Signer #89, Jonathan Metcalf, "The Departed"

Jonathan Metcalf

Born: circa 1791, Barre, Massachusetts

Died: December 25, 1861, Brownstown, Wayne County, Michigan, age 70

Occupations: Teacher, Farmer, Coroner, County Supervisor, Justice of the Peace, Inspector, Tax Assessor, Constable

Local Residence: Gravel Road, Seneca Falls

A clue to the identity of Signer #89 popped up during the search for Joel Bunker (#94). An entry for Jonathan Metcalf’s household appears immediately after Bunker's in the 1840 census. Yet, Jonathan Metcalf is missing without a trace from the all-important 1850 census. In cases like this one, his absence entails one of four possibilities: he either died, changed his name, went uncounted in 1850, or left town. Evidence led me to the last of these four alternatives.

A number of sources, including Judith Wellman and Tanya Warren, ultimately place Signer #89 in Wayne County, Michigan (116). Jonathan Metcalf had already relocated and established a farm in Brownstown, Michigan, just two summers after the Seneca Falls Convention. This means he beat a hasty retreat from New York State after living there for more than four decades. Other signers who migrated to Michigan include Joel Bunker, Catharine Fish Stebbins (#11), Stephen E. Woodworth (#91), and Isaac Van Tassel (#95). It is easy to imagine the last 11 male signers of the Declaration chatting during the Convention about their big future plans for a farm in the Wolverine State.

Investigation into Jonathan Metcalf’s life in Seneca Falls reveals that he was deepily invested in the early activisms taking shape there. He was an ardent supporter of temperance, occupied a leadership position in Seneca Falls’ first anti-slavery society, and defended the right of at least one woman to speak her mind publicly. Jonathan’s biography also suggests that he was obsessed with finding a denominational church that was compatible with his increasingly progressive worldview. In this pursuit, Jonathan and his brother Joseph were instrumental in organizing no fewer than three of the village’s Protestant churches. In spite of all the "good trouble" he stirred up, Jonathan Metcalf decamped from Seneca Falls just as his causes were gaining momentum locally. In creating this profile, I searched for some explanation as to why he might have left town at such a critical moment. His story uncovered a number of salient connections to other signers of the Declaration of Sentiments.

Seneca Falls’ Spring Brook Cemetery, also known as Metcalf Cemetery, contains several records regarding the extended Metcalf family. According to cemetery records, Jonathan Metcalf was born in Barre, Massachusetts, around 1791. His parents were Sybil Broad and John Metcalf. John was a veteran of the Revolutionary War who served in the Continental Army during the opening years of the conflict (Massachusetts 706). At some point after 1806, the Metcalfs and their 11 children relocated to the Finger Lakes Region. John Metcalf died in March 1814, and Jonathan was appointed as executor of his father’s estate (Wellman and Warren 678).

Jonathan spent the earliest part of his adulthood as a teacher, serving as an instructor in the village's first school. As a schoolmaster in Seneca Falls, Jonathan was succeeded by Anson Jones. The History of Seneca County (1876) reports that Jones went on to serve as the “governor” of Texas (106). Jones was, in fact, a prominent Republic of Texas politician and the short-lived nation’s very last president.

His career as an educator might also have kept Jonathan Metcalf out of the War of 1812—at least, for a little while. An often-repeated anecdote about Jonathan suggests that teaching allowed him to stay in the village and court the woman who eventually became his wife. In his early 20s, Jonathan developed a crush on Betsey Miller, the daughter of a local tavern keeper and minister. In 1903, Harrison Chamberlain shares the details of the courtship, “Pretty Betsey Miller’s fame had gone abroad, and hither came many, especially the young, inquiring for Miller’s tavern, in order that they might pay their respects to this beautiful young lady. But just over the street, teaching in the little log school house was one far more interested than these transient comers and goers. He was a suitor, and the people were in the habit of joking Jonathan Metcalf by saying that he had turned pedagogue to avoid the draft and remain at home to court the pretty daughter of the Deacon landlord” (“Taverns”). An alternate version of this same story appears in village directories and in The History of Seneca County, which regards the anecdote as “jocosely reported." Jonathan opted to teach in order "to obtain exemption from a draft, which would have interfered with his paying court to Betsey Miller, whom he afterwards married” (106). Harrison Chamberlain also relates that Miller’s Tavern remained open until 1837 and afterwards become the site of the Wesleyan Chapel (“Taverns”). Records suggest that Jonathan and Betsey were married at some point before 1816, and the couple eventually came to occupy a home on Gravel Road, north of Seneca Falls. The structure was still standing as of 2018 (Wellman and Warren 115; Porter, "Looking").

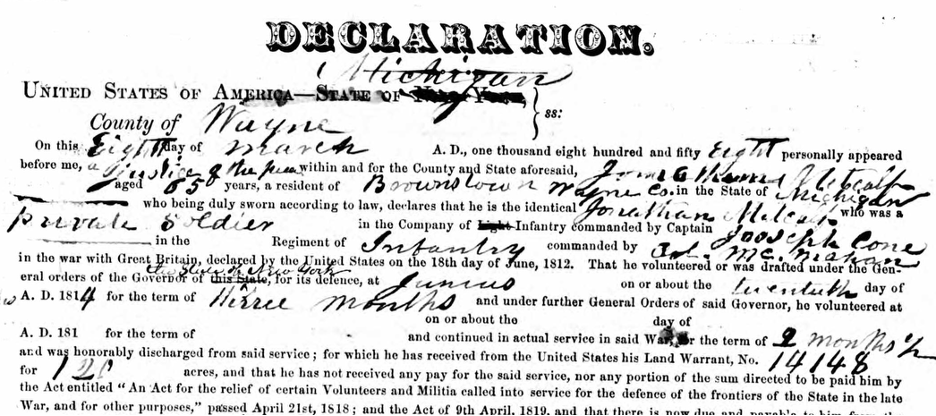

If Jonathan Metcalf used public service to avoid the war, it did not last indefinitely. An 1858 application, petitioning for belated compensation for the War of 1812, was filed by one Jonathan Metcalf, then living in Brownstown, Michigan. The affidavit states that Jonathan volunteered or was drafted at Junius in 1814 as a “private soldier.” He served under the command of Captain Joseph Cone and Lieutenant Colonel John McMahon for a period of three months. It asks for a reimbursement of $57.75 plus an additional $75 for his incidental expenditures. The document also notes that he had previously been awarded 120 acres in the West for his service. This could possibly be the same parcel of land in Michigan that became his farm.

The form was initially intended for residents of New York, but “New York” has been scratched off, with "Michigan" penciled in. Markers at Jonathan Metcalf’s gravesite also designate him as a veteran of the conflict, attached specifically to McMahon’s Regiment in the New York Militia (“Jonathan Metcalf”).

The 1820s saw Jonathan’s entrance into politics. In 1828, Jonathan acted as delegate representing Seneca County at the Republican State Convention, held at the Herkimer Courthouse (“Republican”). That same month, he was part of a nominating committee responsible for selecting a candidate for state senate (“Senatorial”). He served again in the same capacity for the 1830 election cycle (“Convention”). He also sought low-level public offices for himself. As Glenn Altschuler and Jan Saltzgaber observe, Jonathan was elected or appointed as “constable, justice of the peace, town clerk, inspector of elections, supervisor, coroner, inspector of schools, tax assessor” at one time or another (19). He was also seated as a member of the Seneca County Board of Supervisors in 1830 and 1832 (Proceedings 5). Jonathan also campaigned for Justice of the Peace in 1839 (17).

In the 1830 census, Jonathan and Betsey appear living with two male children under the age of 10 and two female children under the age of 15. As inferred from subsequent records, of these, Sophia was born around 1816, and Orton was born around 1822.

Jonathan Metcalf would later be remembered as a founder of the Seneca Falls Academy, later known as the Mynderse Academy and, later still, as Seneca Falls High School. The school was established in May 1832, with Jonathan designated as a stockholder and as inaugural board chair. He fulfilled his responsibilities, no doubt, drawing from his experience as a former teacher, and he served alongside Charles Hoskins (#85), the board secretary. A 1933 centennial celebration remembers Metcalf and Hoskins among the institution’s founding trustees. It also recalls that Orin Root, the father of Elihu Root, a future secretary of state, acted as the school’s principal in 1845 (“Centenary”).

The 1830s also saw Jonathan Metcalf delving into the partisan politics of the era. He gets a bizarre mention in an Auburn Free Press article from October 1832. The blurb touts his party credentials as a Jacksonian populist, someone who is opposed to the covert dealings of secret societies. Written by an anonymous “Anti-Mason,” it cautions readers: “BE NOT DECEIVED! The Adams men with a view to prevent the election” of Jackson's ticket, “have had the baseness to represent that they have been got up by Masonic influence; it is FALSE.” Jonathan is named as one “known to be opposed to secret societies,” whose character “should be sufficient to put down all falsehoods which may be circulated,” especially regarding any hidden Masonic influence (“Anti-Masonic”).

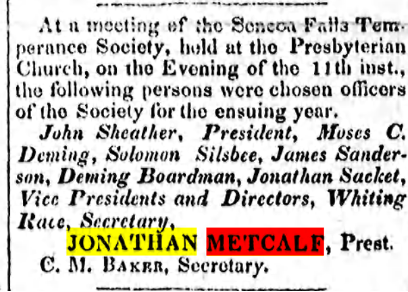

By 1836, The Seneca Farmer lists Jonathan as part of an executive committee, providing local support for the presidential candidacy of William Henry Harrison. Harrison is lauded as a “patriot, who in a gloomy period of our national affairs, periled his life for his country” (“County”). Jonathan was also an early leader of the local Temperance movement. A brief December 1836 report from the Seneca Falls Temperance Society names Jonathan as its newly elected president (“Temperance”). Whiting Race, the spouse of Rebecca Race (#54), is the organization's new secretary.

This was not the only common tie between the Races and the Metcalfs. In February 1836, Jonathan’s daughter Sophia Fanny, then 18, was claimed by the scarlet fever outbreak that swept through Seneca Falls. In less than one week's time, three of Whiting and Rebecca Race’s young children contracted the illness, died, and were buried in the same grave. The New York Evening Post focuses on the deaths of the Race children, Emmeline, Marsden, and Catharine. They “were all attacked on day, and were all the same time buried in one grave in seven days afterwards. It was an affecting scene—just one half of a family of six children entombed at one burial—one boy and two girls—and one boy and two girls spared to their afflicted parents” (“Died”). Shocking even by the high childhood mortality rates of the day, news of the deaths was also picked up by Washington’s National Intelligencer (“Died”). Their deaths suggest that Sophia might have had some personal connection with the Metcalf children, potentially as a teacher or caregiver.

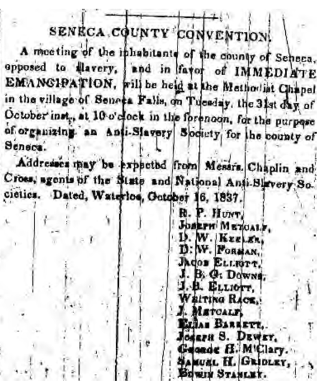

The loss of his daughter seems to have galvanized, rather than dampened, Jonathan Metcalf’s zeal for activism. An artifact uncovered by Tanya Warren and Judith Wellman shows that Jonathan was elected as vice president of a nascent antislavery society that formed in October 1837. Azaliah Schooley (#100) served as a vice president (16). This Abolitionist organization was one of the region’s first. A meeting notice for an upcoming gathering at the Methodist Church names Jonathan, his brother Joseph Metcalf, Whiting Race, and Richard P. Hunt (#69) as stakeholders. By 1840, Jonathan had ascended to the presidency of the Seneca Falls Abolitionist Society (Altschuler & Saltzgaber 85).

For the 1840 census, Jonathan Metcalf resides with a male in his 20s, possibly Orton, a female in her 30s, likely Betsey, one female child under 5 years, and one female adolescent. Along with Joel Bunker, Moses Tewksbury also appears as a head of household on the same page. Moses is the inferred spouse of Betsey Tewksbury (#47).

In the span of 15 years, from 1828 to 1843, brothers Jonathan and Joseph Metcalf were involved in the establishment of no fewer than three of Seneca Falls' Protestant churches. According to S.M. Newland, Jonathan was designated in 1828 as one of the founding trustees for the Baptist church (72). Joseph, born in Barre in 1796, amassed a sizeable fortune by operating a brickyard directly to the north of Seneca Falls. The bricks produced by Joseph’s enterprise went toward the construction of countless area buildings (Sanderson 59). Success in business made Joseph a clear choice as charitable benefactor and person-to-be-consulted prior to the construction of any church in the area. The brothers appear to have leveraged Joseph's influence and wealth as a brick maker to ensure that the churches they attended reflected their position on the issue of Abolition.

In the span of 15 years, from 1828 to 1843, brothers Jonathan and Joseph Metcalf were involved in the establishment of no fewer than three of Seneca Falls' Protestant churches. According to S.M. Newland, Jonathan was designated in 1828 as one of the founding trustees for the Baptist church (72). Joseph, born in Barre in 1796, amassed a sizeable fortune by operating a brickyard directly to the north of Seneca Falls. The bricks produced by Joseph’s enterprise went toward the construction of countless area buildings (Sanderson 59). Success in business made Joseph a clear choice as charitable benefactor and person-to-be-consulted prior to the construction of any church in the area. The brothers appear to have leveraged Joseph's influence and wealth as a brick maker to ensure that the churches they attended reflected their position on the issue of Abolition.

In 1829, Joseph became a major donor and founding trustee of the Methodist Episcopal Church, alongside future Convention participant Ansel Bascom. Joseph also oversaw the construction process for the edifice (Golder 2). According to one eyewitness, "Bro. Joseph Metcalf gave one thousand dollars towards its erection on condition that the seats should always remain free," which is to say that he stipulated that the church could not raise funds by charging congregants for pew spaces (Pegler 412).

As they became increasingly involved in the Anti-Slavery Movement, the Metcalf brothers became more disenchanted with their churches’ reluctance to formally adopt policies that condemned chattel slavery. All indications suggest that they felt a burgeoning resentment toward any effort by church leadership to suppress parishioners who wished to speak out against slavery. The story of how Joseph Metcalf was won over to the fight for emancipation survives. As related by Reverend George Pegler, the pastor eventually secured for the Wesleyan Chapel, Joseph was at one time sick with dyspepsia—an amorphous term that referred to any number of forms of abdominal discomfort or indigestion. Laid up and unoccupied with a sour stomach, Joseph happened to read Zion’s Watchman, an antislavery periodical. The consequences of this bout of dyspepsia were profound. For Pegler, it marked the beginning of “the antislavery movement in the Methodist Episcopal Church in Seneca Falls,” which Pegler concludes was “evidently providential” (409). In autumn 1835, Joseph would be in attendance at the first meeting of the New York State Anti-Slavery Society, held in Utica and Peterboro. He was then a driving force behind the adoption of an 1838 anti-slavery resolution at the Methodist Church in Seneca Falls (Porter, "Looking").

While Joseph was undergoing his damascene conversion, Jonathan was deposed repeatedly in the 1843-1844 ecclesiastical trial of Rhoda Bement. As covered in the profile for Delia Mathews (#14), Bement was tried by Presbyterian church elders for a boisterous confrontation with her minister, Horace Bogue. Bement pressed Bogue on his views regarding slavery and on the failure of the Presbyterian church to denounce it. Because of Bement’s perceived insolence, Presbyterian elders deliberated, with witnesses and evidence, over whether to revoke her church membership. Jonathan Metcalf gave testimony on the matter, especially in reference to a lecture given by traveling Abolitionist Abby Kelley.

Jonathan allowed that he and Rhoda Bement were both present at a speech delivered by Kelley. When asked if he regarded the lecture as “profitable,” Jonathan responded in the affirmative and specified that Bement was seated on the dais at the event, near Kelley. When asked if Kelley asserted her anti-slavery views too aggressively in order to sway the opinion of her audience, Jonathan allowed, “On some minds it might have strengthened prejudices, on others might have moved conviction” (quoted in Altschuler & Saltzgaber 113). But the tone of Kelley's rhetoric was unequivocal. Jonathan stated under oath that Kelley regarded complicit churches as “guilty of slaveholding,” and those institutions “were not Christian if they practiced these things, viz. sold men, women & children” (quoted in Altschuler & Saltzgaber 114). Jonathan also testified that he was well aware of the consequences of signing one's name to an anti-slavery pledge, circulated by Kelley. The church leadership had made it clear to their flocks that anyone who signed such a document should expect to be excommunicated. Jonathan’s testimony reverberates with an unspoken contempt for the proceedings, especially as a non-Presbyterian. Bement's trial was clearly intended to silence the Abolitionist polemics of Bement and other women like her.

As Jonathan and Joseph Metcalf drifted away from the churches they helped to found, Joseph played an important role in the creation of a Wesleyan Methodist church in Seneca Falls, the Wesleyan Chapel. Wesleyan Methodism, in opposition to orthodox Episcopal Methodism, was openly and explicitly opposed to human bondage. In records first uncovered by Sharon Brown, Joseph Metcalf wrote to The True Wesleyan twice in 1843, announcing the formation of a new church at Seneca Falls. Dated January 3, 1843, Joseph’s first letter attests, “there are quite a number here who have withdrawn their fellowship and support from a slave-holding and slavery-defending church, and are waiting the opening of providence on their behalf.” In the closing, Joseph writes, “I remain yours for God and the oppressed” (“Seneca”). A second letter from the following February, entitled "Withdrawal at Seneca Falls," claims that 26 church-goers have divested from their respective churches in favor of the new congregation and church. “We are now negotiating for a lot, and shall commence in the spring to build a house of worship—can obtain a house sufficiently large, in which to hold meetings until our church is built,” he states (“Withdrawal”). Joseph Metcalf's exodus from the local Episcopal Methodist church meant that it began charging its congregants for seating.

Beyond making a monetary donation for the Wesleyan Chapel’s construction, Joseph served as one of the church’s initial trustees. Prior to completion of the edifice, the initial Wesleyan services were held at the Seneca Falls Academy, the school that Jonathan Metcalf helped to found (Manual 171). Joseph also obtained an insurance policy for the edifice by April 1850 (Brown 6). The Metcalf brothers were initially attached to separate Christian denominations, one Baptist and one Methodist. Their shared animoisty toward chattel slavery compelled them, in time, to build a new church. The Wesleyan Chapel subsequently proved to be a hotbed of anti-slavery activism.

In spite of such exciting developments, the 1840s were hard years for Jonathan Metcalf. An incomplete burial record for Jonathan’s spouse, Betsey Miller Metcalf, signals that she passed away some time in the 1840s. A marker at Spring Brook Cemetery is said to bear the following inscription: “Here sleep in the long and dark of death, the cold remains of Elizabeth, my wife and six of our children and three of our grandchildren” (“Elizabeth Metcalf”). In November 1847, Jonathan lost an election for county clerk to Isaac Fuller, a newspaper editor and the future enumerator of the 1850 census. Jonathan received 55 votes; Fuller carried the day with 1,988 (“Board”). In nearby Lodi, Jonathan’s mother Sybil Broad Metcalf died in June 1848, only one month prior to the Convention. She is listed as among those interred at Spring Brook Cemetery (“Sybil Metcalf-Marsh”).

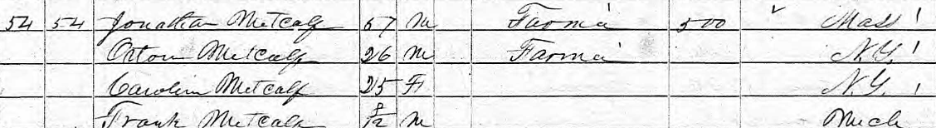

These downturns seem to have set the stage for Jonathan’s abrupt departure for Michigan. In a July 1850 census entry, Jonathan Metcalf resides in Brownstown, a township about 20 miles south of Detroit's city center. Jonathan is 57 and just starting out as a farmer. His estate is valued at $500, and he resides with son Orton, 26, and Orton’s wife, Caroline, 25. Caroline and Orton now have a baby named Frank, an 8-month-old born in Michigan. Frank's nativity and age indicate that the Metcalfs had arrived in the Midwest some time in 1849, if not earlier.

According to the 1850 census population schedule, the Metcalf farm is already up and running with a horse, 3 cows, 15 sheep, and 3 pigs. Wheat, corn, and oats are being grown there.

Jonathan’s relocation may have been in the offing for over a decade. An 1837 General Land Office document, approved by President Martin Van Buren, deeds a tract of land in Michigan to “Jonathan Metcalf of Seneca County, New York.”

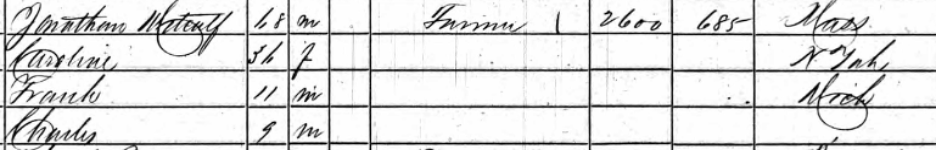

According to his epitaph, Jonathan’s son Orton Metcalf died on August 11, 1852, at age 30 ("Orton Metcalf"). In the 1860 census for Brownstown, Jonathan labors as a farmer. He lives with his son's widow, Caroline, 36, and two male grandchildren, Frank, 11, and Charles, 9.

The Metcalf farm is valued at just over $3,200. According to the population schedule for 1860, the farm sat on 77 acres. Tt had 3 pigs, 4 milk cows, and 3 horses, and corn, rye, and wheat are being farmed.

Signer #89 died in his 70th year on Christmas Day, 1861. He is buried in Oak Forest Cemetery in Wayne County, Michigan (“Jonathan Metcalf”).

In August 1852, Frederick Douglass' Paper names Jonathan’s brother Joseph Metcalf as a delegate of the Seneca Falls Liberty Party, slated to attend an upcoming convention. The local chapter of the Liberty Party convened in the Wesleyan Chapel and passed a set of resolutions, the first declaring that “natural rights are co-extensive with man’s earthly being” and are “far more sacred than any civil enactment” (“Proceedings”). That autumn, Frederick Douglass' Paper essentially offers its endorsement, reporting that Joseph Metcalf has been nominated for sheriff of Seneca County by the Free Democracy Party (“Free”).

Even after the Civil War resolved the issue of slavery, sectarian hostilities still lingered in Seneca Falls. On one occasion, it meant real violence for Joseph Metcalf. George Pegler recalls in 1879 that he found Joseph Metcalf so trustworthy to the point that his “advice and example seemed safe for me to follow in every particular excepting his connecting himself with a secret temperance society, and his sympathy with the Second Adventists, in both of which I hope he now sees his error” (412). Trouble eventually came looking for Joseph in the form of William Lyle, a minister who assumed the pulpit of the First Wesleyan Methodist Church in 1865. In terms of his political orientation, Lyle was pro-temperance and in favor of secret societies, views that should have aligned neatly with Joseph’s (Manual 171). For whatever reason, Lyle eventually attempted to reconcile the Seneca Falls Wesleyans with the main branch of the Methodist Episcopal Church. When this effort failed, Lyle then attempted to re-affiliate the Wesleyan church as Congregationalist.

Joseph Metcalf appears to have objected publicly to the new alignment proposed by Lyle. Tensions finally came to a head on September 9, 1869, when group of Lyle’s supporters stormed a church meeting and threw the interim pastor out into the street. Joseph Metcalf, then 73, got "dragged from his knees while praying” and was then “kicked and stamped on" by Lyle’s supporters (quoted in Brown 19).

Joseph died in March 1880, aged 83 (“Joseph Metcalf”). An obituary remembers Joseph Metcalf’s contribution to the construction of the Wesleyan Chapel. He was “foremost in erecting the present church edifice of that denomination.” Joseph, like Jonathan, “was a radical on the subject of temperance.” But, after Jonathan left town, Joseph “took a prominent part...in the controversy, which led to the organization of the Congregational church.” The obit also reports that Joseph returned to the Methodist Episcopal Church by the end of his life (“Obituary”). Simmering interdenominational dissensions did not bode well for the Wesleyan Chapel itself. By 1903, Harrison Chamberlain observes that the site of the Seneca Falls Convention, built by Joseph Metcalf, no longer served as a place of worship. It had been “converted into the Johnson Opera House and [is] now used for manufacturing” (“Tavern”).

The Metcalf brothers were able to exert a unique form of influence during the antebellum period. They could use the power of their purse and their social standing to establish churches that embodied their personal worldview, primarily in the domains of slavery, temperance, and women's rights. Still, their church-centered activism was not without its dangers. The instance of actual violence experienced by an elderly Joseph Metcalf might help to explain why Jonathan Metcalf was willing to leave New York State decades earlier. Signer #89 got out of town just as the Abolition Movement, the Temperance Movement, and the Women's Rights Movement were starting to gain steam. Prior to this, Jonathan Metcalf played an important role in the intertwined ecclesiastical and activist histories of Seneca Falls. In the end, maybe Michigan was so tempting because it was thoroughly removed from the gathering storm in the East.

Works Cited

Altschuler, Glenn C., and Jan M. Saltzgaber. Revivalism, Social Conscience, and Community in the Burned-over District: The Trial of Rhoda Bement. Cornell University Press, 1983.

“Anti-Masonic Jackson Ticket.” The Auburn Free Press, 10 Oct. 1832, p. 1.

“The Board of County Canvassers.” The Seneca Observer, 25 Nov. 1847.

Brown, Sharon A. Historic Structure Report: Historical Data Section, Wesleyan Chapel, Women’s Rights National Historical Park, New York. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1987.

"Centenary of Seneca Falls High School Recalls Early History.” The Rochester Democrat, 14 May 1933, p. 5A.

Chamberlain, Harrison. “Early Taverns of Seneca Falls.” Seneca County Courier-Journal. 14 May 1903, p. 1.

“Died.” The New York Evening Post, 6 Feb. 1836, p. 1.

“Died.” The Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.), 20 Feb. 1836, p. 3.

“Elizabeth Miller Metcalf.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 4 Dec. 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/149068487/elizabeth-metcalf.

“Free Democracy of Seneca County.” Frederick Douglass’ Paper, 5 Nov. 1852, p. 1.

Golder, A.W. “Record of the Methodist Episcopal Church.” 100th Anniversary of the Town of Junius. Seneca Falls Historical Society, 1903, pp. 1-5.

History of Seneca Co., New York. Everts, Ensign & Everts, 1876.

“John Metcalf.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 4 Dec. 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/32556768/john-metcalf.

“Jonathan Metcalf—Application of Claim, 1858.” New York, War of 1812 Certificates and Applications of Claim and Related Records, 1858-1869. Ancestry.com, Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

“Jonathan Metcalf—Land Grant.” U.S., General Land Office Records, 1776-2015. Ancestry.com, Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

“Jonathan Metcalf.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 4 Dec. 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/10606084/jonathan-metcalf.

“Joseph Metcalf.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 4 Dec. 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/149034323/joseph-metcalf.

Manual of the Churches of Seneca County with Sketches of Their Pastors. Courier, 1896.

Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War. Vol. X. Wright & Potter, 1902.

“Metcalf Household.” Federal Census, 1830. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

“Metcalf Household.” Federal Census, 1840. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

“Metcalf Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Brownstown, Wayne County, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

“Metcalf Household” Federal Census Non-population Schedules, 1850. Brownstown, Wayne County, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 Nov. 2025.

“Metcalf Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Brownstown, Wayne County, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

“Metcalf Household” Federal Census Non-population Schedules, 1860. Brownstown, Wayne County, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 Nov. 2025.

Metcalf, Joseph. “Withdrawal at Seneca Falls.” The True Wesleyan, 4 Mar. 1843, p. 4.

---. “Seneca Falls, N.Y., Jan 3. 1843.” The True Wesleyan, 28 Jan. 1843, p. 1.

Newland, S.M. “The First Baptist Church.” 100th Anniversary of the Town of Junius. Seneca Falls Historical Society, 1903, pp. 72-80.

“Obituary.” Seneca County Courier, 26 Mar. 1880, p. 4.

“Orton Metcalf.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 4 Dec. 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/10606090/orton_m-metcalf.

Pegler, George. The Autobiography of the Life and Times of the Rev. George Pegler. Wesleyan Publishing House, 1879.

Porter, Susan Clark. "Looking Back: SF Church's Anti-Slavery History." Finger Lakes Times, 19 Aug. 2018. https://www.fltimes.com/lifestyle/looking-back-sf-churchs-anti-slavery-history/article_09fb2567-9db7-5478-a5aa-b262101c2c92.html.

“Proceedings of the Liberty Party Convention of Seneca County.” Frederick Douglass' Paper, 27 Aug. 1852, p. 3.

“Republican Senatorial Convention.” The Geneva Gazette, 27 Oct. 1830, p. 2.

“Republican Senatorial Nomination.” The Geneva Gazette, 8 Oct. 1828, p. 1.

“Republican State Convention.” Delaware Gazette, 1 Oct. 1828, p. 1.

Sanderson, James. “Some Early Recollections of Seneca Falls.” 100th Anniversary of the Town of Junius. Seneca Falls Historical Society, 1903, pp. 58-59.

Seneca County Board of Supervisors. Proceedings of the Board of Supervisors for the Year 1917. Connell, 1917.

“Seneca County Convention.” The Seneca Farmer, 18 May 1836, p. 1.

“Sybil Marsh Metcalf.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/149035444/sybil-metcalf_marsh.

“Temperance Cause.” Seneca Farmer, 31 Dec. 1834, p. 1.

Vital Records of Barre, Massachusetts. Rice, 1903.

Wellman, Judith, & Tanya Warren. Discovering the Underground Railroad, Abolitionism and African American Life in Seneca County, New York, 1820-1880. Seneca County, 2006.