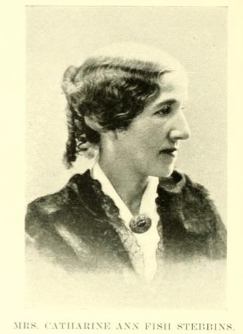

Signer #11: Catharine F. Stebbins, "The True Believer"

Signer #11: Catharine Ann Fish Stebbins

Born: August 17, 1823, Farmington, Ontario County, New York

Died: November 8, 1904, Rochester, New York, Age 81

Occupation(s): Activist, Educator, “Boarding”

Local Residence: West North Street, Rochester

Special thanks to the students of ENG 360 for the research assistance provided in the creation of this profile.

In contemporary sources, the Suffrage Movement is often caricatured as a redoubt of the leisure class. The thinking seems to have been that suffrage activism was a pursuit reserved only for otherwise-unoccupied women of means, with ample time and resources to champion the cause. Signer #11, Catharine Ann Fish Stebbins defies this generalization.

In her lifetime, she managed to become a fixture within the inner-circles of both the Anti-Slavery and Suffrage Movements. And, after participating in the Seneca Falls Convention, she would remain in the fight to win franchise for the rest of her natural life. She was deeply invested in prominent feminist organizations of the day—particularly the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the Association for the Advancement of Women (AAW). She kept these proverbial irons in the fire, even as she and her spouse never quite settled down into anything like a comfortable, middle-class existence. Instead, they lived as boarders, occupying rented backrooms, for the better part of four decades.

Moreover, Catharine Stebbins resided in the Midwest on a semi-permanent basis, beginning in the 1850s. She still regularly returned east for conferences and protests, to far-flung venues like Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. These excursions must have entailed back-breaking amounts of interstate travel. A seemingly relentless sense of commitment also impelled her to contribute to the controversial, then-heretical Woman’s Bible in the 1890s. In sickness and health, for richer and poorer, whether blasphemous or sanctified, Signer #11 persisted.

A version of Catharine’s life story is preserved in Frances Willard’s and Mary Livermore’s A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-Seventy Biographical Sketches (1893). Much of the same prose is subsequently repurposed in Ralph and Robert Greenlee’s Stebbins Genealogy (1904). In spite of its plagiarism, The Stebbins Genealogy is still a welcome rarity, for the simple fact that it records and even celebrates the career of a suffragist-in-the-family.

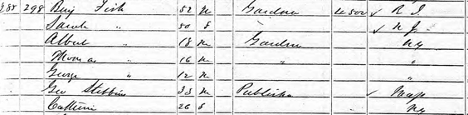

Catharine (on occasion, "Catherine") was born on August 17, 1823, in Farmington, Ontario County, the daughter of Benjamin Fish and Sarah David Bills. Benjamin and Sarah were Hicksite Quakers who had migrated to New York from Rhode Island and New Jersey, respectively. According to Ambrose Shotwell’s Annals of Our Colonial Ancestors and Their Descendants (1895), Sarah was a direct descendant of the sister of John Winthrop, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Benjamin was a distant cousin of both Lucretia Mott (Signer #1) and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Catharine was the eldest of six siblings: Mary; two Alberts, one born 1829, the second born in 1831; Thomas; and George (Shotwell 220). Catharine’s parents were themselves deeply committed to a raft of progressive causes, and their various pursuits held clear implications for Catharine's future as a reformer.

The Fish family moved north to Rochester some time around the year 1828. Willard and Livermore state that, from early adolescence, Catharine was dedicated to abolition. “Her first reform work was done between her twelfth and fifteenth years, and consisted of gathering names to anti-slavery petitions.” She also supported temperance and even kept “an anti-tobacco pledge," in an attempt to solicit the signatures of young men promising to swear off smoking (681). Catharine spent six months in a Quaker boarding school after turning 15. Thereafter, she began working as an educator, instructing her younger siblings as well as neighborhood children. Her success as an instructor was such that “she was requested to go before the board of examiners, that the people of the neighborhood might draw the school monies. She then took charge of the first public school in the ninth ward” of Rochester (681).

Benjamin supported the family as a gardener and through plant husbandry, which is, the cultivation of various varieties of produces. He is recorded at an 1851 New York agricultural exhibition showcasing six kinds of peaches and five kinds of plums (114, 115). Benjamin’s profession was evidently lucrative enough to allow him to serve as benefactor for promising activists. In The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, the author (#73) identifies Benjamin among the “true men of Rochester” who supported his earliest Anti-Slavery work in the city (234). Benjamin was also a subscriber to The North Star. In an 1851 letter to Douglass, Benjamin enclosed the $2 annual subscription fee for the newspaper, allowing that "I see many things in it with which I disagree," but still, "I believe it to be doing good anti-slavery work" (Letters 509).

Benjamin would also become a key stakeholder in the upstart intentional community at Sodus Bay. Established in 1844, the project was theoretically modeled after the phalanx system set down in the work of philosopher Charles Fourier. Disenchanted with the Hicksite Quakers by this time, Benjamin acted as Sodus Bay's first president and rented a room in the commune's main building (Kesten 65, 323). The enterprise attracted 300 individuals at its apex, but internal dissent over religious difference, disease, and debt forced it into a swift decline (Noyes 286-94). The Fish family resided at Sodus Bay from 1844 to 1847, right up to the time of its dissolution (Shotwell 220).

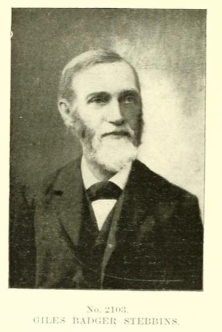

In spite of Sodus Bay's dwindling fortunes, Catharine was married there on August 17, 1846, her 23rd birthday, to Giles Badger Stebbins. Giles was born on June 24, 1817, in Springfield, Massachusetts. He had initially set out in life with the aim of attending Harvard Divinity School and becoming a Unitarian minister. Around age 25, however, he was wooed away from these pursuits, drawn instead to the avocation of an itinerant Anti-Slavery lecturer.

Ignoring Charles Fourier's open disdain for monogamy and matrimonial bondage, Catharine is not the only signer of the Declaration of Sentiments to have been married at Sodus Bay. Signer #96, Eliab Wilkinson Capron also joined the phalanx and wed his spouse, Rebecca, at the site in 1844.

The Fish family returned to Rochester after Sodus Bay went bust. The 1847 Daily American Directory for Rochester locates their home at West North Street, “near City Line” (109).

The Fish family returned to Rochester after Sodus Bay went bust. The 1847 Daily American Directory for Rochester locates their home at West North Street, “near City Line” (109).

Catharine would have been living in Rochester by the time of the Seneca Falls Convention, and she is the first Rochesterian signer profiled in this blog (so far). It bears mentioning that the journey to Seneca Falls is a trip of at least 50 miles, one-way. Whatever mode of transportation the group from Rochester resorted to, it could only have been a time-consuming, expensive, and arduous journey.

Breaking the taboo against women's public speech, Catharine took an active role in debate at the Convention. The History of Woman Suffrage singles her out as one of the convention-goers involved in discussions surrounding resolutions to be adopted, amended, or tabled (1:71). A Woman of the Century attests, “she made a short speech and contributed to a resolution in honor of Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, which was passed the next week in Rochester” (681). At that time, Elizabeth Blackwell was still in the process of studying to be a doctor at Geneva College Medical School, just west of Seneca Falls. Catharine's signature appears on the Declaration immediately after that of fellow Rochesterian Amy Post (#10).

After Seneca Falls, a successive convention was held in Rochester on August 2, 1848, with a handful of familiar characters: Mott, Douglass, Post, Elizabeth Cady Stanton (#4), Sarah Hallowell (#21), and Mary Hallowell (#29). Catharine served as one of the officers at this meeting, appointed as a secretary (Parker 346). A historical marker now located at the site of the Rochester meeting identifies Catharine's mother, Sarah, as one of the gathering's notables. Sarah delivered an address in the afternoon session, violating custom to set "forth some of the causes of woman's degradation, and urging her earnestly to come forward to the work of elevation" (Report).

Catharine's activities at the 1848 summer conventions received international attention in print write-ups. These accounts unfortunately cast the recent events in a somewhat unflattering light. An article in The New Orleans Daily Crescent, bearing the exasperated title “Another Woman’s Rights’ Convention,” names Catharine as one of the officers at the Rochester convention. The gathering was “of a similar character” to the one that had transpired at Seneca Falls. Catharine's name appears elsewhere in the the Kingdom of Hawaii's Polynesian, headquartered in Honolulu, the following March:

The Polynesian complains, with some hand-wringing, “We may expect to hear, ere long, of those engaged in this convention forming military companies, in order to carry out more fully their idea of the ‘rights of women.’”

Amidst these initial stirrings, the Fish household was swept up in yet another social movement then gaining momentum, spiritualism. Benjamin and Sarah would be early adopters of the techniques of séance first devised in April 1848 by the Fox Sisters in nearby Hydesville. Giles Stebbins later remembered that his parents-in-law were among the “earliest investigators” of metaphysical communication via "spirit wrappings" (Steps 224). He reports that the Sarah and Benjamin participated in an 1848 seance lead by Leah Fox Fish, the eldest of the clairvoyant sisters. At this encounter, a traveler recently returned from India was able to make contact with deceased Indian acquaintances (101).

By September 1851, Sarah and Benjamin were hosting séances in their own home. One gathering took the form of a spirit session again lead Leah Fox Fish, which was conducted with a group comprised of Giles, Sarah, Benjamin, Catharine, her siblings, as well as Amy and Isaac Post. Participants sat in silence for two hours before Giles was able to make contact with a number of his dead relatives, who correctly answered questions posed at them through a series of taps (226-7). The experience was so profound for Giles that he would be converted into a lifelong public advocate for spiritualism.

Benjamin was equally convinced. Thomas Hazard’s 1873 Mediums and Mediumship contains anecdotes of Benjamin personally serving as the medium in a series of séances. In one session, it is claimed that Benjamin made physical and verbal contact with posthumous apparitions of his late wife and two of his sons, Albert and Thomas (39-40). All indications suggest that Catharine—along with her mother, father, and husband—was a part of the mounting obsession regarding communication with the spirit world.

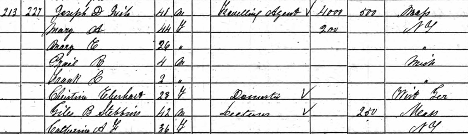

Even as revolutionary new ideas percolated in Rochester, Catharine and Giles would soon decamp from the city, for the first in a series of migrations west. From 1849 to 1850, the pair moved briefly to Milwaukee, most likely to support Giles' ambition of becoming a Unitarian minister. The demands of married life and westward migration in no way diminished Catharine's zeal for activism. A Woman of the Century remarks that Catharine began her career as a political writer shortly after reaching Wisconsin, publishing “her first letter in protest against the insubordinate position of women in the ‘Free Democrat,’” a local newspaper (562). The journey to the Midwest was ultimately short-lived. In the 1850 census, Catharine, 26, and Giles, 33 and a publisher, have moved back in with her parents in Rochester’s 3rd Ward. Also living in the home are brothers Albert, Thomas, and George Fish.

The first volume of The History of Woman Suffrage reports that Catharine was in attendance at national suffrage conventions held in Syracuse in 1852 and Albany in 1854. In Albany, she was appointed to the conference's Business Committee (1:519, 593). Back in Rochester in the 1850s, she had also become active in the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society.

The website Digital Commonwealth has preserved a number of letters penned by Catharine during this period. A handful are addressed to Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, living in Boston. In an April 1852 communique, she writes to Garrison about Frederick Douglass’ growing influence in Rochester. On a first-name basis referring to Signer #73, she writes, “as little sympathy as Frederick has in some quarters, he has friends and an influence yet.” She also reports to Garrison about Douglass' brooding reaction to an upcoming anti-slavery event, slated for the Independence Day holiday that year. Catharine writes of Douglass that initial planning for the festival program "called out a rain of bitter reflections from him, which yet carried many with him, as they did not see things in their true light.” Douglass’ remarks in this instance might be understood as an initial brainstorm of what would become “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” an oration delivered later at the festivities.

That Catharine is relaying intimate details to Garrison about Douglass’ mindset suggests that she could be counted among Anti-Slavery's vanguard at the time. She writes again to “My Dear Friend Garrison” in September 1854, imploring him to come to Rochester and speak before the Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society.

In December 1856, Catharine and Giles had their first child, a daughter named Mary Wendelline. In 1859, the small family completed a second migration west, settling this time in Ann Arbor, Michigan. This time, Giles worked to establish a Unitarian congregation among an “Independent Society,” a group of unaffiliated church-goers residing there (Greenlee & Greenlee 561).

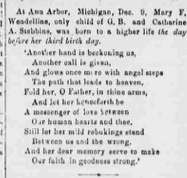

Mary Wendelline passed away in Ann Arbor in 1859, one day shy of her third birthday. In a record first uncovered by a user on Findagrave.com, The Anti-Slavery Bugle carried an obituary for the little girl, which includes the poem "Gone" by John Greenleaf Whittier.

In 1860, Catharine again wrote to Garrison, asking him to venture out to Ann Arbor. Ideally, he would lecture before an undisclosed group at the University of Michigan, referred to circumscriptively as the “’Student’s Association.’” The faculty and student body there, she reassures him, were entirely sympathetic to the cause of Abolition. In the 1860 census, Giles and Catharine appear in Ann Arbor, boarding in the home of a travel agent named Joseph Irish. Giles, then working as a “Lecturer,” is worth $250.

In 1861, Catharine and Giles returned to Rochester, where Catharine gave birth to a son, George, who died the same day (Shotwell 220). In spite of the tragedy of losing two children so close together, Catharine, undaunted, then turned her focus to the exigencies of the Civil War. According to A Woman of the Century, she penned “short letters on the conduct of the war” to local newspapers in Rochester, stressing the urgency of securing freedom for the enslaved above and beyond preserving the Union (681-2). She also “entered zealously into General Fisk’s work of clothing refugees on the west of the Mississippi” (682). This refers to Clinton and Jeannette Fisk’s wartime relief efforts, to provide formerly enslaved refugees fleeing the South with basic necessities upon their arrival in free states (Brockett 711). The 1865 state census shows Catharine and Giles living Benjamin and Sarah's household in Gates, a Rochester suburb.

Susan B. Anthony notes that, by December 1865, “Giles and Kate Stebbins” visited their old friends, the Garrisons, in Boston (Gordon 560). Giles and Catharine then lived briefly as boarders in Washington, D.C., during 1867 and 1868 (Steps 112). By the end of 1868, they had set out once again for Michigan, settling this time in Detroit.

This move would be, more or less, a permanent one for the couple. Once in Detroit, Giles focused his attention on his various literary endeavors, in which he championed suffrage, spiritualism, and protectionism. Giles' anthology of world poetry, Poems of the Life Beyond and Within (1877), stands out as an affirmation of his personal belief in metaphysics. Some of the poems in the volume, however, seem to have no prior provenance, suggesting that Giles may have inserted some verses of his own creation and passed them off as ancient Arabic or Persian originals. Giles also published an autobiography in 1890, entitled Upward Steps of Seventy Years. The sprawling memoir captures Giles' friendships with great personages of the era, such as Garrison, Mott, and Douglass. It nevertheless contains scarce mention of Catharine, who is referred to laconically only as “Wife and myself” or “Mrs. Stebbins and myself” (65, 92, 112, 135, 138).

In the aftermath of the Civil War, a rift would emerge within the Suffrage Movement. Dissension now festered surrounding the prioritization of securing franchise for Black men in advance of White women. Catharine, like many Seneca Falls veterans, remained loyal to the cadre of leadership from New York State. This faction, headed by Stanton and Anthony, formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in 1869. Catharine and Giles still appeared to be open to the prospect of aisle-crossing. According to the second volume of the History of Woman Suffrage, they are recorded as being present at the inaugural meeting of the rival American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), held in Cleveland in November 1870 (2:759).

Catharine was also making good trouble back in Michigan around this time. In March 1871, she and Nannette B. Gardner, a fellow-traveller, attempted to register to vote in Detroit. In doing so, the pair contended that they, according to the language of the 14th Amendment, qualified "as persons." Their applications requesting to be added to voter rolls were appealed to Detroit's Board of Registration in their respective wards. At the hearing for Gardner, a motion to remove her name from the rolls was voted down. Catharine also received a hearing, at which, “when asked to submit her reasons for demanding the right to vote, Mrs. S. stated that she asked it simply as the right of a human being under constitution of the United States. She had paid taxes on personal and real estate, and had conformed to the laws of the land in every respect. Since the fourteenth amendment had enfranchised woman as well as the black man, she had the necessary qualification of an elector” (3:523). In Catharine's case, the Board of Registration was successful in redacting her name from the ward's voter roll.

Nannette Gardner managed to vote in Detroit in 1871 and again in 1872, becoming the first woman in the state of Michigan do so. Catharine and Giles proudly accompanied Gardner on her trip to the polls on election day. Catharine attempted to register and vote again the following year, but was again barred. Her exploits on behalf of winning franchise in Michigan appear in the third volume of History of Woman Suffrage, within a chapter on Michigan activies that she herself took the lead in compiling and drafting.

Catharine was present and took part in the discussion at an January 1875 convocation of the NWSA, the organization's seventh “Washington Convention” (2:583). Her involvement was cited in national media coverage, regarding the convention’s “prominent members” (“National”). In 1876, NWSA membership focused its efforts on being included in the Grant Administration’s celebration of the July 4th centennial in Philadelphia. Unsurprisingly, the NWSA old guard were denied inclusion in any official ceremony, so they commandeered a band stand in the vicinity of Independence Hall and held their own commemoration. A declaration was drafted and read on this occasion; Catharine was one of its signers (3: 32). The History of Woman Suffrage bemoans the fact that “Count Rochambeau of France, the Japanese commissioners, high officials from Russia and Prussia, from Austria, Spain, England, Turkey, representing the barbarism and semi-civilization of the day, found no difficulty securing recognition and places of honor upon that platform, where representative womanhood was denied” (29). Emissaries from monarchical governments around the world were given a place of honor at Grant's celebration, while patriotic American women demanding their civil liberties were excluded.

The Stebbinses used their time in Pennsylvania to drop in on Lucretia Mott, then staying with her adult children (Steps 136). Catharine and Giles again visited Mott in Rochester in 1878, trekking from Michigan for the 30th anniversary celebration of the Seneca Falls Convention (Steps 136). A March 1874 letter addressed to "My Dear Catharine" in Detroit, composed "Roadside near Philadelphia," contains Mott's reading recommendations and bits of family news, revealing an active warm, relationship between the two distant relatives.

In January 1880, Catharine spoke in Washington before the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives. She was part of a NWSA delegation arguing on behalf of what would then have been the 16th Amendment. Quoting Tennyson in her speech, she fiercely asserted, “’Better fifty years of Europe than a cycle of Cathay!’ So said the poet; and I say, 'Better a week with these inspired women in conference than years of an indifferent, conventional society'” (3:162). Her testimony also touted in the virtue of temperance and the evils of war. News of the NWSA delegation, with mention of Catharine's participation, was circulated nationally.

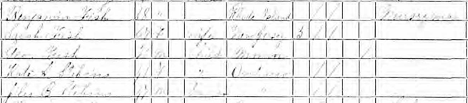

In 1880, Giles and Catharine, now 62 and 56, board in the home of Mrs. William Smith in Detroit. Giles is listed as a lecturer by profession; Catharine’s profession is given simply as “Boarding.”

Unable to attend the 1884 NWSA convention in Washington, Catharine sent a letter of encouragement, along with a donation of $60 dollars that she and her Michigan cohort had fundraised (NWSA 9, 134).

Unable to attend the 1884 NWSA convention in Washington, Catharine sent a letter of encouragement, along with a donation of $60 dollars that she and her Michigan cohort had fundraised (NWSA 9, 134).

The History of Woman Suffrage records Catharine, in 1887, leading a contingent of 16 suffragists to speak before the Judiciary Committee of the Michigan Legislature. At this time, she presented before committee a petition in favor of a municipal suffrage bill that had been introduced to both chambers (4:761).

In addition to her long-standing ties to NWSA, Catharine also served as a founding member of the Association for the Advancement of Women (AAW), headed by AWSA-affiliated suffragist Julia Ward Howe. The AAW was primarily dedicated to promoting women's progress in the fields of education and industry. Catharine gave a lecture on “Spurious and Adulterated Manufactures,” a topic somewhere in the vein of consumer protection, at the 1875 AAW meeting in Philadelphia. She is identified in conference programs as a director or vice president at AAW congresses in 1885 at Des Moines, 1886 at Louisville, 1887 at New York City, 1889 at Denver, 1890 at Toronto, and an 1891 mid-year conference at Washington, D.C.

In 1890, Giles is listed in a Detroit directory boarding at 335 Fort Street West (1034). Catharine, now entering her 70s, joined the Revising Committee of The Woman's Bible, a series of feminist commentaries on scripture. The text was ultimately adjudged to be quasi-heretical in its moment in time, earning infamy for the circle of authors who helped to create it, especially Stanton. In the volume, Catharine penned an editorial roundly defending her involvement. “The Bible,” she begins, “viewed by men as the infallible ‘Word of God,’ and translated and explained for ages by men only, tends to the subjection and degradation of women” (211). She describes the work at hand: “Here is ‘a reform’ not ‘against Nature,’ nor the facts of history, but is true to the Mother of the Race, to her knowledge of ‘the Word,’ to her desire to promulgate it, to her actual participation in declaring and proclaiming it” (211). In 1895, Catharine was counted among the well-wishers in attendance at Stanton’s 80th birthday party in New York City (“New Woman”).

In May 1896, the Michigan State Suffrage Association held a two-day convention in Pontiac, Michigan. Participants rejoiced in the fact that franchise had been won for women in places like Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Zealand, and Australia. A write-up of the meeting in The Pontiac Gazette notes, "A thrilling incident was the presentation to the assembly of the venerable Catherine A. F. Stebbins, with the explanation that she was a participator in the original convention held four-eight years ago, for securing legal rights to women" ("Equal"). Undeterred nearly one half-century after Seneca Falls, Catherine and Giles each gave speeches at the gathering.

By the time of the 1900 census, Giles and Catharine, 82 and 76, are listed as boarders in the home of a 40-year-old female Irish immigrant by the name of Shaughnessy. The 1900 census had the nerve to ask women how many children they had given birth and how many remained alive. Catharine dutifully responded to the first question with "2." Zero had survived by the time of the census.

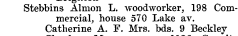

Giles Stebbins passed away on Halloween, 1900, in Detroit. “Old Age” is listed as the instigating cause on his death certificate. After her husband's death, Catharine appears to have returned briefly to the old familiarity of Rochester. A 1903 Rochester city directory places her boarding at 9 Beckley (740).

On November 8, 1904, Signer #11 passed away. She is buried in a family plot near her parents, spouse, and children in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester (“Catherine Ann Fish Stebbins”). It is unclear how Catharine and Giles first became acquainted. Perhaps they met at the Sodus Bay Phalanx, both drawn to its Fourierist promises of a utopia of civil equality and amorous freedom. While they each pursed their own respective utopian enterprises in life, Catharine's and Giles' political and theological philosophies appear to have been thoroughly aligned.

Catharine Fish Stebbins lived a life verging on asceticism, as she criss-crossed the country, fighting the good fight. A renter for the majority of her adult life, Catharine defies a generalization that suffragists were automatically well-heeled and dying of boredom. Her commitments to the NWSA and AAW would have meant a staggering amount of travel, time, and expense. Come hell or high water, Signer #11 stuck with cause for her entire life.

Works Cited

“Another Woman’s Rights’ Convention.” The Daily Crescent (New Orleans), 17 Aug. 1848, p. 3.

Association for the Advancement of Women. Papers Read before the Association for the Advancement of Women. 1892.

“Benjamin Fish.” Freethought Trail, Accessed 11 Nov. 2022. https://freethought-trail.org/profiles/profile:fish-benjamin/

Brockett, Linus Pierpont. Woman’s Work in the Civil War: A Record of Heroism, Patriotism and Patience. Zeigler, McCurdy & Company, 1867.

“Catherine Ann Fish Stebbins.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 11 Nov. 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/76527390/catherine-ann-stebbins

Daily American Directory of the City of Rochester. Jerome & Brother, 1847.

Detroit City Directory for 1890. Polk, 1890.

Douglass, Frederick. The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, from 1817-1882. 1882.

---. The Frederick Douglass Papers: Series Three, Correspondence, Volume 1: 1842-1852. Yale University Press, 2009.

"Equal Suffrage." Pontiac Gazette (Michigan), 22 May 1896, p. 10.

“Female Suffrage.” The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), 24 Jan. 1880, p.1.

“The First New Woman.” Johnstown Daily Republican, 13 Nov. 1895, p. 6.

“Fish Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Rochester, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 11 Nov. 2022.

“Fish Household.” New York State Census, 1865. Gates, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 11 Nov. 2022.

“Giles Stebbins—Death Certificate.” Michigan Department of State, Detroit, Wayne County. Ancestry.com, Accessed 11 Nov. 2022.

Gordon, Anne Dexter. The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Rutgers University Press, 1997.

Greenlee, Ralph S. and Robert L. Greenlee. The Stebbins Genealogy. Self-published, 1904.

Hazard, Thomas. Mediums and Mediumship. William White & Company, 1873.

History of Woman Suffrage: Volume I, 1848-1861. Ayer Company, 1881.

History of Woman Suffrage: Volume II, 1861-1876. Susan B. Anthony, 1881.

History of Woman Suffrage: Volume III, 1876-1885. Fowler & Wells, 1886.

History of Woman Suffrage: Volume IV, 1883-1900. Susan B. Anthony, 1902.

“Irish Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Ann Arbor, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 11 Nov. 2022.

Kesten, Seymour R. Utopian Episodes: Daily Life in Experimental Colonies Dedicated to Changing the World. Syracuse University Press, 1996.

Michigan Legislature, House of Representatives. Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan. 1887.

Mott, Lucretia. "Letter to Catharine Stebbins." TriCollege Libraries Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/object/sc161273#page/3/mode/1up, Accessed 11 Nov. 2022.

“National Woman Suffrage Convention.” Smyrna Times (Smyrna, Delaware), 20 Jan, 1875, p.1.

National Woman Suffrage Association. Report of the Annual Washington Convention. National Woman Suffrage Association, 1884.

Noyes, John Humphrey. History of American Socialisms. J.B. Lippincott & Company, 1870.

“Obituary—Mary Wendelline Stebbins.” The Anti-Slavery Bugle, 7 Jan. 1860, p. 2.

Parker, Jenny Marsh. Rochester: A Story Historical. Scrantom, Wetmore, 1884.

Report of the Woman's Rights Convention, 1848. University of Rochester, Special Collections, Accessed 11 Nov. 2022. https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/2448

Rochester Directory for the Year Beginning July 1, 1903. Sampson and Murdock, 1903.

“Shaughnessy Household.” Federal Census, 1900. Detroit, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 11 Nov. 2022.

Shotwell, Ambrose Milton. Annals of Our Colonial Ancestors and Their Descendants; or, Our Quaker Forefathers and Their Posterity. R. Smith, 1897.

"A Sixteenth Amendment.” The New Northwest (Portland, Oregon), 25 Mar. 1880, p. 2,

“Smith Household.” Federal Census, 1880. Detroit, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 11 Nov. 2022.

Stebbins, Catharine. “Letter to William Lloyd Garrison-April 1852.” Digital Commonwealth: Massachusetts Collections Online, Accessed 6 Dec. 2022. https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:2v23x555p

---. “Letter to William Lloyd Garrison-September 1854.” Digital Commonwealth: Massachusetts Collections Online, Accessed 6 Dec. 2022. https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:2v23xb77r

---. “Letter to William Lloyd Garrison-January 1860.” Digital Commonwealth: Massachusetts Collections Online, Accessed 6 Dec. 2022. https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:5h740t62f

Stebbins, Giles Badger. “Letter to W.H. Siebert.” Ohio History Connection, Accessed 6 Dec. 2022. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/siebert/id/26592/.

---. Poems of the Life Beyond and Within. Colby and Rich, 1877.

---. Upward Steps of Seventy Years: Autobiographic, Biographic, Historic. United States Book Company, 1890.

Transactions of the N.Y. State Agricultural Society. New York State Legislature, 1852

Willard, Frances Elizabeth, and Mary Ashton Livermore. A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-Seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life. Moulton, 1893.

The Woman’s Bible. European Publishing Company, 1895.

“Woman’s Rights.” The Polynesian (Honolulu, Hawaii), 3 Mar. 1849, p. 2.