Signer #94, Joel Bunker: “The Pioneer”

Signer #94: Joel Bunker (also Bonker and Bouker)

Born: 1812, Saratoga County, New York State

Died: 1888, Grass Lake, Jackson County, Michigan, age 75-76

Occupations: Lockkeeper, cooper, house painter, wagon-maker, wagon-repairer

Local Residence: 10 Miller Street, Seneca Falls

Thanks to Alyssa Eveland for assistance provided in the production of this piece.

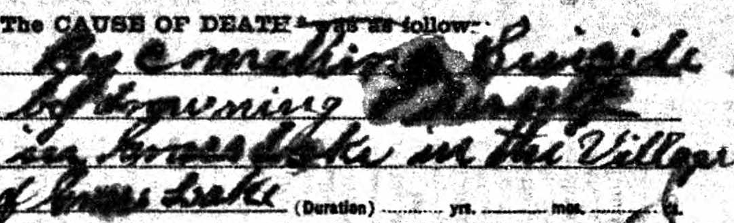

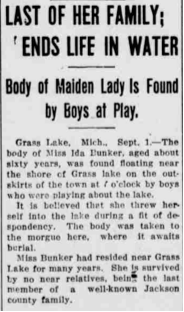

On September 1st, 1914, a group of boys playing by a local lake stumbled upon a body, submerged in the water. This drowning occurred at Grass Lake, Michigan, a little township situated to the west of Ann Arbor. The corpse was that of Ms. Ida Bunker, aged 60, who had apparently taken her own life. The cause set down on her death certificate claims that she perished “by committing Suicide by drowning herself in Grass Lake in the Village of Grass Lake.” The date of her suicide is speculated to be August 29th, which suggests that her remains had been in the water for approximately three days before being recovered.

As for a motive, “it is believed that she threw herself into the lake during a fit of despondency,” The Owosso Times reports. A detail that compounds the tragic loss of the "Maiden Lady" is that she was the last of her family line in the area. The Times relates that Ida Bunker “is survived by no near relatives, being the last member of a well-known Jackson county family” (“Last”).

Ida Bunker was, in fact, the last-living child of Signer #94, Joel Bunker, who completed the 500-mile trek from Seneca Falls to Michigan at some point in the 1860s.

The reason why Joel Bunker relocated his family to this particular spot is abundantly clear. Grass Lake had been settled and established by other members of the Bunker family three decades earlier. Signer # 94's life story reveals how family ties often dictated the routes taken by the pioneers who traversed the continent during the 19th century.

One remarkable archival feature of Joel Bunker's life in Michigan is that searches uncovered death records for the entirety of his immediate family, excluding Joel himself. These documents afford an opportunity to determine what forces were responsible for the high death rate of settlers during Manifest Destiny. Were pioneers killed by disease? Were conflicts with other settlers or indigenous people to blame? The story of the Bunker family provides one example that might help to address the broader question.

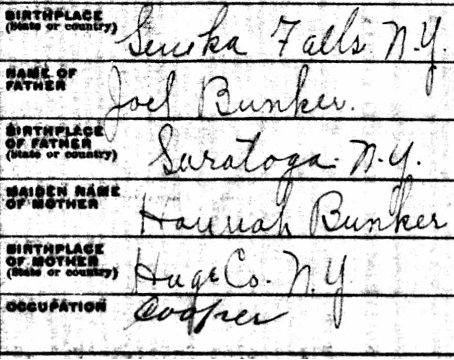

A descendant of German immigrants, Joel Bunker was born in Saratoga County, New York, around 1812. Some time before 1833, he married Hannah, the daughter of Oliver and Hannah Bunker or Bonker. Most likely a cousin to Joel, Hannah was born in January 1813 and might have been a native of Cayuga County. The death certificate of her son Martin identifies Hannah's birthplace as “Hage County, New York”—“Hage” possibly being an errant transcription of “Cayuga.” The burial location of Hannah’s father is additionally thought to be part of a Bunker family plot in Montezuma, Cayuga County (“Oliver Bonker”). Hannah and Joel had their first child, Mary, in December 1833. A son, named Martin, was born in July 1836 at Seneca Falls, which suggests the Bunkers had moved there by that time. Hannah Maria, later known as Ida, was born in May 1841.

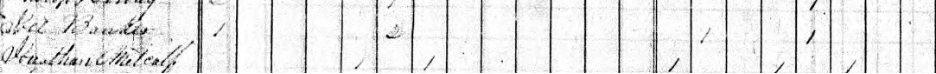

According to Judith Wellman, Joel Bunker worked as a lock-tender on the Seneca Canal during his early years in Seneca Falls (130). “Joel Banker” is listed in the 1840 census as head of household. He lives with another male in his 30s, a female in her 20s (probably Hannah), and two children under age 10. His household listing appears immediately before Johnathan Metcalf, a likely candidate for Signer #89.

An 1843 report on the outcome of local elections indicates that a “Joel Bonker” received one vote for assemblyman in Seneca Falls (“Canvass”). Joel appears to have spelled his surname interchangeably as “Bonker,” “Bunker,” or “Bouker” during this period. Variant spellings of one's name were a common practice in the first half of the 19th century.

According to Judith Wellman and Tanya Warren, Joel was a founding member of the Methodist congregation at the Wesleyan Chapel. He donated money toward the construction of the edifice in 1843 (130, 145). At the Seneca Falls Convention, Joel Bunker joined Henry Seymour (#75), Robert Smalldridge (#83), Isaac Van Tassel (#95), E.W. Capron (#96), and the best candidate for Jacob Matthews (#84) as married male signatories whose spouses did not sign the document.

The Bunkers, their surname given as “Bonker,” appear in the 1850 census for Seneca Falls. They are listed on the page immediately preceding the households of Eunice Newton Foote (#5), Elisha Foote (#72), and Henry Seymour (#75).

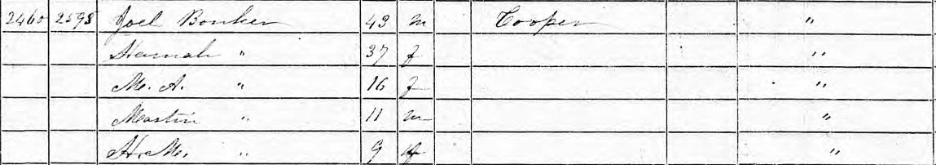

Joel is now 43, and he works as a cooper. Hannah is 37. Their children Mary ("M.A."), Martin, and Hannah Maria ("H.M") range in age from 9 to 16. Joel and Hannah would welcome their four child, Bradford, in 1851.

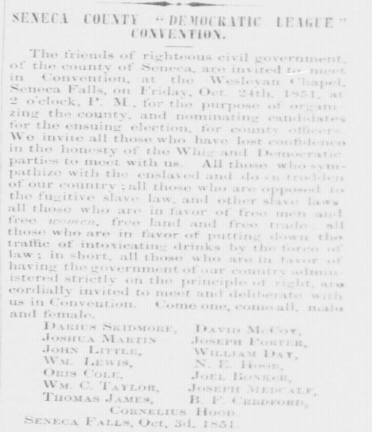

Beyond the Convention, Joel Bunker became involved in other progressive causes while residing in Seneca Falls. In an artifact first recovered by Wellman and Warren, Joel's name appears as part of an invitation to the newly formed Seneca County Democratic League. The organization was to have an open meeting at the Wesleyan Chapel on Friday, October 24, 1851. An advertisement placed in Frederick Douglass’ Paper outlines its political platform: “We invite all those who have lost confidence in the honesty of the Whig and Democratic parties to meet with us. All those who sympathize with the enslaved and downtrodden of our county, all those who are opposed to the fugitive slave law, and other slave laws…all those who are in favor of free men and free women, free land and free trade…all those who are in favor of putting down the traffic of intoxicating drinks by the force of law; in short, all those who are in favor of having the government of our country administered strictly on the principle of right are cordially invited to meet and deliberate with us in Convention. Come one, come all, male and female.” The group's orientation on abolition, temperance, and women’s rights are patently self-evident in this statement—especially through its emphatic italicization of “free women.” It is important to recognize the obvious similarities between this act of political caucusing and the Seneca Falls Convention.

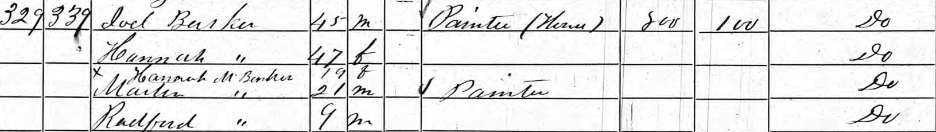

In 1860, the “Barkers” live in the 2nd Ward of Seneca Falls.

Hannah is listed inaccurately as 47. Joel, 45, is a “Painter (House)” with an estate valued at $1,800 dollars. Martin, now 21, has entered the same profession as his father. Daughter Hannah, 19, was not entered correctly in the ledger, and her information has been inserted marginally. Bradford, here given as “Radford,” is 9 years old. In a solidly blue-collar neighborhood, the Bunkers live alongside brickmakers, carpenters, and day laborers.

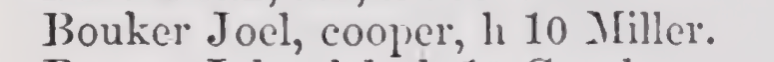

In Delancey Brigham’s 1862 directory for Seneca County, “Joel Bouker” appears as a cooper with a home at 10 Miller Street (37). This location is literally steps away from the Wesleyan Chapel, just around the corner of Miller and Clinton Street. His proximity makes Joel Bunker the signer who lived closest to the site of the Convention.

As Wellman and Warren first noticed, one Joshua Martin also boards at 10 Miller Street in the 1862 directory (56). A laborer and Free Soil activist, Martin is said to have co-owned the property with Joel Bunker (144-5). Alongside Joel, Martin's name appears in the Seneca County Democratic League’s 1851 open call.

The 1881 History of Jackson County, Michigan offers some insight into the whereabouts of Joel and Hannah’s eldest child, Mary, who has disappeared from the Bunker household by the 1860 census. In 1853, “Miss Mary Bunker, of Seneca county, N.Y.” wed George Bunker of Grass Lake, Michigan. Mary is “a lady one year his [George's] senior.” Like Joel, George Bunker was born in Saratoga County but migrated to Grass Lake as a child in 1836. The History of Jackson County adds that George returned to Grass Lake in 1870, suggesting that he resided in the Finger Lakes Region or elsewhere for a time before coming home (850-1). A Mary Bunker appears in the 1860 census in Seneca Falls, living in the household headed by Joel’s friend and associate Joshua Martin. The common ties to Saratoga County suggest that the Bunkers of Seneca Falls and the Bunkers of Grass Lake are related. A biographical sketch of George’s older brother, Samuel Bunker, in 1890’s Portrait and Biographical Album of Jackson County, Michigan supports this contention. Samuel's and George’s father departed “for the Michigan Territory but stopped in Cayuga County, N.Y. until May 5th, 1836” (563). Their pathways of residence and migration overlap too neatly for the Bunkers of New York and Michigan to be perfect strangers.

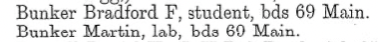

The Seneca Falls Bunkers, evidently following Mary’s lead, arrived in Grass Lake by 1867 (147). In an 1867 directory for nearby Jackson City, Bradford, a student, and Martin, a laborer, board together at 69 Main Street (139).

Besides Joel Bunker, the signers of the Declaration of Sentiments known to have relocated to Michigan include Catharine Fish Stebbins (#11), Stephen E. Woodworth (#91), and Isaac Van Tassel (#95).

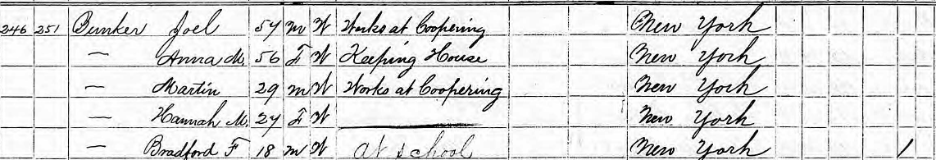

In the 1870 census for Grass Lake, Joel is 57. Hannah is 56 and “Keeping House.” Martin, 29, “works at Coopering,” following in his father’s footsteps. Bradford, 18, attends school, and no vocational entry is given for Hannah, now 24.

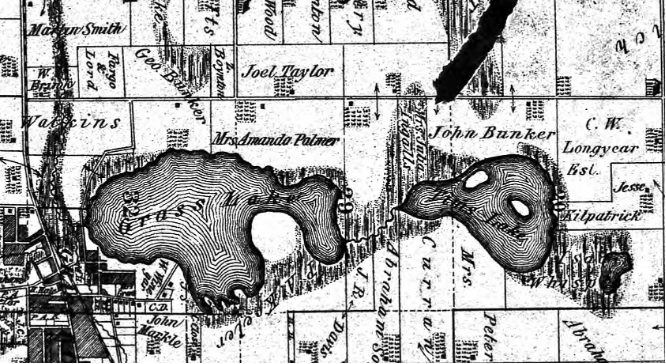

A set of 1839 land patents, signed by President Martin Van Buren, deeded land around Grass Lake to the first Bunker settlers. An 1874 map of Grass Lake contains no mention of recent émigré Joel Bunker, but it does mark off tracts of land owned by John Bunker and George Bunker.

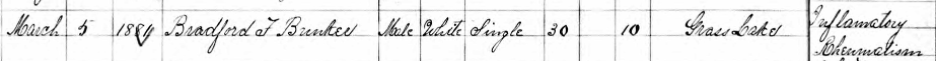

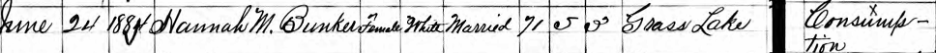

In March 1881, Bradford Bunker, son of Joel and Hannah, died at age 30 in Grass Lake.

The cause given in the Michigan Death Index is “Inflamatory Rheumatism.” In June 1884, Joel’s spouse Hannah M. Bunker died of consumption or tuberculosis at age 71.

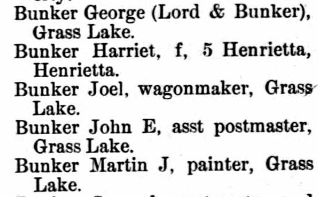

Joel is a “wagonmaker” and “wagon repairer” in 1885 and 1888 directories for Jackson County, alongside other members of the Bunker clan (356, 394). The 1885 listing also includes Joel’s son-in-law, George, and his son Martin, a painter.

Signer #94, Joel Bunker died in 1888, probably during the summer months. An article in the Jackson Daily Citizen from July 14, 1888, states that “Joel Bunker is in precarious condition owing to infirmities incident to old age. Last Tuesday night his life was despaired of and the indications are that the end is near” (“Joel Bunker”).

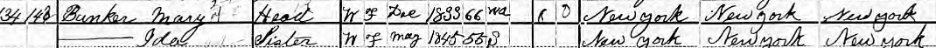

According to his death certificate, Mary’s husband George Bunker died of laryngeal phthisis, a form of tuberculosis that attacks the larynx, in May 1898. Daughters Mary and Ida (Hannah Maria) appear living together in the 1900 census for Grass Lake.

Mary, by now widowed, reports in this census that she has no surviving children.

According to his death certificate, Joel’s son Martin J. Bunker died in Grass Lake on May 22, 1904, at age 68. The cause set down on his death certificate surmises, in shorthand, that “Probably organic disease of heart” was responsible. His occupation is listed as cooper, and he never married. His sister Mary serves as the informant on the document. Martin Bunker’s death certificate is the last official document to contain any specific information pertaining to his parents’ birthplace.

With Ida serving as informant, Mary Bunker died in April 1908 from “Cancer of the small intestine.” She was 75.

The last of the family, Joel’s daughter Hannah Maria or Ida took her own life for reasons unknown in 1914. The burial places of Joel and Hannah Bunker are not known. According to various pages on Findagrave.com, a family plot, containing the graves of Mary, Martin, Bradford, and Ida, is located at Grass Lake West Cemetery. That is a likely location for their parents' unmarked graves.

Perhaps the allure of the West attracted the Bunker family to make the journey all the way to Grass Lake, Michigan. Maybe their exodus from Seneca Falls was impelled by the notion that a better life lay somewhere out on the frontier. Whatever the reason, Joel Bunker’s life indicates how extended family bonds directed migration for those who took part in America's westward expansion.

With the exception of his son Bradford, none of Joel Bunker’s family died young after migrating to Michigan. The Bunkers succumbed to diseases, primarily tuberculosis, and to other natural causes. Their deaths were most certainly not the violent shootouts you might see depicted in a Western.

By the same token, their deaths also draw attention to the common practice of familial intermarriage during this era. Did endogamy intensify for some settler families, who intermarried more frequently and intensely out West as a psychological response to the displacements and sense of rootless caused by immigration? Mary Bunker, for example, was the daughter of Joel Bunker and Hannah Bunker, who were likely cousins. Mary Bunker then married George Bunker, who was likely her cousin. Mary and George then had no surviving children. If this unspoken strategy of pioneer intermarriage actually existed, it might well have hurt families' prospects for long-term success in the West. Prolonged endogamy would lead to medical issues like infertility and chronic illness. It could have reduced immuno-response to infectious disease. Did intermarriage—not gunfights, wagon raids, or war parties—ultimately jeopardize families like the Bunkers? Maybe being the lone surviving member of her family in Grass Lake fueled the “fit of despondency” that brought about Ida Bunker's suicide in 1914. The sad final chapter of Ida Bunker's life leads one to believe that perhaps her death was brought about, in part, by loneliness.

Works Cited

“Banker Household.” Federal Census, 1840. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 15 Aug 2025.

“Barker Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 15 Aug 2025.

“Bonker Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 15 Aug 2025.

“Bradford Bunker.” Michigan Death Index, 1881. Ancestry.com, Accessed 15 Aug 2025.

“Bradford Bunker.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 15 Aug. 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/17751432/bradford-bunker.

Brigham, DeLancey. Brigham’s Geneva, Seneca Falls, and Waterloo Directory and Business Advertiser, For 1862 and 1863. 1862.

“Bunker Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Grass Lake, Jackson County, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 15 Aug 2025.

“Bunker Household.” Federal Census, 1900. Grass Lake, Jackson County, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 15 Aug 2025.

“George Bunker—Death Certificate” Michigan Department of State-Vital Statistics, 1898. Ancestry.com. Accessed 15 Aug. 2025.

“Grass Lake Township Map, 1874.” US Indexed County Land Ownership Maps. Ancestry.com. Accessed 15 Aug. 2025.

“Hannah Bunker.” Michigan Death Index, 1884. Ancestry.com, Accessed 15 Aug 2025.

“Hannah Bunker—Death Certificate” Michigan Department of State-Vital Statistics, 1914. Ancestry.com. Accessed 15 Aug. 2025.

“Hannah Maria Bunker.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 15 Aug. 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/17751424/hannah_maria-bunker.

“Hannah Mariah Bunker.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 15 Aug. 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/261725443/hannah_mariah-bunker.

History of Jackson County, Michigan. Inter-state Publishing Company, 1881.

Jackson City and County Directory for 1885-6, R.L. Polk, 1885.

“Joel Bunker—Ancestors and Kin of James Henry Decker.” GenArchives.com, Accessed 15 Aug. 2025. https://genarchives.com/deckershaw/decker/p47.htm#i2338.

“Joel Bunker.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 15 Aug. 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/261725660/joel-bunker.

“John Bunker—1839 Land Patent.” U.S. General Land Office Records.Ancestry.com. Accessed 15 Aug. 2025.

“Last of her Family; Ends Life in Water.” The Owosso Times (Michigan), 4 Sep. 1914, pg. 7.

“Martin Bunker—Death Certificate” Michigan Department of State-Vital Statistics, 1907. Ancestry.com. Accessed 15 Aug. 2025.

“Martin Bunker.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 15 Aug. 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/38081473/martin_j-bunker.

“Martin Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 15 Aug 2025.

“Mary Bunker—Death Certificate” Michigan Department of State-Vital Statistics, 1908. Ancestry.com. Accessed 15 Aug. 2025.

“Mary Bunker.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 15 Aug. 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/17751429/mary-bunker.

Michigan State Gazetteer and Business Directory, 1889. R.L. Polk, 1888.

Moran, Edward. Bunker Genealogy: Descendants of James Bunker of Dover, N.H. Vol. 2. Bunker Family Association of America, 1961.

“Oliver Bonker.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 15 Aug. 2025.https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/261724675/oliver-bonker.

Portrait and Biographical Album of Jackson County, Michigan. Chapman, 1890.

“Seneca County ‘Democratic League’ Convention.” Frederick Douglass’ Paper (Rochester, New York), 16 Oct. 1851, p. 3.

“Table of the County Canvass of Seneca County, 1843.” The Ovid Bee, 22 Nov. 1843, p. 1.

Thomas, James. Jackson City Directory and Business Advertiser, for 1867 & 1868. Carlton & Van Antwerp, 1867.

Wellman, Judith, & Tanya Warren. Discovering the Underground Railroad, Abolitionism and African American Life in Seneca County, New York, 1820-1880. Seneca County, 2006.

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman’s Rights Convention. University of Illinois Press, 2010.