Signer #58, Lavinia Latham: “Susan B. Anthony's Grave"

Signer #58: Lovina Janes Latham

Born: June 26, 1781, Coventry, Connecticut

Died: January 21, 1859, Seneca Falls, age 77

Local Residence: 37 West Bayard Street, Seneca Falls

Since 2014, the grave of Susan B. Anthony has become the centerpiece of an Election Day ritual in America. After heading to the polls, voters affix their “I Voted” stickers onto Anthony’s headstone, located at Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester (Blakemore). The event has become so well attended that it regularly receives national media coverage. Cemetery caretakers welcome the stickers, but a clear, plastic shield has been placed over Anthony’s monument to protect its marble. The “I Voted” stickers have even made their way onto the tombstone of Susan’s sister, Mary Stafford Anthony (“Anthony’s”).

The truth is that improvised ceremonies at Susan B. Anthony’s gravesite are nothing new. They have actually been occurring for more than a century—just, minus the stickers. On July 20, 1923, a delegation of the National Women’s Party (NWP) incorporated a visit to Mount Hope into their celebration of the 75th anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention. The weekend of events was not without a political objective. The organization was then poised to rollout its initial draft of the Equal Rights Amendment, co-authored by NWP leaders Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman.

The anniversary happenings began in Seneca Falls with a tribute that included local officials and a number of Convention descendants. According to The New York Evening Post, “Many of the leading citizens of the town taking part in the reception were grandsons and granddaughters of the little group of pioneers who held the first women’s rights convention in the same town in ’48.” On the next day, “the convention will make a pilgrimage to the grave of Susan B. Anthony” and “carry wreaths with parchment inscriptions to place on the grave of the great leader” (“Drafting”). At the wreath-laying, an organization of Black professional women offered a scroll bearing the following dedication: “We celebrate you as one of those early friends who faced the violence of the mob for the sake of freedom for our race” (“Woman Voter”).

Also scheduled for the anniversary weekend was an “exhibit of equal rights heirlooms contributed by local descendants of the suffrage pioneers,” put on view at the Lyceum Hall in Rochester (“Woman Voter”). The Oakland Tribune reports that the exhibition was to include "a copy of the ‘Lilly,’ the paper published by Amelia Bloomer…the desk, and chair of Elizabeth Cady Staton” and “the chair in which Susan B. Anthony is reputed to have rocked the Stanton babies while Mrs. Stanton wrote inspiring Suffrage speeches.” The Tribune adds, “Alice E. Pollard, great-granddaughter of Lovina Latham, a signer of the 1848 declaration of sentiments, arranged the display” (“Delegates”).

The passing mention, as brief as it is, provides a vital clue regarding the identity of Signer #58. First and foremost, it clarifies the spelling of her name. John Dick's Report of the Woman's Rights Convention from 1848 identifies signer #58 as “Lavinia Latham” (11). Produced at the offices of The North Star 50 miles away in Rochester, “Lavinia” most likely represents a misread transcription of Signer #58's signature. Local and familial sources (like Pollard) consistently render her name as “Lovina” and, less often, as “Lavina.”

Lovina Janes Latham appears in Frederic Janes’ 1868 genealogy, The Janes Family. The eighth child of her father's second marriage, Lovina was born in Coventry, Connecticut, on June 26, 1781, to Elisha Janes and Desire Thompson Janes (136). Lovina’s paternal aunt, Bathsheba Janes Tilden was the grandmother of Samuel J. Tilden, a future New York governor and presidential candidate (113).

Lovina married Obadiah Latham of Groton, Connecticut, on August 4, 1804. The couple soon migrated to New York State, settling in Paris, Oneida County, at some point prior to 1806. They resided at Paris until at least 1820, and ten of their eleven children were born there: Adelia in 1806, Benjamin Franklin (or Franklin B.) in 1807, Edward in 1808, Hannah Janes in 1810, Esther in 1811, William Harrison in 1813, Oliver Sandford in 1816, Mary in 1817, Susan Lovina in 1819, Obadiah in 1820, and Nathaniel in 1822 (Wellman & Warren 665, Janes 189-190). Lovina's daughter Hannah J. Latham would become Signer #67 of the Declaration.

According to payroll abstracts, Obadiah served in the New York State Militia during the War of 1812, eventually rising to a captaincy in the 134th Regiment. For reasons unknown, he deserted his post in October 1814. In 1901, the New York State historian would reproduce an officer’s frustrated communiques pertaining to this event. Brigadier General Oliver Collins would report from Sackett’s Harbor, “I am extremely mortified that I am obliged to report to your Excellency Captain Obadiah Latham and Lieutenant Albion Smith…as having disgraced their commissions by deserting their companies at this post. They practiced a shameful deception on me, by feigning ill-health and requesting a pass to get by the picket to enjoy fresh air which I granted, with an express order to return the same day. Instead of obeying the order they packed up and left the camp altogether and took with them two soldiers.” Dispatching an officer to arrest them at Watertown, Collins discovered that they had supplied false information regarding their whereabouts. He complained to his superior that “they have eluded my pursuit and prevented a trial—all I can do now is to leave them to the disposal of your Excellency” (qtd. in Hastings 1538). It is unclear how common or uncommon militia desertions of this type were during the conflict.

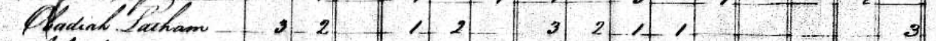

Obadiah appears as head of a 15-person household in the 1820 census for Paris, Oneida County.

With Alice E. Pollard serving as an informant, Dr. Frederick Lester’s 1936 account of the Latham family explains Lovina’s and Obadiah’s relocation to Seneca Falls. Obadiah supported the family as a “contractor and builder” (173). In the 1820s, he was recruited by an entrepreneur, Eleazar Hills, to oversee the construction of the village's water-powered mills along the Seneca River (172).

The Lathams established a homestead on Bayard Street. This tract would become the site of a number of the extended family’s homes in the coming decades (Wellman and Warren 188). The Lathams attended Trinity Episcopal Church on East Bayard Street (Wellman and Warren 227, Shaw).

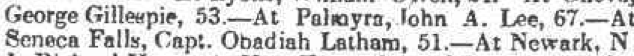

Obadiah died of typhoid fever on October 1, 1831, aged 51 (Lester 173).The New-York Spectator makes mention of this: “At Seneca Falls, Capt. Obadiah Latham, 51” (“Died”). Elsewhere, records of Obadiah’s passing remark that he died “leaving a very large family” (qtd. in Bowman 144). Frederick Lester reports that, by 1936, Obadiah’s carpentry toolbox still remained in the possession of Latham descendants (171).

Lovina would come to reside at 37 West Bayard Street (Gable 17). The 1840 census for Seneca Falls lists her as head of household, residing with two unidentified males between the ages of 15 and 20 and two unidentified females, aged 20 to 30.

Seventeen years a widow, Lovina had just turned 67 by the time of the Seneca Falls Convention. She is one of several widowed signers of the Declaration of Sentiments, a list that includes Lydia Mount (#13) and the best candidates for Phebe King (#35) and Betsey Tewksbury (#47). This presence might reflect the dire economic prospects that widowed women faced at this point in American history, especially in the nation's perilous frontier zones. It could also be a consequence of the limited legal privileges that law then affored widows, including property ownership and separate economy.

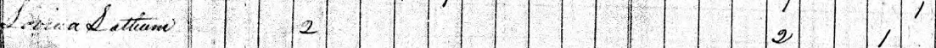

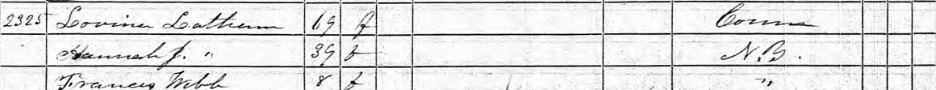

In an October 1850 census record set down by Isaac Fuller, Lovina, aged 69, appears residing with her 39-year-old daughter, Hannah J. Latham. There is also an eight-year-old girl, Frances Webb.

Frances is Lovina’s granddaughter, the child of Mary E. Latham and William Webb (Janes 190). Mary Webb died on December 24, 1848, and Frances had been absorbed into Lovina’s household (Wellman & Warren 665).

Lovina Latham died January 21, 1859, at age 77 (Janes 189). Her daughter Hannah J. Latham passed away only four days later. The proximity of their deaths in wintertime suggests that contagious disease took their lives. As Judith Wellman and Tanya Warren point out, Lovina was the matriarch of what became “one of the key reform families in Seneca Falls, both for abolitionism and woman’s rights” (185). According to Walt Gable, five Latham sons and two daughters remained in Seneca Falls and became prominent citizens of the town (14). Their lives, careers, and activism will be explored in the profile for Hannah J. Latham.

The organizer of the 1923 exhibition at Lyceum Hall, Alice E. Pollard was a descendant of Lovina's youngest child, Nathaniel (Jackson & Jackson 27). Alice Pollard attended Cornell, graduating Phi Beta Kappa, and worked as a high school educator. She resided in Seneca Falls up to the time of her death in 1960, at age 77. She, too, is interred at Restvale Cemetery (“Pollard”). Pollard's effort to showcase historical artifacts connected to Seneca Falls is proof that signers’ descendants took an active role in preserving and memorializing the legacy of their forebearers.

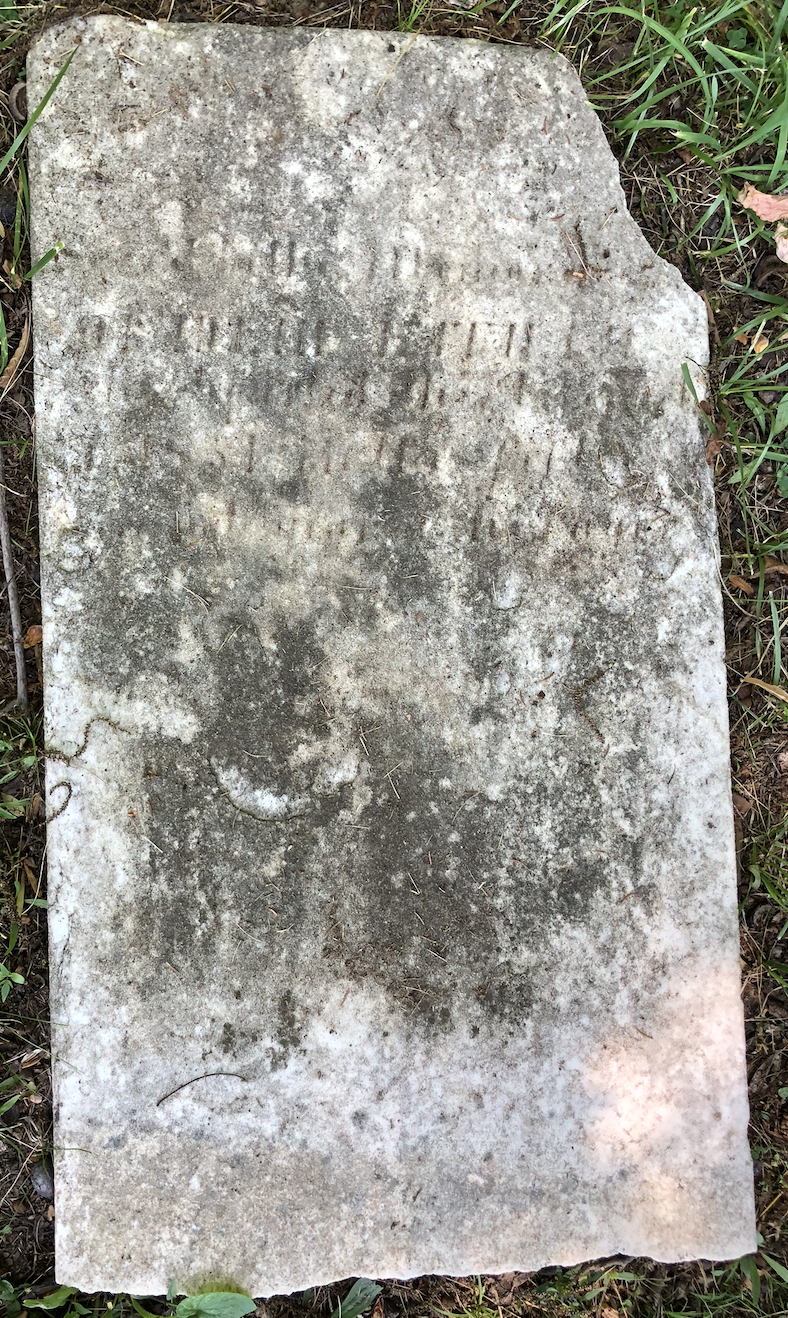

The location of Lovina Latham’s final resting place is currently unknown. An obvious lead is her spouse’s gravesite at Restvale Cemetery, even though their deaths were separated by nearly three decades. A tombstone for Obadiah Latham, which signifies his service in the War of 1812, is located at Restvale Cemetery (“Obadiah Latham”). It is part of a large family plot that contains at least three generations of Lathams, including Lovina's children and grandchildren.

These tombstones, denoting military service, appear to have been placed at burial sites belatedly, some time after the American Civil War. A visit to Restvale during the summer of 2025 revealed that another, older headstone for Obediah Latham exists. Its base had broken at some point, and the memorial had fallen over, leaving its inscription exposed to direct weathering. The name "Obediah Latham" can barely be made out, along with the year "1831." The rest of the lettering is too difficult to make out. These lines could contain crucial information about the burial location of Signer #58, but they have been lost to time and the elements.

The marked contrast between the graves of Susan B. Anthony and that of Lovina Latham is illustrative of the many gaps in the historical record of the American Suffrage Movement. Anthony’s headstone is lavished with stickers every Election Day. At the same time, Lovina Latham’s final resting place still remains an utter mystery. If you manage to find Signer #58's tombstone, please affix your “I Voted” sticker to it.

Works Cited

“Alice E. Pollard.” The Geneva Times, 10 Mar. 1960, p. 30.

Blakemore, Erin. “Why Women Bring Their ‘I Voted’ Stickers to Susan B. Anthony’s Grave." Smithsonian Magazine, Accessed 25 May 2025. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-women-bring-their-i-voted-stickers-susan-b-anthonys-grave-180958847/.

Bowman, Fred. 10,000 Vital Records of Western New York, 1809-1850. Genealogical Publishing, 1985.

“Delegates to Visit Grave of Susan Anthony.” The Oakland Tribune, 22 July 1923, p. 4-S.

“Died.” The New-York Spectator, 19 Oct. 1831, p. 1.

Hastings, Hugh. Military Minutes of the Council of Appointment of the State of New York, 1783-1821. Vol. 2. State of New York, 1901.

Gable, Walt. Seneca County, NY: A Hotbed of Underground Railroad Activism, Accessed 25 May 2025. https://www.senecacountyny.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/10-10-19-Underground-Railroad-in-Seneca-County_ADA.pdf.

Jackson, Mary Smith, and Edward F. Jackson. Marriage and Death Notices from Seneca County, New York Newspapers, 1817-1885. Heritage Books, 1997.

Janes, Frederic. The Janes Family. Dingman, 1868.

“Latham Household.” Federal Census, 1810. Paris, Oneida County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 May 2025.

“Latham Household.” Federal Census, 1820. Paris, Oneida County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 May 2025.

“Latham Household.” Federal Census, 1830. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 May 2025.

“Latham Household.” Federal Census, 1840. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 May 2025.

“Latham Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 May 2025.

Lester, Frederick W. “The Latham Family.” Centennial Volume of Papers of the Seneca Falls Historical Society. Seneca Falls Historical Society, 1948. pp. 171-179.

“Obadiah Latham.” Findagrave.com, Accessed May 25, 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/272964278/obadiah_b-latham.

“Obadiah Latham.” War of 1812, Payroll Abstracts, New York State Militia, 1812-1815. Ancestry.com, Accessed May 25, 2025.

Report of the Woman's Rights Convention, Held at Seneca Falls, N.Y., July 19th and 20th, 1848. John Dick, 1848.

Shaw, David. "One to Save: Original Trinity Church Makes Landmark Society's 'Five to Revive' List." Finger Lakes Times, Accessed May 25, 2025. https://www.fltimes.com/news/one-to-save-original-trinity-church-makes-landmark-society-s-five-to-revive-list/article_96905ee4-52e4-11e4-97c7-e7babbba407c.html.

“Susan B. Anthony’s Headstone Gets Plastic Shield for Voter Sticker.” PBS.org, Accessed May 25, 2025. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/susan-b-anthonys-headstone-gets-shield-from-voter-stickers.

Wellman, Judith, & Tanya Warren. Discovering the Underground Railroad, Abolitionism and African American Life in Seneca County, New York, 1820-1880. Seneca County, 2006.

“The Woman Voter.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 15 July 1923, p. 14A.

“Women Drafting Equal Rights Plans.” New York Evening Post, 21 July 1923, p. 3.