Signer #84: Jacob Mathews, "The Liquor Dealer"

Best Candidate, Signer #84: Jacob Mathews

Born: 1805, New Jersey

Died: February 2, 1874, Waterloo, Age 68-9

Occupation(s): “Mason,” “Liquor Dealer”

Local Residence: 319 Main Street, Waterloo

The first half of the 1840s was a high-water mark for anti-alcohol fervor in Seneca Falls. In 1842, a law was passed “prohibiting the sale of liquor” within village limits. According to Judith Wellman, no new liquor licenses were granted in Seneca Falls for the next two years, from 1842 to 1843 (83). A temperance-themed parade marked village celebrations of the July 4th holiday in 1842, with alcohol-free toasts of “‘clear cold water’” (85). And the alcohol content of communion wine factored into an internal dispute among the local Presbyterian congregation in 1843—a point of contention about which Signer #14, Delia Mathews, was called to testify.

Contemporaneous and cross-pollinating, the Suffrage Movement and the Temperance Movement would become intimately interconnected in the coming decades. Because of alcohol’s associations with domestic violence and squandered income, the prospect of living without it would be construed as a right of survival for women. Both Suffrage and Temperance would reach parallel moments of fruition in the second decade of the 20th century: the failure of the 18th Amendment, ratified in 1919, has a very different legacy than that of the 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920.

Yet, the teetotaling ardor of 1842 was not destined to last forever—or, perhaps, it was not unanimous and absolute in Seneca Falls. I say this because a number of the signers profiled so far would, at one point or another in their lifetimes, take up livelihoods that depended upon the production and sale of alcohol. The livery owned by Signer #65, Experience Gibbs, and her spouse, Ansel, proudly advertised that whiskey and wine were sold on premises. The best candidate for Signer #71, Justin Williams, was an IRS gauger, responsible for monitoring the sale, distribution, and taxation of spirits. Signer #83, Robert Smalldridge, whose signature immediately precedes Jacob Mathews' ordinally, was a cooper, an occupation which typically involved the manufacture of barrels and kegs. The same aura of anti-temperance sentiment rings true for Jacob Mathews of Waterloo, the best candidate for Signer #84. Mathews was a stonemason at the time of the Convention but would later embark upon a career as a liquor retailer.

Having now created profiles for all three signers with the surname “Mathews,” I was surprised to find that they were not immediately related. Delia Matthews was from New York; the best candidate for Dorothy Mathews (#39) hailed from Connecticut; New Jersey is consistently listed as Jacob Mathews’ birthplace. In so many examples, family ties drove participation in the Convention. Yet, the reverse seems to be true in the case of Delia, Dorothy, Jacob, each unrelated.

Jacob Mathews is also the third male signer profiled (so far) whose wife did not sign the Declaration. In spite of her being alive, well, and in the area at the time of the Convention, the signature of Sarah Smalldridge, wife of Robert Smalldridge, is missing from the document. Susan Seymour, wife of Henry Seymour (#75), also did not sign. A cursory search has revealed the same is true for the signer immediately after Jacob Mathews, Charles Hoskins (#85). Hoskins' spouse, Mary, is absent from the Declaration, amounting to three consecutive signatories from the Men's Section whose spouses, curiously, failed to lend their names.

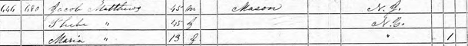

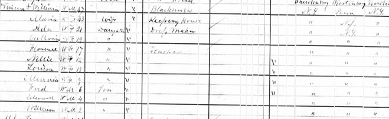

Searches for early traces of the life of Signer #84 revealed a “Jacob Mathews,” who appears in the censuses for Seneca Falls in 1830 and 1840:

In 1830, this individual cohabitates with an adult female in her 20s, and a female child under the age of 5.

In 1830, this individual cohabitates with an adult female in her 20s, and a female child under the age of 5.

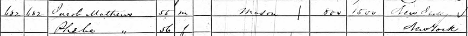

By the 1840 census, "Jacob Matthews" resides with 2 female children under the age of five, one female in her 50s, and one female in her 30s.

In an 1850 census record taken by Isaac Fuller, Jacob Mathews lives in Waterloo with the listed occupation of mason. He is 45 by 1850, and all subsequent censuses consistently date his birth year to 1805 and list his native state as New Jersey. Jacob lives with his spouse, Phebe, 45, who is a native of New York. Phebe and Jacob have a daughter Maria, age 13 in 1850 (so born around 1837).

In 1860, Jacob and Phebe appear briefly in nearby Geneva. He works as a mason and has an estimated worth of $2300:

On November 5, 1857, Maria married William L. Vincent of Waterloo (Jackson & Jackson 36). Their nuptials are also entered into local Presbyterian church records.

In DeLancey Brigham’s 1862 Seneca County directory, Jacob and Phebe have returned to Waterloo, keeping house on 319 Main Street (36). Jacob's name and address are listed directly before that of Jabez Mathews, the spouse of Delia Mathews.

Between 1862 and 1864, Jacob partnered with Abiram D. Babcock, a man more than 20 years his junior, to create Babcock and Mathews, liquor wholesalers. In the 1862 directory, A.D. Babcock is listed as a partner of one B. Stroyer, operating an establishment located at 1 Washington Street in Waterloo (18). The newly-created firm of Babcock and Mathews is, however, catalogued in both the 1864 and 1867 editions of The New York State Business Directory, found under “Wine and Liquor Dealers” (733, 830). In Hamilton Child’s 1867 Seneca County directory, Babcock and Mathews are “liquor dealers and saloon keepers,” plying their trade on Virginia Street and, conceivably, catering to traffic on the canal (173, 115).

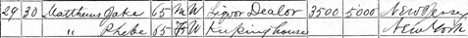

“Jake” and Phebe, now both 65, are counted in the 1870 Waterloo census. He is a “Liquor Dealor,” and she is responsible for “Keeping house.”

The Babcock and Mathews enterprise has evidently turned a profit—their assets are now valued at $8500 dollars.

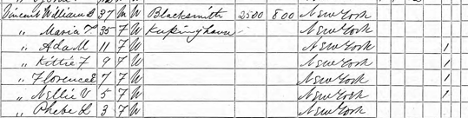

Also in Waterloo, daughter Maria and son-in-law William have started a family by the 1870 census. They have five daughters: Ada M., Kittie F., Florence E., Nellie V., and Phebe L.

Legal notices published during this period offer a glimpse into Jacob’s business dealings. A notification run repeatedly in The Daily Albany Argus during 1871 names Jacob as a defendant in a lawsuit filed by the Seneca Woolen Mills against its own stockholders. Other village notables from past installments of this blog—like Horace Bogue and Ansel Bascom—are also named as defendants. A pair of Declaration signers, Jacob P. Chamberlain (#88) and Charles L. Hoskins, are included in the suit. The notice claims that the dispute between the mill and its investors will be brought to trial before a referee in Seneca Falls on December 18, 1871 (“Supreme Court-Seneca”). I was unable to ascertain the exact nature of this legal matter, which will hopefully come to light in future research.

Elsewhere, a notice from April 13, 1871, placed in The Yates County Chronicle (and re-run thereafter), names Babcock and Mathews as complainants against the estate of one Daniel Lockwood, now administered by his widow. A parcel of land in Penn Yann, owned by the late Lockwood, is to be auctioned off in May, a move possibly designed to settle a debt that was owed to Babcock and Mathews (“Supreme Court-Yates”).

On January 6, 1873, Jacob’s business partner Abiram Babcock died at age 46 (Jackson & Jackson 101). The Yates County Chronicle reports that Babcock’s cause of death was consumption and that he left behind a widow and five children (“Died”).

Jacob Mathews died on Monday, February 2, 1874. The singular trace I could locate of his death was a brief probate letter filed on February 9, designating Phebe and another woman as co-administrators of his will. While Babcock’s passing was remarked upon repeatedly by local newspapers, I could find no similar mentions of Jacob’s death.

By 1880, Phebe, 77, and daughter Maria live in separate households on Elizabeth Street in Waterloo. William, Maria’s husband, works as a blacksmith and carriage mechanic. He and Maria, “Keeping House,” have nine children living with them: Ada, Catharine, Florence, Nellie, Louisa, Minnie, Fred, Edward, and William, who range in age from 2 to 21. The crowded house might explain why Phebe had moved near to her daughter while not moving in with her. After the 1880 census, Phebe Mathews disappears from record.

Maria and William would relocate to Rochester in subsequent censuses. In 1900, Florence, Louisa, Minnie, Fred, Edward, and William still reside with their parents:

Maria, now 78, and William, 82, appear in the 1915 state census for Rochester, with Florence, Minnie, and a son.

Maria, now 78, and William, 82, appear in the 1915 state census for Rochester, with Florence, Minnie, and a son.

Facta non verba or “Deeds not Words” would become an oft-repeated mantra within the Suffrage Movement. Many of the local signers’ livelihoods would come to rely on the liquor industry. It stands to reason, through deed, that the signers of the Declaration were not of one mind on the subject of temperance. No record exists of any hostility or contention between the dry and wet camps present at the Seneca Falls Convention. The question of alcohol must have been ancillary and only tangential in relation to the primary matter at hand.

Works Cited

Brigham, DeLancey. Brigham’s Geneva, Seneca Falls, and Waterloo Directory and Business Advertiser, For 1862 and 1863. 1862.

Child, Hamilton. Gazetteer and Business Directory for Seneca County for 1867-8. 1867.

“Died, of Consumption, at Waterloo.” Yates County Chronicle, 23 Jan. 1873, p. 3.

Jackson, Mary Smith, and Edward F. Jackson. Marriage and Death Notices from Seneca County, New York Newspapers, 1817-1885. Heritage Books, 1997.

“Jacob Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1830. Waterloo, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.

“Jacob Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1840. Waterloo, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.

“Jacob Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Waterloo, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.

“Jacob Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Geneva, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.

“Jacob Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Waterloo, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.

“Jacob Mathews Probate Letter.” Waterloo, New York, 1874. New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.

“Maria T. Mathews-William L. Vincent Wedding.” Presbyterian Church Records, Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.

“Phebe Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1880. Waterloo, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.

Report of the Women's Right Convention. Rochester: John Dick, 1848.

Sampson, Davenport & Co. The New York State Business Directory, Containing the Names, Business and Address of All Merchants, Manufacturers, and Professional Men throughout the State. 1864.

---. The New York State Business Directory, Containing the Names, Business and Address of All Merchants, Manufacturers, and Professional Men throughout the State. 1867.

“Supreme Court—County of Seneca.” Daily Albany Argus, 23 Nov. 1871, p. 3.

“Supreme Court—Yates County.” Yates County Chronicle, 13 Apr. 1871, p. 4.

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman’s Rights Convention. University of Illinois Press, 2010.

“William Vincent Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Waterloo, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.

“William Vincent Household.” Federal Census, 1880. Waterloo, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.

“William Vincent Household.” Federal Census, 1900. Rochester, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.

“William Vincent Household.” New York State Census, 1915. Rochester, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.