, they agreed to wed one another, having never met in person. In January 1860, newspapers announce that Harriet was planning to travel to Washington State “beyond the Rocky Mountains, to marry a man whom she had never seen” (“Skaneateles Democrat”). News of the romance, sight unseen between David and Harriet, was reprinted by newspaper outlets in Boston; Cincinnati; Camden, New Jersey; New York City; Indiana; Kansas; Connecticut; Michigan; and elsewhere. David eventually became a reverend, and he and Harriet would reside in in Yam Hill, Oregon, and Endicott, Washington (C. Spalding 646).

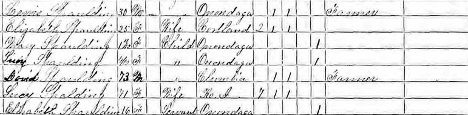

In the 1865 state census, David and Lucy, 73 and 71, live with Lewis and his wife, Elizabeth. Lewis is designated as head of household in this census, suggesting that he might have taken the lead in the operation of the family farm. Lewis and Elizabeth have two toddlers, Mary and Lucy. A teenage “servant” and possible relative named Elizabeth Spaulding lives under the same roof.

Shortly after this, David and Lucy’s lives together came to an abrupt and mysterious conclusion in the spring of 1867. The 1916 Vineland Historical Magazine marks their deaths as occurring in Vineland, New Jersey, on May 12 and May 15, respectively (Andrews 55). By this time, they had farmed and raised children in Spafford for at least 27 years. Just what had compelled them to venture so far from home?

The likely answer to the Spaldings’ presence in Vineland involves the intentional community that had recently been established there. Charles K. Landis founded Vineland in 1864 as an aspiring utopia and agrarian haven for spiritualists, suffragists, and other progressives. Welch’s Grape Juice, most famously, came into being as the Vineland Grape Juice Company. Dr. Thomas Welch created the brand there in an attempt to market a grape juice that did not ferment into wine—an attractive feature for Vineland's temperance-minded local citizenry (DiUlio).

According to Margery Post Abbott, a number of the members of the Waterloo/Junius Meeting of the Friends of Human Progress had also been drawn to the Vineland experiment as some of the community's pilot stakeholders (357). This group, the Friends of Progress broke away from the Hicksite Quakers in 1850s, based on its members’ more-radical positions on slavery, women’s rights, and pacifism. A number of Declaration signers, including Margaret Schooley (#7), held leadership roles in the meeting's embryonic Waterloo enclave.

Like the Spaldings, Margaret and George Pryor, Signers #3 and #93, also hailed from the Skaneateles area and moved to Vineland during their golden years. Active in the Friends of Progress, the Pryors celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary at Vineland, and George would be elected a community trustee in 1864 (Vineland Magazine 38-9, 59).

During its existence, Vineland would welcome pro-suffrage activists like Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton (#4), and Lucy Stone, among others. With the examples of the Spaldings and the Pryors in mind, it might be considered that Vineland was serving as a kind of utopian retirement community for affiliates of the Friends of Progress and former signers of the Declaration.

This context does much to explain the reasons why the Spaldings were on a sojourn in Vineland, from which they did not return. David and Lucy were no spring chickens by this point. David was 74 and Lucy was 72 at the time of their passing (Andrews 55). Yet, their respective deaths occurred only three days apart, and, despite their advanced ages, it still remains a curiosity. What ended their lives so closely to one another? Were they strickened suddenly by the same disease? Did some traffic accident mortally injure them, with David succumbing first, only to have Lucy hold on a few days longer? Did Lucy die of grief in the aftermath of her husband's loss, having spent more than half a century married?

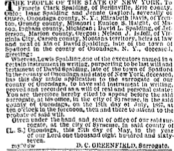

A notice of trustee appeared in The Albany Evening Journal the following July, with Lewis acting as an executor of David's will. It notifies next of kin, primarily the Spaldings' living children, who now reside in Oregon, Missouri, Michigan, and Montana ("People"). This was the only item, by way of obituary, that I could locate for David.

I could not find any records pertaining to the location of the couple's gravesites, but Vineland is the most likely candidate and merits a future research trip. For the time being, the curious nature of David and Lucy's deaths remains unknown.

Many of the lifelines of the Declaration’s signers are doomed to remain clouded, undocumented, and indeterminate. For now, the end of David and Lucy Spalding’s lives will persist as just one more mystery.

Works Cited

Abbott, Margery Post, et al. Historical Dictionary of the Friends (Quakers). Scarecrow Press, 2012.

American Practical Mechanic. American Practical Mechanic’s Pocket Book and Almanac. Kingsley & Langbottom, 1850.

Andrews, Frank DeWette. The Vineland Historical Magazine. Vineland Historical and Antiquarian Society, 1916.

Collins, George K. Spafford, Onondaga County, New York. Pipe Creek Pub., 1902.

“David and Lucelia Spaulding Home.” The Freedom Trail in Syracuse and Onondaga County, NY. http://pacny.net/freedom_trail/. Accessed 17 Oct. 2020.

“David Spalding Household.” Federal Census, 1840. Spafford, New York. Ancestry.com.

Accessed 20 Oct. 2020.

“David Spalding Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Spafford, New York. Ancestry.com.

Accessed 20 Oct. 2020.

“David Spalding Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Spafford, New York. Ancestry.com.

Accessed 20 Oct. 2020.

DiUlio, Nick. “150 Years Ago, Vineland Was a Budding Utopia in South Jersey.” www.NJmonthly.Com. https://njmonthly.com/articles/jersey-living/visionary-vineland/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

Douglass, Frederick. “Editorial Correspondence.” The North Star, 13 Apr. 1849, p. 4.

“Lewis Spalding Household.” Federal Census, 1865. Spafford, New York. Ancestry.com.

Accessed 20 Oct. 2020.

“Marrying by Correspondence.” Penny Press (Cincinnati, Ohio), 9 Jan. 1860, p. 2.

The Penny Mechanic: A Magazine of the Arts and Sciences. Doudney, 1837.

"The People of the State of New York." Albany Evening Journal (New York), 3 Jul. 1867, p. 4.

Report of the Women's Right Convention. Rochester: John Dick, 1848.

“Receipts.” The North Star, 1 Jan. 1850.

“Romance in Real Life.” Alexandria Gazette (Virginia), 2 Jan. 1860, p. 2.

“Romance in Real Life.” Emporia News (Emporia, Kansas), 28 Jan. 1860, p. 3.

Spalding, Charles Warren. The Spalding Memorial: A Genealogical History of Edward Spalding of Virginia and Massachusetts Bay and His Descendants. Spalding Documentation Services, 1896.

Spalding, Samuel Jones. Spalding Memorial; a Genealogical History of Edward Spalding, of Massachusetts Bay, and His Descendants/ Samuel J. Spalding. Alfred Mudge & Sons, 1872.

“Skaneateles Democrat.” Yates County Chronicle (Penn Yan, New York), 5 Jan. 1860. P. 1.

“The Skaneateles Democrat.” Cass County Republican (Michigan). 26 Jan. 1860, p. 4.

“The Skaneateles Democrat.” Boston Traveler. 3 Jan. 1860, p. 4.

“The Skaneateles Democrat.” Columbian Register (New Haven, Connecticut), 14 Jan. 1860, p. 4.

“The Skaneateles Democrat.” New Albany Daily Ledger (New Albany, Indiana), 22 Dec. 1859, p. 3.

“The Skaneateles Democrat.” Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper (New York, New York), 14 Jan. 1860, p. 5.

“A Story of Real Life.” Camden Democrat (New Jersey), 21 Jan. 1860, p. 3.

Vineland Historical and Antiquarian Society. Vineland. Arcadia Publishing, 2011.

Vineland Historical and Antiquarian Society. The Vineland Historical Magazine. 1918.

Wellman, Judith, et al. Women’s Suffrage in Central New York. Historical New York Research Associates, 2019.