Signer #3: Margaret Pryor, "The Utopian"

Signer #3: Margaret Wilson Pryor

Born: 1784, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Died: February 20, 1874, Landis, New Jersey, Age 89

Occupation(s): Educator, Activist, “Keeping House”

Local Residence: Virginia Street, Waterloo

Special thanks to Grace Roper and Lorie Dalola for the research undertaken in the production of this piece.

Not all utopias are destined to be winners.

Communal experimentation was all the rage in the Burned Over District of the 1840s. Communards often found themselves forced to improvise modes of interpersonal harmony within fragile, newly formed social collectives. One potent source of guidance in this respect was the utopian socialism of François Marie Charles Fourier. Many of the communes that sprang up in the vicinity of Seneca Falls before 1848 attempted some approximation of Fourier’s ideal social model, the Phalanx. Getting down to the finer points of the philosopher's sometimes convoluted directives, however, represented a unique challenge. As much as the well-intentioned soul might wish it, the labor of building utopia was fraught with difficulties, both internal and external.

Margaret Wilson Pryor, Signer #3, and her spouse, George Pryor (#93), affiliated with two very different intentional communities during their 50 years of married life together. With each communal endeavor separated from the other by almost two decades, the Pryors' attempts at utopia met with varying degrees of success.

Beyond being a disenchanted communard, Margaret Pryor stands out as something of an elder stateswoman at the Seneca Falls Convention. In July 1848, she was about 63 years old and, already, an experienced educator, a seasoned veteran of the Anti-Slavery Movement, and Hicksite Quaker. She would later be remembered by Elizabeth Cady Stanton (#4) as having “sustained the demand for woman suffrage with earnest sympathy” (History 477).

Margaret Wilson was born in 1784 to a Quaker household in Philadelphia. Her mother was named Sarah, a detail captured only in the record of Margaret’s 1816 wedding. Margaret’s father, John Wilson, worked as a boatbuilder. He achieved notoriety for constructing one of the earliest functional steamboats, based on a design produced by inventor John Fitch (Cope 100). According to an 1899 article appearing in The Literary Era, Wilson’s account book, then in the possession of descendants, contains details regarding Fitch’s commission of a 45-foot steamboat, to be assembled by Wilson in November 1786 (41). By 1788, one of Fitch’s crafts completed a voyage of 20 miles, traveling by steam from Philadelphia to Burlington, New Jersey. The trip was, at the time, the greatest distance ever covered by any steamship. The successful collaboration between Fitch and Wilson occurred well in advance of Robert’s Fulton’s steamboat Clermont, which went operational in 1809 (“Robert Fulton”).

Margaret’s mother passed away sometime prior to 1791. In May of that year, John Wilson married Elizabeth Pyle. Signer #6, Mary Ann McClintock (née Wilson), was born in 1800, the daughter of Elizabeth and John (Cope 99). Margaret and Mary Ann, half-sisters, would remain closely attached to each other for the rest of their lives, never venturing too far apart for too long.

At the approximate age of 32, Margaret married George Pryor in Burlington, New Jersey, on November 14, 1816. This was George Pryor’s second marriage, and he brought a daughter, Sarah Ann, to the union (“Pryor-Margaret Wilson Marriage”).

Quaker records indicate that the Pryors moved to Jefferson County, New York, around the year 1819 (“Sarah Ann Pryor”). A son, George W. Pryor, was born in 1820 while the family resided at Cape Vincent, where George labored as a carpenter. By 1828, Margaret and George were hired on as wards of the “boarding department” at a school in nearby Lowville, Lewis County (Andrews 38). I take this to mean that the Pryors’ vocation was analogous to directing residential life for boarders at the institution.

The Pryors resurface in 1835 at Skaneateles, Onondaga County, promoting a co-educational boarding school that they had founded. An advertisement taken out in The Skaneateles Columbian claims that "The New Hive" affords matriculants scenic views of the lake and easy access to the village. The school, it adds, offers “one of the most pleasant and healthful situations in the Union.” Tuition is set at $25 per quarter with a curriculum steeped in Greek, Latin, French, and mathematics. At Skaneateles, the couple would affiliate with the Scipio Monthly Meeting (Wellman 94).

Margaret’s budding career in education did not prevent her from becoming involved in a radical communitarian enterprise. Alongside brother-in-law Thomas McClintock (#86), Margaret is named among a group of stakeholders, inviting outsiders to a convocation that would resolve all of society’s ills. A call published in The Skaneateles Columbian welcomes the general public to a "Convention” to be held at the Skaneateles Community, located on a 300-acre tract in the vicinity of the village. “The object of this gathering is not to labor especially for the benefit of any particular class, but for the entire race—not to concentrate our efforts upon any one manifestation of evil, but to remove the source of all our social discord—not merely to contend with effects, but to battle against causes. Men every where sustain false relations. Society is based upon antagonisms,” it complains. The planned dialogue would, ideally, determine some means of resolving racial and class division in the United States.

Margaret’s budding career in education did not prevent her from becoming involved in a radical communitarian enterprise. Alongside brother-in-law Thomas McClintock (#86), Margaret is named among a group of stakeholders, inviting outsiders to a convocation that would resolve all of society’s ills. A call published in The Skaneateles Columbian welcomes the general public to a "Convention” to be held at the Skaneateles Community, located on a 300-acre tract in the vicinity of the village. “The object of this gathering is not to labor especially for the benefit of any particular class, but for the entire race—not to concentrate our efforts upon any one manifestation of evil, but to remove the source of all our social discord—not merely to contend with effects, but to battle against causes. Men every where sustain false relations. Society is based upon antagonisms,” it complains. The planned dialogue would, ideally, determine some means of resolving racial and class division in the United States.

The Skaneateles Community, inaugurated in October 1843, was inspired by Fourierist thinking, and, despite its ambitions toward racial and gender equality, it would encounter some of the typical impediments that plague communes. Co-founder John Anderson Collins would fashion himself as patriarch of the group, instituting a code of behavior that many participants found too extreme. Collins’ pro-Fourierist mandates regarding polyamory, atheism, anarchy, and vegetarianism did not sit well with several members of the Community (“Skaneateles Community”).

Whatever initial enthusiasm they might have felt, Margaret and George counted among the earliest departures from Collins’ doomed utopia. The Pryors disaffiliated in protest from the Skaneateles Community after witnessing other communards playing cards and enjoying music. The commune would be completely dissolved in 1846 (Hamm 156-7). The Pryors’ short-lived involvement in this enterprise parallels that of Catharine Fish Stebbins (#11) and Azaliah Schooley (#100). Stebbins and Schooley each married their respective spouses at the equally ephemeral Sodus Bay Phalanx, located on the shores of Lake Ontario.

In 1838, The Pryors relocated to Waterloo, Seneca County (Andrews 38). The couple settled at a residence on Virginia Street and became affiliated with the Junius Monthly Meeting (Wellman and Warren 20, 105). George Pryor appears as head of household in the 1840 census for Waterloo. He and an individual inferred to be Margaret live with four unidentified adolescents.

In 1838, The Pryors relocated to Waterloo, Seneca County (Andrews 38). The couple settled at a residence on Virginia Street and became affiliated with the Junius Monthly Meeting (Wellman and Warren 20, 105). George Pryor appears as head of household in the 1840 census for Waterloo. He and an individual inferred to be Margaret live with four unidentified adolescents.

It was around this same time that Margaret and George became deeply invested in the early stirrings of the Anti-Slavery Movement. Anne Dexter Gordon notes that Margaret attended a women’s antislavery convention in 1837 (n45). Both Margaret and George attended the first meeting of the Garrisonian Western New York Anti-Slavery Society, held in 1839 at Penn Yan (Wellman & Warren 17). Margaret served on the organization's executive committee (Wellman 113).

Through these engagements with Abolitionism, Margaret first met activist and orator Abby Kelley. Kelley, in fact, would enlist Margaret as a kind of chaperone and bodyguard, as the former occasionally faced down unsupportive and unruly audiences. Elizabeth Cady Stanton remembers that Kelley, then in her late 20s and early 30s, “was a young girl, speaking through New York in the height of the anti-slavery mobs…Margaret Pryor traveled with her for company and protection. Abby used to say she always felt safe when she could see Margaret Pryor’s Quaker bonnet” (History 477). Kelley would seek out Margaret’s “honest almost angel face” whenever confronted by a scowling, hostile crowd of reactionaries (quoted in Sterling 166). Beyond offering moral support, Margaret also worked the room by collecting subscriptions for The Anti-Slavery Standard during Kelley’s speeches (Sterling 164). As explored in the profile of Delia Mathews (#14), the outrage felt in Seneca Falls after a speaking engagement by Kelley was more than enough to foment a community-wide scandal.

Margaret had also, at some point in the early 1840s, become an acquaintance of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. In a February 1843 letter addressed to Elizabeth J. Neall, Stanton asks that Neall “remember me kindly to…Mrs. Prior [sic]” (quoted in Gordon 42). Through their friendship, Margaret would introduce Stanton to Amelia Willard sometime between 1847 and 1851. Pryor had personally trained Willard, who would work in the capacity of housekeeper and nanny in Stanton’s household for 30 years. Stanton considered Willard an indispensable assest in the proper functioning of her household (Gordon n. 45, Petravage 14). A footnote added by Stanton in the third volume of The History of Woman Suffrage praises Willard as a “splendid housekeeper.” Many of Stanton’s own accomplishments would have been impossible without Willard’s “untiring and unselfish services” (477). In the Declaration of Sentiments, Margaret’s signature appears after that of Stanton’s sister Harriet Cady Eaton (#2) and immediately before Stanton’s own. These ordinal proximities hint at the social bonds that had been formed between the Stantons and Pryors.

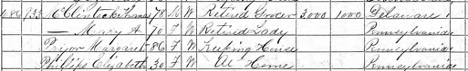

In an 1850 census record for Waterloo taken by Isaac Fuller, Margaret, 65, and George, a farmer of 70, appear in a household with a slew of non-relations.

Under the same roof, 5 males in their 20s reside, with their vocations ranging from woolsorter, to merchant-tailor, and law student. There are also 3 females, aged from 13 to 26. This includes Matilda Ray or Rany, a 17-year-old Black woman from New York (Wellman and Warren 6). Judging by the makeup of the residence, the Pryors might have utilize their home as a boarding house.

The Pryors were also then becoming involved in the group known, alternately, as the Congregational Friends, the Progressive Friends, and, after 1855, the Friends of Human Progress. This cadre had broken off from the main body of Quakers in order to better suit their progressive stance on racial justice and women’s rights. The yearly meeting of the Congregational Friends for 1849 was held in Waterloo. In published minutes of the gathering, Margaret has been appointed to two committees, one tasked with organizing “a future sitting,” and the other with outreach and correspondence with any sympathetic parties (3, 9). Other signers of the Declaration appointed to just these same two committees include Mary Ann M’Clintock, Margaret Schooley (#7), Rhode Palmer De Garmo (#48), Susan Doty (#53), Richard P. Hunt (#69), William Barker (#77), William S. Dell (#80), and Azaliah Schooley (#100). C. De B. Mills later recalled traveling to Waterloo in 1856 for the meeting of the Friends of Human Progress. Mills lodged with “Uncle George and Aunt Margaret…as they were called” during the visit (50). Like-minded notables attracted to the meetings of the Friends of Human Progress included Lucretia Mott (#1), Isaac and Amy Post (#10), Lucy Colman, Frederick Douglass (#73), Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, and Stanton (Dean 52). The Proceedings of the Yearly Meeting of Friends of Human Progress, held again at Waterloo in 1859, does mention that a George Pryor, now hailing from Auburn, spoke at the meeting (15). This is the last indication of the Pryors residing in New York that I could locate.

Margaret and George appear next in Landis Township, New Jersey, in June 1863. The couple has affixed their signatures to a communal Temperance pledge. By signing, they vow to make their new community, Vineland, “the home of sobriety, of virtue, of good order, of good morals, and of temporal prosperity.” In this, “our infant settlement,” they foreswear the sale and personal consumption of alcohol (quoted in Andrews 8). As explored in the profile of David Spaulding (#76), it appears that a number of signers left New York in their golden years to be a part of this pilot community.

Vineland was the brainchild of Charles Landis, who had conceived of it with more-modest utopian aims than what had motivated the Skaneateles Community. Landis first sold parcels of Vineland to prospective communards in 1861, and construction had begun in February 1863 (Elmer 86). A strict teetotaler, Landis devised a law stating that, locally, “no ale, porter, beer, or other malt liquor shall be sold as a beverage” unless an establishment was granted a license to do so (87). Any such license required the approval, by popular referendum, of Vineland’s citizenry. By 1869, no approval had been voted affirmatively.

Famously, Vinelandian dentist and minister Dr. Thomas Bramwell Welch, in keeping with the community injunctions against alcohol, pioneered the technique of pasteurizing grape juice in order to prevent its fermentation into wine. The alcohol-free beverage could then be incorporated into church communion services. Welch’s innovation would eventually become the Welch’s Juice brand (DiUlio). In spite of its strict prohibition on intoxicating spirits, the Vineland community did encourage personal property (an allowance that Fourier would have scoffed at). Vinelandians could purchase their own private homes on the community’s neatly manicured thoroughfares.

In the modified, semi-communal life of Vineland, Signer #3 seems to have found a home. According to the 1918 edition of Vineland Historical Magazine, the Pryors celebrated their golden anniversary at their Vine Street home on November 14, 1866. Margaret’s half-sister, Mary Ann McClintock, had the special distinction of having been present at both George and Margaret’s wedding 50 years earlier and at their anniversary party. George Pryor died the following month, in December 1866 (39).

George’s passing in no way dampened Margaret’s spirit for activism. The third volume of The History of Woman Suffrage includes an anecdote from Vinelandian Elizabeth A. Kingsbury. Kingsbury had been part of a contingent of the community's women, including Margaret, who attempted to vote in the national election on November 5, 1868.

Arriving at their local polling place, the group presented their completed ballots at the dropbox. These were summarily “rejected with politeness” by registrars on hand. The same ballots were then deposited in an unofficial ballot box. Kingsbury describes the makeshift receptacle: “Shall I describe this box, twelve inches long and six wide, and originally a grape-box?” Kingsbury observes, addressing Stanton, that the party included “Margaret Pryor, who is better known to you perhaps than many of your readers, as one whose life has been active in the cause of freedom for the negro and for woman; a charming old lady of eighty-four years, yet with the spirit, elasticity and strength of one of thirty-five…there in her nice Quaker bonnet." Her presence was "a great part of the day” (477). Recounting other details of election day, Kingsbury reports that Vineland’s women voted in shifts, so that a portion could stay behind, taking “care of the babies while the mothers come out to vote. Will this fact lessen the alarm of some men for the safety of the babies of enfranchised women on election day?” (477). U.S. Grant carried the women's mock-vote for president with 164 votes, but 2 votes cast on the day were for Elizabeth Cady Stanton (478).

In the 1870 census, Margaret is recorded “Keeping House” in the Landis residence of Thomas and Mary Ann McClintock.

Margaret Pryor, Signer #3, passed away on February 20, 1874, at age 89. Her cause of death is listed officially as “Paralysis.”

Margaret is interred next to husband at Siloam Cemetery in Vineland.

As much as the well-meaning soul might desire it, the work of assembling an ideal community is fraught with hardship. Subordinating some portion of one's self-possession and personal space for the good of the many must have required a good deal of sacrifice. The oversized demands of a commune’s de facto patriarch also frequently served as a source of conflict.

The intentional communities of the 1840s were overwhelmingly destined to fail. Most did so within a matter of years. Notwithstanding this, these experiments impacted American culture in unique ways. Failed utopias also had an important impact on their disillusioned communards as well. The life of Margaret Pryor reveals that signers of the Declaration of Sentiments sought to occupy small slices of utopia on earth. At the same time, they still agitated vociferously against the ills of society in the public sphere.

Works Cited

Andrews, Frank. The Beginning of the Temperance Movement in Vineland. 1911.

“Community Convention.” The Skaneateles Columbian, 1843. Fulton History, www.fultonhistory.com. Accessed 20 Mar. 2023.

Cope, Gilbert. Genealogy of the Darlington Family: A Record of the Descendants of Abraham Darlington of Birmingham. West Chester, Pa. Self-published, 1900.

Dean, Phebe. “Letter From Phebe B. Dean.” Free Thought Magazine, vol. 12, 1895, pp.51-3.

DiUlio, Nick. “150 Years Ago, Vineland Was a Budding Utopia in South Jersey.” www.NJmonthly.com. https://njmonthly.com/articles/jersey-living/visionary-vineland/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

Elmer, Lucius Quintius Cincinnatus. History of the Early Settlement and Progress of Cumberland County, New Jersey. G.F. Nixon, 1869.

“George Pryor.” Vineland Historical Magazine, vol. 3, no. 2, April 1918, pp. 38-9.

“George Pryor-Margaret Wilson Marriage.” Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records. Ancestry.com, Accessed 19 Mar. 2023.

“George Pryor-Margaret Wilson Marriage.” Quaker Meeting Records, Burlington Monthly Meeting (New Jersey). Ancestry.com, Accessed 19 Mar. 2023.

Gordon, Anne Dexter. The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Rutgers University Press, 1997.

Hamm, Thomas D. God’s Government Begun: The Society for Universal Inquiry and Reform, 1842-1846. Indiana University Press, 1995.

History of Woman Suffrage: Volume III, 1876-1885. Fowler & Wells, 1886.

“A List of Early Diaries, Journals, Etc.” The Literary Era, vol. 6, no. 1, January 1899, p. 61.

“Margaret Pryor." Return of Deaths, Landis Township, Cumberland County, New Jersey, 1873-4. Ancestry.com, Accessed 19 Mar. 2023.

“Margaret Pryor.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 19 Mar. 2023.https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/183060694/margaret-pryor.

“McClintock Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Landis Township, Cumberland County, New Jersey. Ancestry.com, Accessed 19 Mar. 2023.

Mills, C.D.B., “By C. De B. Mills.” Free Thought Magazine. Vol. 12, 1895. pp.50-1.

“The New Hive Boarding School.” The Skaneateles Columbian, 1835, Fulton History, www.fultonhistory.com. Accessed 20 Mar. 2023.

Petravage, Carol. McClintock House, First Wesleyan Methodist Church and Stanton House. National Park Service, 1989.

Proceedings of the Yearly Meeting of the Congregational Friends, Held at Waterloo, Seneca Co. N.Y. Oliphant, 1849.

Proceedings of the Yearly Meeting of Friends of Human Progress, Held at Waterloo, Seneca Co. N.Y. Hebard, 1859.

"Pryor Household.” Federal Census, 1840. Waterloo, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 19 Mar. 2023.

“Pryor Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Waterloo, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 19 Mar. 2023.

“Robert Fulton.” Appletons Cyclopaedia of American Biography. Eds. James Wilson and John Fiske, vol. 2, 1888, pp. 563-4.

“Sarah Ann Pryor.” Quaker Meeting Records, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting (Pennsylvania). Ancestry.com, Accessed 19 Mar. 2023.

“Skaneateles Community.” Freethought Trail, https://freethought-trail.org/trail-map/location:skaneateles-community/. Accessed 8 Mar. 2023.

Sterling, Dorothy. Ahead of Her Time: Abby Kelley and the Politics of Antislavery. W. W. Norton & Company, 1994.

Wellman, Judith, and Tanya Warren. Discovering the Underground Railroad, Abolitionism and African American Life in Seneca County, New York, 1820-1880. Seneca County, 2006.

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman’s Rights Convention. University of Illinois Press, 2010.